- Introduction

- Theoretical Concepts

- State of the Art

- Use Case

- Proof of Concept

- Benchmark & Results

- Project's Reproducibility

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

In our modern 21st century, it is becoming increasingly hard to imagine a world without access to services in the cloud. From contacting someone through mail, to storing work-related documents on an online drive and accessing it across devices, so many services have risen since the dawn of the Internet.

As the need for both compute and electrical power in the cloud is growing, so are the infrastructures. Virtualization has been a huge push towards offering more services with less hardware. By allowing to bypass the limitations of a single operating system per machine, the cloud has become more powerful and more versatile.

However, all this power comes at a cost. While large datacenters are offering services in the cloud, they are also hungry for electric power, which is becoming a growing concern as our planet is being drained of its resources. Is it possible to imagine giving up all the services we’ve grown accustomed to? Falling back to the older, less power-hungry ways?

Fortunately, virtualization is not a dead end, and innovative solutions have risen to aid in solving the power-hunger of large virtualization infrastructures. One such solution has seen the light of day: what if, instead of virtualizing an entire operating system, you were to load an application with only the required components from the operating system? Effectively reducing the size of the virtual machine to its bare minimum resource footprint? This is where unikernels come into play.

Unikernel is a relatively new concept that was first introduced around 2013 by Anil Madhavapeddy in a paper titled “Unikernels: Library Operating Systems for the Cloud” (Madhavapeddy, et al., 2013). Unikernels are defined by the community at Unikernel.org as follows.

“Unikernels are specialized, single-address-space machine images constructed by using library operating systems.” (Unikernel, n.d.)

Specialized indicates that a unikernel holds a single application. Single-address space means that in its core, the unikernel does not have separate user and kernel address space (more on this later). Library operating systems are the core of unikernel systems. The following sections will explain these concepts in more details.

Despite their relatively young age, unikernels borrow from age-old concepts rooted in the dawn of the computer era: microkernels and library operating systems.

As opposed to monolithic kernels which contain large amounts of code in kernel space, thus making it rather large, microkernels aim at reducing the size of the kernel. By doing so, microkernels diminish the amount of code in kernel space in favor of modules executed in user space.

A second aspect that microkernels aim to solve is reliability. The basis of this notion is that the more code there is, the higher the chance of encountering bugs as well as potential security flaws in the kernel. In keeping the kernel size small, microkernels reduce the risk of bugs and flaws in the kernel, which can prove fatal to a system’s operation.

Nowadays, monolithic kernels are mostly employed to provide a single version of an operating system that can potentially execute any function required. Windows and Linux are prime examples. Since neither Microsoft nor Linus Torvalds (amongst others) know what users are going to do with the operating system, the kernel integrates as much functionalities as possible out of the box (e.g.: communicating on the network, accessing files on a hard disk, launching multiple services, etc.).

In a scenario using the microkernel approach and applying it to widely used operating systems, the operating system in question would be very small. However, each user would have to install various modules based on what they want to do, because the microkernel operating system includes the bare minimum out of the box. Any additional function requires a module that is executed in user space and interacts with the underlying microkernel.

While microkernels are not ideal for lambda users (as opposed to monolithic), they are very useful in areas where reliability is a requirement. Since modules operate in user space separate from the kernel and other modules’ user space, an issue in one module cannot impact another module.

For example, in a monolithic kernel, file management functionalities are directly integrated within the kernel. Thus, if the file management were to crash, the entire kernel could be impacted, resulting in the entire system crashing (e.g.: Microsoft’s Blue Screen of Death). If another application were to run on the same machine, this service would be affected by the crash even if it had no relation to the file management function.

In a microkernel implementation, using the same use case, to access files on the disk, the appropriate module needs to be loaded in the current microkernel operating system. The same goes for providing a service on the network, another module is required and needs to be loaded. However, if the file management module were to crash, being operated in its own user space, the kernel would not be affected, leaving the system up and running. Moreover, the network module would also be untouched, because it is executing in its own user space as well, separate from the file management module.

Library Operating System is another method of constructing an operating system where the kernel and modules required by an application run in the same address space as the application itself. As opposed to the microkernel and monolithic kernel, this implies that there is no separation between kernel and user space, and the application has direct access to the kernel level functions without requiring system calls.

The aim of the library OS is to provide enhancement by exposing low-level hardware abstractions. Unfortunately, the trade off to abstracting low-level hardware is the difficulty in supporting a large range of hardware. This means that to create a full library operating system, the kernel must be compiled with device drivers written for the specific destination hardware. This made for very poor portability of library operating systems, and at the time of conceptualization no convenient solution presented themselves to solve such issue.

Nowadays, however, virtualization already provides an abstraction of the underlying hardware by exposing virtualized hardware drivers. This allows library OS implementations to support the generic virtual driver as opposed to attempting to support various hardware. This provides the basis upon which unikernel applications can be built: by combining an already tested technology that is virtualization, with library operating systems loaded with hypervisor drivers for full portability in an orchestrated environment.

Unikernels are specialized because they comprise of a single application offering a single service. Unikernels also make use of library operating systems to minimize the kernel size by including only the functions and routines required (as opposed to microkernel which require modules to be loaded, unikernels are compiled with the required modules beforehand). As a result, unikernel applications provide small, lightweight and highly efficient virtualized applications.

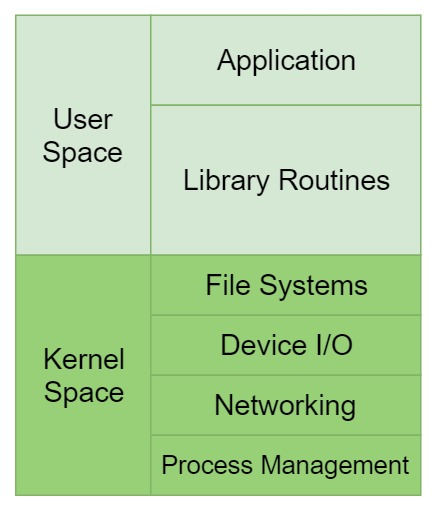

If we look at an application on a monolithic operating system, as indicated by Figure 1, we can see that for an application to run, two address spaces need to exist. A kernel space containing functions offered by the underlying operating system such as accessing I/O devices, file systems and process management. On top of the kernel space is the user space, containing the application code itself.

Figure 1 Application stack on a monolithic operating system. Source: (Pavlicek, 2017)

The application code in the user space relies on the operating system code in the kernel space to access various functions and the hardware abstracted by the operating system itself. This approach is most efficient when considering an operating system without prior knowledge of what applications are going to be run on it. Therefore, the monolithic kernel becomes bulky in its attempt to accept a wide array of applications.

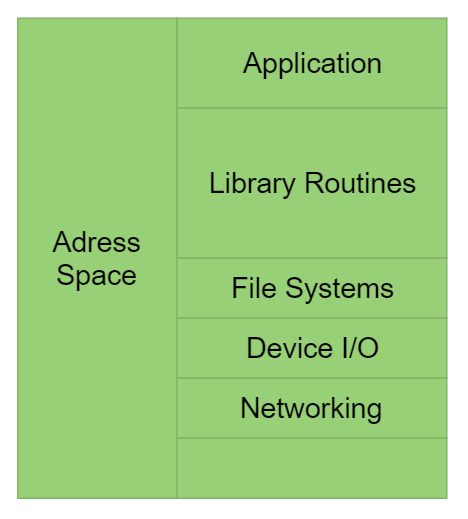

Unikernel applications, however, present a very different structure. As indicated by Figure 2, an application running in a unikernel does not present any division in its address space, which holds both the high-level application code and the lower level operating system routines.

Figure 2 Application stack on a unikernel application. Source: (Pavlicek, 2017)

To create such an application, unikernels use specialized cross-compiling (because by design, the unikernel cannot be compiled on the same system it will run) methods by selecting required low-level functions from library operating system (provided in compilable form) and cross-compiling them with the application code and configuration. The result is an image that can run as standalone to provide a service.

As mentioned previously, unikernel services present a certain advantage in contrast to virtualized and containerized services. This is due to their reduced attack surface and reduced exploitable operating system code. When offering a service over a network, both virtual machine and container solutions are packed with more tools than required by the running application. This increases the attack surface greatly.

Imagine the following scenario: a DNS name resolution service. The only purpose of such service is to capture a name resolution request, search the database and send the reply. In a virtualized or containerized case, the Linux or Windows environment providing a DNS service includes much more than just a network stack and a local database. An attack could be undertaken on the remote access functions, the user authentication mechanisms, a flawed driver, and so on. All these attacks having a common goal, accessing a command line interface to execute malicious code remotely.

Taking the same use case on a unikernel service, the library routines required are limited to accessing the network device. Even the database access can be included in the application code . In contrast to the virtual machine and container, the unikernel does not include unnecessary operating system functions such as device management, remote access, authentication mechanisms or even a command line interface.

The same DNS service is only capable of accepting DNS request and sending DNS responses. A malicious attacker cannot leverage remote access functionalities, authentication exploits or remote code execution, simply because the functions required to do so are not present in the target’s code.

1 Note: the database is not hard coded in the application code nonetheless. This is due to the way unikernel applications compile configuration and data files: on compilation time, they are linked in the code and treated as libraries in the application stack. Note that more complex infrastructures could use micro-services as opposed to hardcoding. In the case of a DNS unikernel, the database could be held in a separate unikernel.

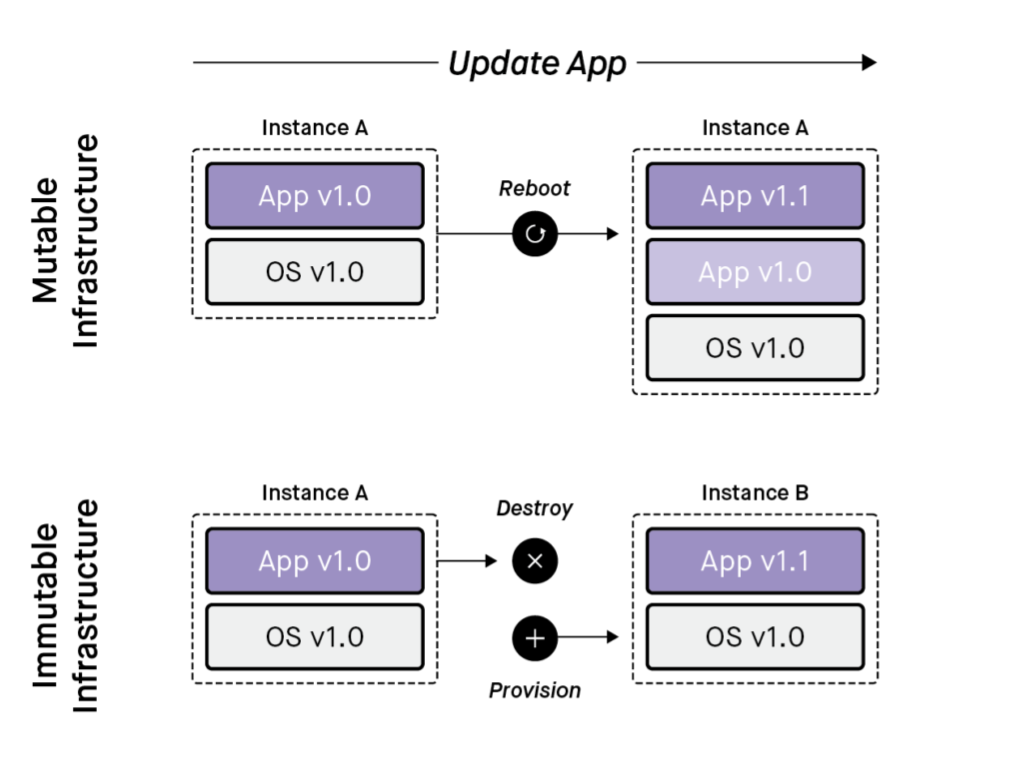

Immutability is the concept of once an application is running, it cannot be modified. When said application needs modifications or updates, rather than apply numerous changes and patches, the application is discarded, and the new version takes its place.

Employing a “destroy and provision” approach gives the major advantage of keeping the application lightweight rather than burdening it with patches over the years. A perfect example to this is the Windows operating system. While the first installation may not be too cumbersome, over the years, countless updates and patches will eventually increase its size, increase the code complexity and possibly introduce news bugs and vulnerabilities.

Figure 4 below illustrates the comparison between updating an application in a mutable infrastructure (Windows in our previous example) as opposed to an immutable infrastructure.

Figure 4 Updating an application in mutable and immutable infrastructures. Source: (Stella, 2016)

Immutable infrastructures come fully into effect in the case of unikernel applications. Since unikernels are designed to be developed and deployed, without the possibility to remotely connect to it, unikernels are immutable by design. Furthermore, their fast boot times allows for possibilities of seamless updates without interruption (e.g.: the IncludeOS Liveupdate functionality).

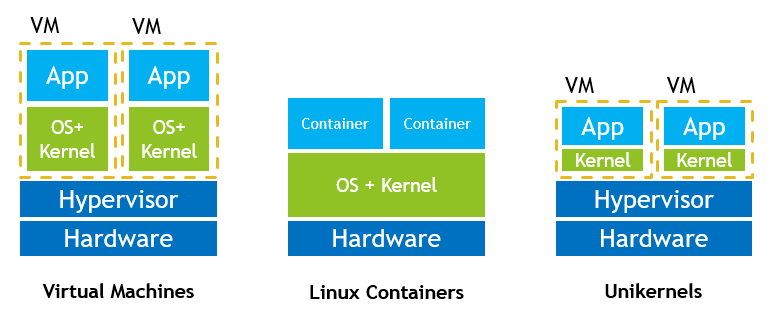

Virtualization of services can be implemented in various ways. One of the most widespread methods today is through virtual machine, hosted on hypervisors such as VMware’s ESXi or Linux Foundation’s Xen Project.

Hypervisors, amongst other things, allow hosting multiple guest operating systems on a single physical machine. These guest operating systems are executed in what is called virtual machines. The widespread use of hypervisors is due to their ability to better distribute and optimize the workload on the physical servers as opposed to legacy infrastructures of one operating system per physical server.

Containers are another method of virtualization, which differentiates from hypervisors by creating virtualized environments and sharing the host’s kernel. This provides a lighter approach to hypervisors which requires each guest to have their copy of the operating system kernel, making a hypervisor-virtualized environment resource heavy in contrast to containers which share parts of the existing operating system.

As aforementioned, unikernels leverage the abstraction of hypervisors in addition to using library operating systems to only include the required kernel routines alongside the application to present the lightest of all three solutions.

Figure 3 Comparison between virtual machines, Linux Containers (in this case Docker) and unikernels.

Figure 3 above shows the major difference between the three virtualization technologies. Here we can clearly see that virtual machines present a much larger load on the infrastructure as opposed to containers and unikernels.

Additionally, unikernels are in direct “competition” with containers. By providing services in the form of reduced virtual machines, unikernels improve on the container model by its increased security. By sharing the host kernel, containerized applications share the same vulnerabilities as the host operating system. Furthermore, containers do not possess the same level of host/guest isolation as hypervisors/virtual machines, potentially making container breaches more damaging than both virtual machines and unikernels.

| Technology | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual Machines | - Allows deploying different operating systems on a single host - Complete isolation from host - Orchestration solutions available |

- Requires compute power proportional to number of instances - Requires large infrastructures - Each instance loads an entire operating system |

| Linux Containers | - Lightweight virtualization - Fast boot times - Ochestration solutions - Dynamic resource allocation |

- Reduced isolation between host and guest due to shared kernel - Less flexible (i.e.: dependent on host kernel) - Network is less flexible |

| Unikernels | - Lightweight images - Specialized application - Complete isolation from host - Higher security against absent functionalities (e.g.: remote command execution) |

- Not mature enough yet for production - Requires developing applications from the grounds up - Limited deployment possibilities - Lack of complete IDE support - Static resource allocation - Lack of orchestration tools |

This section introduces the unikernel projects at the time of this writing (February 2018), newest unikernel solutions have also been added to the list. After explaining the various projects, a comparison is established to determine the best candidate for a proof-of-concept.

Feel free to submit a pull request to this repository to add a solution. See the contributions guidelines on how to do that

MiniOS is a small operating system kernel that is included with the Xen project hypervisor. Since 2015 it has its own GitHub and has been the root for many unikernel projects because of its included kernel drivers for the Xen hypervisor. Projects based on MiniOS include ClickOS and MirageOS.

As opposed to most “general pupose” projects, ClickOS is specialized in network devices using Network Function Virtualization (NFV). Presented in 2014 at the USENIX symposium, the project has been active on GitHub since the year 2000 and is still maintained but has seen very few activity over the last few years.

Maintained by NEC Laboratories Europe, the project offers network middlebox virtual machines with small footprint (5MB in size with 30ms boot time) and high network throughput on 10 Gigabits per second interfaces.

Written in C++, ClickOS virtual machines are constructed based on the Xen Project’s MiniOS and are designed to run on a Xen hypervisor.

Released by Galois Inc., HalVM is a port of the Glasgow Haskell Compiler that allows developers to write applications in Haskell and compile them to a unikernel appliance ready for deployment on Xen hypervisor.

Currently maintained on GitHub, the project is still active in version 2.0 and is in the process of updating to 2.5 with a refactor planned for 3.0 (although this refactor was planned for 2017 (Wick, HaLVM v3: The Vision, The Plan, 2016)).

Prototype currently under development (v0.11 as of February 2018) for writing unikernel applications in C++. Unlike most projects, Include OS is designed to run on KVM, VirtualBox and VMWare with additional support for cloud providers such as Google Compute Engine, OpenStack and VMWare vCloud.

While IncludeOS is still in prototype and maintained on GitHub, the project already proposes an orchestration tool called Mothership for configuring, deploying and managing IncludeOS applications.

One of the first projects on unikernels, MirageOS is a library operating system containing various libraries used to build unikernel applications. Applications are written in OCaml, development is done using libraries that are transformed to kernel routines when compiled to a unikernel image. Images generated with MirageOS are deployable to Xen, KVM/QEMU hypervisors and RTOS/MCU. The project is still maintained on GitHub, with version 3.0 released in February 2017.

Made by NanoVMs, industry-ready unikernel provider. Unlike others that require porting, this runs any valid ELF binary. And can also run other JIT compiled languages like Python, Node, PHP etc. For now, it runs on the KVM/QEMU hypervisor, Xen, ESX, and Hyper-V so supports both AWS && Google Cloud as well, but they say that they do have plans on adding more.

The kernel is open source and found at Github and it provides a compilation and orchestration tool called Ops which is open source and maintained on GitHub

OSv is particular; it allows porting various applications written in various languages to a unikernel by integrating some kernel functions built-in. Therefore, it is not as light as a fully compiled unikernel, however it provides support for many languages including Java, C, C++, Node and Ruby. It can also be run on a variety of platforms such as VirtualBox, VMWare ESXi, KVM, Amazon EC2 and Google Compute Engine. Virtual appliances with widely used applications are also directly available (Memcached, redis and Apache Cassandra).

Originally developed by a Cloudius Systems, the company changed to ScyllaDB and has shifted focus away from OSv. The project is still active but mainly supported by the community on GitHub.

Rumprun is an implementation of the Rump kernel2 that allows to transform most of POSIX-compatible applications into unikernel variants. The NetBSD inspiration of the Rump kernel makes it possible to port many applications to unikernel without requiring large amounts of modifications to the application code itself.

Rumprun also supports applications written in other languages such as C, C++, Erlang, Go, Java, Javascript (node.js), Python, Ruby and Rust and can run on both Xen and KVM. The project is still maintained on GitHub.

2 Note: Rump kernels are composed of drivers designed to match closely the originals without requiring rewriting to accommodate heterogeneous operating systems. The rump kernel was designed to be minimal but highly portable.

Unik is not a unikernel nor a library operating system per se, but rather a partial orchestration tool. Written in the Go language, it is a toolbox that allows compilation of application code as well as running and managing unikernels across various cloud providers.

Unik makes use of unikernels and can compile applications into unikernel images using rumprun, OSv, IncludeOS and MirageOS. Additionally, Unik can run and manage these unikernels locally on VirtualBox or full-fledged hypervisors such as Xen, KVM or vSphere, as well as on the cloud on Amazon AWS, Google Cloud and OpenStack.

Unik also exposes a REST API in order to allow integration with orchestration tools such as Kubernetes or Cloud Foundry.

Developed by the LSUB research team at Universidad Rey Juan Carlos of Madrid, Clive is announced as “an operating system designed to work in distributed and cloud computing environments” (Unikernels - Rethinking Cloud Infrastructure, n.d.). Written in Go and compiled with a custom compiler, there are few examples of use cases of implementation and the GitHub has been inactive for close to two years. No official statement has been given regarding the maintaining of the project.

Drawbridge was a Microsoft Research project that aimed to modify the Windows 7 kernel structure in order to reduce the number of system calls to the kernel. This was done by “refactoring” and moving routines typically present in the kernel space to the user space. This was combined with process isolation called “picoprocess”.

However, while this approach allows lighter application processes, it still heavily relies on the presence of a kernel in a “hypervisor-like” structure. Furthermore, the kernel functions moved to user space remain intact and include routines that may not be used by the application. As a result, while drawbridge is a loose implementation of library operating systems, they greatly differ from unikernels in effect.

Very little to no information is available concerning how to implement it into a Windows operating system.

GUK (Project Guest VM Microkernel) was an enhanced version of the minimalistic MiniOS operating system which allows to construct unikernel like systems by loading the required modules onto the microkernel. The project has been inactive since its fork in 2011.

The product of the Erlang-on-Xen project which aimed at creating applications written in Erlang on the Xen hypervisor. The project site has several use cases where unikernel projects could be implemented as well as demos and stats of LING’s website running on a unikernel.

Unfortunately, the LING repository on GitHub has not been updated since 2015 (as of February 2018).

Runtime.js is a library operating system designed to run JavaScript applications with compatibility with the Node.js API. The only hypervisor supported is KVM.

As of October 2017, the project is no longer maintained and is not ready for production in its current state (GitHub).

Toro is an unikernel that proposes a dedicated API to develop microservices. The main difference with other unikernels is that Toro proposes the programmer to develop the application by relying on Toro's API. Toro is made of five FreePascal units: Processes, Memory, Filesystem, Networking, and Devices. These units provide a simple interface to the user's application. For example, Processes provides the API to handle threads whereas Filesystem provides the API to allow the accessing to files. In the case of Networking, Toro proposes two models to develop microservices: blocking and non-blocking sockets. The former is for microservices that do IO and the latter for those that they can answer requests without the need of any blocking call. Non-blocking sockets are handled by relying on the single thread event loop model in which one thread is used for each microservice. This implementation allows Toro to support many concurrent connections by reducing the number of context switches. In Toro, the kernel and the microservices are compiled together which results in an image that can be deployed in a cloud provider. For more information about the project, please see at GitHub.

Unikraft is an automated system for building specialized POSIX-compliant OSes known as unikernels; these images are tailored to the needs of specific applications. Unikraft is based around the concept of small, modular libraries, each providing a part of the functionality commonly found in an operating system (e.g., memory allocation, scheduling, filesystem support, network stack, etc.). Unikraft is an open source project and may be found at Github.

Out of the various existing projects, some standout due to their wide range of supported languages. Out of the active projects, the following table resumes the language they support, the hypervisors they can run on and remarks concerning their functionality.

| Unikernel | Language | Targets | Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| ClickOS | C++ | Xen | Network Function Virtualization |

| HalVM | Haskell | Xen | |

| IncludeOS | C++ | KVM, VirtualBox, ESXi, Google Cloud, OpenStack | Orchestration tool available |

| MirageOS | OCaml | KVM, Xen, RTOS/MCU | |

| Nanos Unikernel | C, C++, Go, Java, Node.js, Python, Rust, Ruby, PHP, etc | QEMU/KVM, XEN, ESXi, Amazon EC2, Google Cloud, HyperV | Orchestration tool available |

| OSv | Java, C, C++, Node, Ruby | VirtualBox, ESXi, KVM, Amazon EC2, Google Cloud | Cloud and IoT (ARM) |

| Rumprun | C, C++, Erlang, Go, Java, JavaScript, Node.js, Python, Ruby, Rust | Xen, KVM | |

| Unik | Go, Node.js, Java, C, C++, Python, OCaml | VirtualBox, ESXi, KVM, XEN, Amazon EC2, Google Cloud, OpenStack, PhotonController | Unikernel compiler toolbox with orchestration possible through Kubernetes and Cloud Foundry |

| ToroKernel | FreePascal | VirtualBox, KVM, XEN, HyperV | Unikernel dedicated to run microservices |

| Unikraft | C, C++, Rust, GO, Python etc. | KVM, XEN, Linux | Orchestration tool available |

After researching the existing solutions from which to create unikernel, the next step of the project was to evaluate its capacities in a production environment. This would allow gaining more insight into the life cycle of developing a unikernel for specific applications.

The unikernel environment will be created through a proof of concept. As will be defined later, the proof of concept environment will be virtualized on a Linux operating system with the QEMU hypervisor.

The evaluation of the unikernels shall be done against their closest homologues in terms of service minimization, by deploying the same architecture as the unikernels’ proof of concept using container technologies.

Once both infrastructures have been developed and are stable, a benchmark will be executed on both the unikernel and the container environment. Through this benchmark we shall evaluate elements such as boot times, processor and memory usage, local storage access and potentially load stress testing. Unfortunately, penetration testing will not be covered in this benchmark due to the complexities of evaluation and the time constraints of the project.

As highlighted by the table in Comparing Solutions, numerous options are available depending on the programming language used for an application as well as the desired supporting platforms. Unfortunately, not all platforms are supported for all languages.

Our initial choice for deploying a proof of concept was to use Unik for its wide range of supported platform, including OpenStack. Additionally, its ability to directly integrate with the Kubernetes orchestration tool made it an ideal candidate. However early testing of the solution proved it to be non-functional when attempting to compile and execute example unikernel applications provided by the repository. Due to the lack of reactivity from the maintainers of the project regarding recent issues, including issues encountered during our initial test, we had to discard Unik as a potential candidate (see issue #2 on this repository as well as issue # 152 on the Unik repository).

Our second choice shifted to IncludeOS for similar reasons: supported platforms including OpenStack, and its orchestration tool possibilities. One of the main drawback is that it only supports the C++ language (as opposed to Unik’s broader list of languages). While this should not prove to be an issue for our proof of concept, however it does reduce its scope of potential interested parties willing to create unikernel applications to developers proficient in C++.

Another potential candidate we envisioned for this proof of concepts was MirageOS. This was mainly due to its amount of documentation and the activity present on the project’s Git repository. Unfortunately, while the OCaml language was one of its drawback, the most prominent disadvantage was the supported platform being limited to Xen hypervisors.

Lastly, the remaining potential candidates were OSv and Rumprun for their large selections of supported languages and, in the case of OSv, the supported platforms. However, both options were kept as last resort solutions mainly due to their technology, as they do not entirely behave as unikernels. Both employ kernels larger than needed by including functions unused by the compiled application code.

To best compare the advantages of unikernels to alternatives like Linux Containers, we opted to implement a selection of services to be able to evaluate them in different areas of effect.

As such, we will create multiple unikernel in a topology as follows:

- A REST Web Server offering a simple web page;

- A DNS server, resolving the address of the web server;

- A router connecting the external network to the Web and DNS servers;

- A firewall filtering the incoming packets to the router, blocking any ICMP Echo request/reply messages.

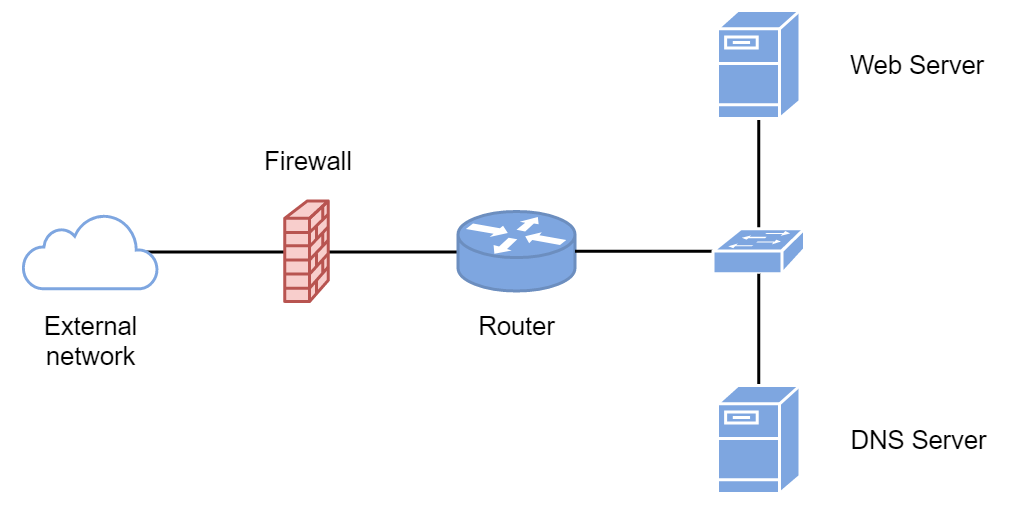

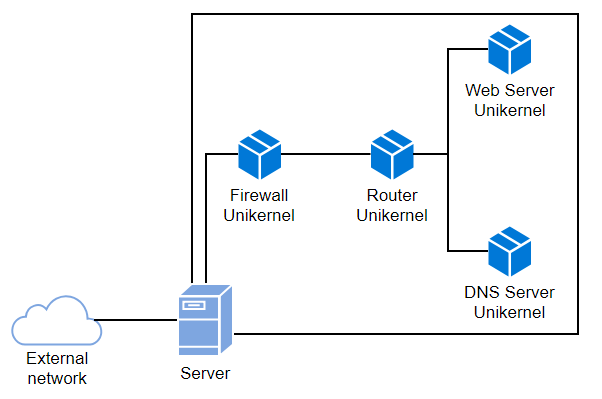

Both the web server and the DNS will be in a DMZ like network, with a router connecting it to the external network and the firewall filtering incoming connections to the router. Figure 5 and figure 6 below represent the topology that will be deployed in a hypervisor environment.

Figure 5 Logical representation of the Proof of Concept topology.

Figure 6 Physical representation of the Proof of Concept topology.

All unikernels will be executed on a Linux based machine in a QEMU/KVM hypervisor. QEMU is chosen as the hypervisor because it is the default hypervisor used by IncludeOS, but also because of the current limitations in the IncludeOS network stack drivers which causes issues when trying to execute unikernels in hypervisors like VMware Workstation or VirtualBox.

To create unikernels using IncludeOS, the first step is to install the IncludeOS binaries. This is straightforward, following the instructions from the Github project page, clone the repository onto a local Linux machine and install using the provided script. Some variables can be exported globally to manipulate where the binaries should install.

With IncludeOS installed, a hypervisor environment is required to run the unikernel containers. It is important to note that IncludeOS installs QEMU during its own installation because it is the default hypervisor.

In the case of our current proof of concept, our main task to prepare the hypervisor environment is to setup the various virtual networks that will be used by the unikernel virtual machines. Once the virtualized environment is prepared, the unikernels can be developed. IncludeOS provides a sample skeleton directory structure containing the base required files for compiling a unikernel.

To build a unikernel, IncludeOS makes use of the cmake command to create build files from the configurations files in the skeleton directory. These files specify various project properties, but most importantly link the project to the specified libraries for the C++ code as well as specify the desired drivers to integrate into the unikernel image. Once the build files have been created, the make command is used to compile the unikernel into an image file, which can then be booted on using the QEMU hypervisor.

The files used by the cmake command are very important in the construction of the IncludeOS unikernel. Following is a list of files that need to be configured accordingly in our proof of concept depending on the unikernel image to build.

CMakeLists.txt indicates to cmake some project variables such as the project name, the files containing the C++ code to be linked with which OS libraries to form a bootable image as well as the drivers to be included in the OS. Additionally, it also imports IncludeOS routines for building the unikernel image. This file must be carefully reviewed depending on what OS devices the application needs to access and the destination hypervisor. For example, in the case of the web server, we need to access the network device, thus we need to specify the network driver, which can be “virtionet” if we use QEMU/KVM/VirtualBox or “vmxnet3” for VMware.

Config.json holds the configuration for the operating system such as the network device configuration, vlans, routes to implement in case of a router, terminal interfaces to include and so on. While little documentation exists on what those files can contain, IncludeOS also includes another possibility of configuring the operating system through a custom script written in what they call NaCl. These custom scripts can be used instead of the config.json file with the same syntax (see the firewall unikernel source code).

The dependencies.cmake is not a required file, but it can be used to gather external dependencies such as external git repositories to clone when compiling. In one of the examples present in the IncludeOS repository, this file clones an external C++ library (developed by the same people at IncludeOS).

The vm.json is not required either and is used mainly for QEMU parameters when using the IncludeOS boot command which executes QEMU in the background to boot on a unikernel image.

Service.cpp contains the entry point to the unikernel application. This file must contain a void Service::start() {} method as the starting point of the application. The libraries to use in the C++ code destined for an IncludeOS unikernel should be those provided by the project. While all the code can be contained in a single file, it can be split into different files as well, however it is important to notify cmake which files to include in the CMakeLists.txt file.

In order the compare unikernels to an established technology with similar scope (i.e.: minimal footprint), containers were retained as the best solution for comparison. The specific technology chosen was Docker containers due to their presence in industrial deployments and the existence of orchestration tools.

Building the container images required two major steps:

- Porting the C++ code from the unikernels to the containers;

- Creating the Dockerfiles to create the containers with the ported code.

The possibilities for porting the code differed with varying degrees of complexity:

- Compiling the IncludeOS C++ code using the IncludeOS libraries in a container for execution.

- This approach would allow keeping the code identical to the original, however most libraries are written for a different kernel and could potentially not function on execution.

- Rewriting the code in C++ using standard libraries.

- This method allows to ensure compatibility with the containers, however creates complexity in the need to adapt the code to be as identical as possible to the IncludeOS code.

- On the other hand, this method more closely resembles a real-life scenario, where a developer would code differently based on the target platform.

- Using the IncludeOS Docker image to run the IncludeOS code in container.

- This is the least interesting method of porting because the IncludeOS container executes QEMU inside a container, effectively making it a nested virtualization, which is outside the scope of the benchmark (i.e.: using a comparable baseline).

The porting option selected was to rewrite the code in C++ using standard libraries, which proved challenging. To maintain the comparison as close as possible, the objective was to maintain the container C++ code as identical as possible to the unikernel code. This was hindered by the discrepancies present between the IncludeOS library implementations and the existing C++ libraries. This required exploring the IncludeOS libraries and code examples to find the required methods and their implementation.

As a result, some portions of the code are remained as identical as possible, while others are adapted as closely as possible to resemble the same processing steps as to not bias any benchmark.

Due to these discrepancies and lack of documentation of the APIs developed by IncludeOS, the time frame allocated for this project did not permit porting the entirety of the infrastructure from unikernels to containers.

Having successfully ported two applications from unikernels to containers, however, the next step was to create the containers to execute the C++ applications. To maintain the same scope as unikernels, which is to make the application as lightweight as possible, the base image for the containers was a crucial decision.

This minimal approach constraint required for the compilation to be performed on a different container than the destination container. This would allow the destination image to remain small without including all the compilation tools and unnecessary libraries.

The smallest Docker base image containers found were Busybox, at 1.15MB, and Alpine, at 4.15MB. Due to compilation requiring installing utilities like g++ and the C++ libraries, and Busybox not providing any package managers by default, Alpine was used for both compilation and execution.

Based on these findings, two containers were created:

- A container for compiling the C++ code on the same base image as the destination (Alpine in this case)

- This container was created with the gcc and g++ compilers pre-installed

- A container for each service with the binary executable compiled by the compiler container

The compilation process is plainly executed in command line, where the compiler container is run for the compilation process, stopped once finished and then removed. The compilation command is passed directly inline with the Docker command.

Due to portability issues, and the desire to not download the entirety of the C++ libraries, the C++ code was compiled by statically linking the libraries. The application container is then created by copying to binary to the container image. Executing the containers will start the service which will listen for requests on its first active interface.

After deploying unikernels in the proof of concept topology and porting some of the unikernel applications to containers, it was possible to examine a few metrics regarding unikernels and how they compare to containers.

The first data available after compiling the unikernels is the image size. As summarized by the table below, unikernel images are very lightweight considering the fact that they contain a small kernel in addition to the application code.

| Unikernel | Image Size |

|---|---|

| DNS Server | 3,3 MB |

| Web Server | 3,5 MB |

| Router | 3,4 MB |

| Firewall | 3,2 MB |

In contrast, the container table below presents the image size for the Web and DNS servers as they were built using the ported code from unikernels. The Alpine base image size is also included for reference.

| Container | Image Size |

|---|---|

| Alpine Docker base image | 4,15 MB |

| DNS Server | 9,82 MB |

| Web Server | 10,1 MB |

As can be seen by the tables above, even though unikernels include a partial kernel, the container images are almost three times larger than unikernels.

An additional attempt at determining early metrics was to determine the minimum amount of resources that could be attributed to a unikernel while remaining functional.

In the proof of concept deployment, analysis of the unikernel applications showed that at idle, memory consumption varied between 85 and 90 megabytes of memory. Memory allocation by the hypervisor was reduced to 128MB for each unikernel which implied approximately 66 to 70 percent of RAM utilization at idle.

In contrast, the DNS and Web server containers used only around 680 kilobytes of memory, representing only 0.53 percent of the 128MB allocated to unikernels.

Processor utilization cannot be used for comparison due to limitations of unikernels to a single core. This limitation is mainly imposed by the lack of process management functions in the unikernels limiting the use of multiprocessing. This limitation is voluntary in order to reduce the kernel size. Unikernels are, however, capable of multi-threading applications.

Containers on the other hand do not suffer this limitation and are able to be fully multi-processor capable by default (unless explicitly specified at creation time).

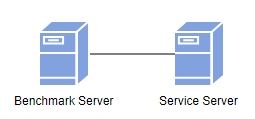

The benchmark environment was composed of two Dell servers with Intel Xeon CPU E31220L @ 2.20GHz (1 socket per server) and 32GB of RAM.

The servers were setup as one server acting as the benchmark client, while the other hosted the services (either the unikernels or the containers depending on the benchmark being executed) as indicated by Figure 6 below.

Figure 6 Benchmarking environment

The hypervisors deployed on the server hosting the service applications were:

- QEMU with KVM as management layer for the unikernels

- Docker CE for the containers

As for the benchmarking use cases, three were established:

- Benchmarking the DNS server as a standalone service (i.e.: it is the only service running on the server)

- Benchmarking the web server as a standalone service

- Benchmarking the boot times of services in a simulated orchestration environment

Note: due to time constraints during the project, only a limited number of the unikernel applications were ported to containers, thus only the DNS and Web services are presented in the following benchmarks.

To compare the unikernels and container solutions, a series of benchmarks have been established to evaluate both solutions. The areas that will be evaluated are performance, resilience and boot time. Due to complexity of benchmarking procedures, the security aspect of the unikernel will not be tested. The following paragraphs will more clearly outline the goal of each test.

In the performance aspect the objective is to measure the response time of the DNS and web services under normal loads. In the resilience test the objective is to measure the response time under conditions of heavy loads, such as simulated denial of service attacks, and see how long the services last until a noticeable degradation in service is present.

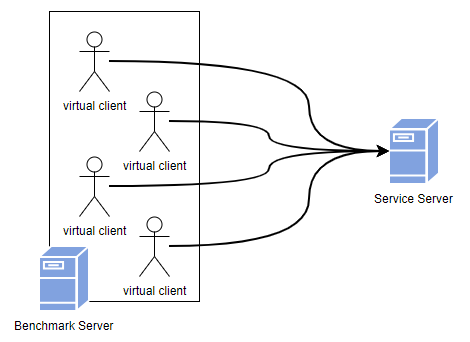

The performance and resilience benchmarks are combined into a single test where the benchmark server simulates 100 connections, which will perform requests to the service at an increasing frequency. Thus, as the frequency of the requests increase, the benchmark will progressively transition from a performance benchmark to a resilience benchmark.

Figure 7 Performance and resilience benchmark

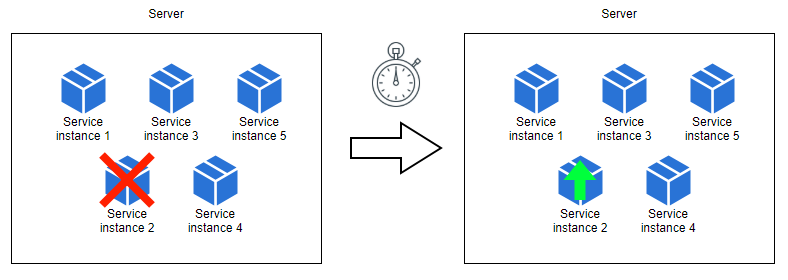

The boot time aspect is measured for potential orchestration evaluations: in the case of a unikernel or container going offline, how long will it take for the application to get back up and running.

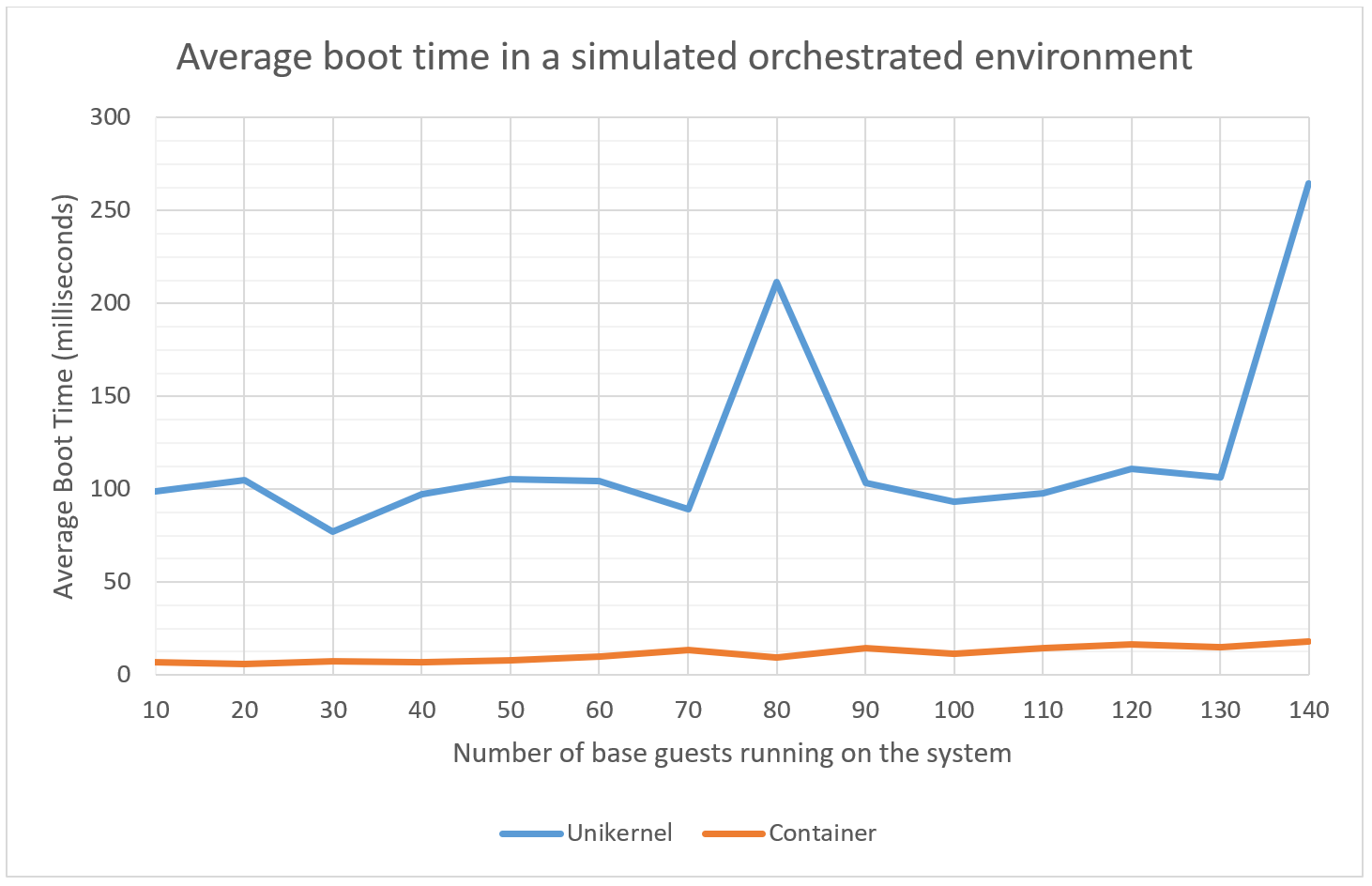

The boot time benchmark is performed by launching a defined number of service instances, either unikernels or containers, and shutting down a random instance; simulating either a failure, an attack or an update (due to immutability or unikernels). The time between the startup command and when the service is available is then recorded. The number of instances is increased over time to determine whether the number of instances has an impact on orchestration performances.

Figure 8 Boot time benchmark in a simulated orchestration environment

The chosen utility to benchmark the DNS server is Nominum’s DNSPerf tool. This command-line utility is multi-threaded and can be configured to emulate multiple clients and specify the number of queries per second. The test results are presented as a summary of queries sent, completed and lost. Being a command line tool, it can be easily integrated into scripts for automated benchmarking test cases.

For the web server, Gil Tene’s wrk2 is the retained solution for its configurable parameters similar to DNSPerf: specify the number of requests, the number of clients and the duration of the test. Wrk2 is also multi-threaded and presents results with metrics such as response time, transaction rate and throughput.

To measure the boot times of unikernels and container, a python script will be used to launch and power down unikernel/container instances and measure the time between executing the command and when the service is operational.

In the benchmarks performed, the Unikernel applications are considered as the subject of the benchmark, while the comparator is the Docker applications deployed using the same code used for unikernels but adapted based on API differences in the C++ libraries.

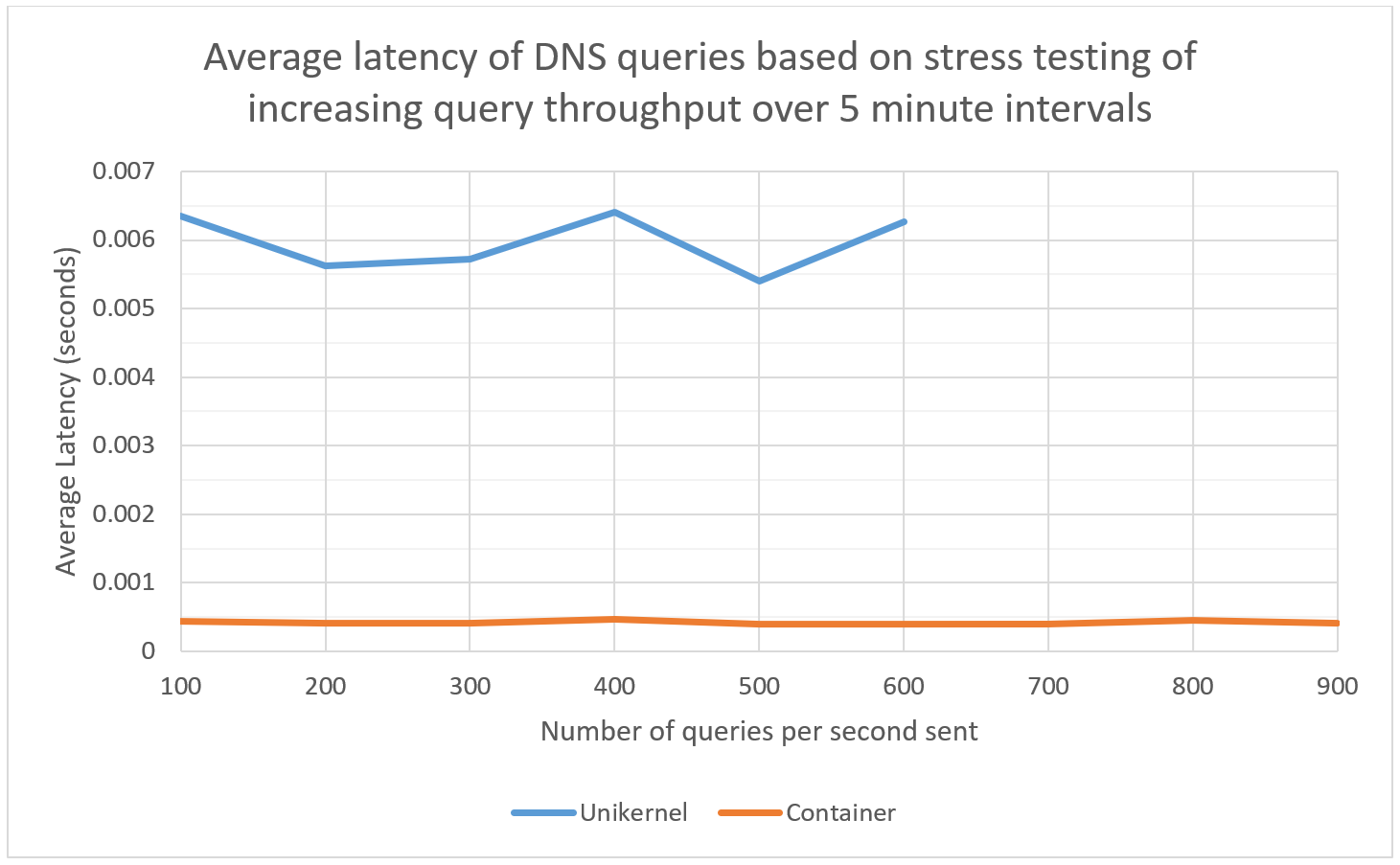

To stress the server, an increasing number of requests per seconds are generated and incremented at 5-minute intervals. Starting at 100 queries per seconds, every 5 minutes the frequency is incremented by 100 until the server crashes.

As indicated by the graph, despite being announced as highly performant cloud ready application solutions, the stateless unikernel DNS implementation seems to have difficulties coping with a growing throughput of queries. As for the container, the average latency seems to remain consistent throughout the test.

Note that at the 600 queries per second mark, the latency became too important and was pulled from the graph for readability reasons.

Over the 900 queries per second mark, the data retrieved showed that the unikernel application refused to process requests beyond this throughput. Thus, the remainder of the container statistics have been excluded. As explained later in the analysis, this could be due to a bug in the UDP library implementation of the IncludeOS project (reported to developers, see issue #1772 & issue #3).

NOTE: The performance issues encountered were caused by serial output being performed during execution. Supressing the output allowed higher throughput from the server as was evidenced here.

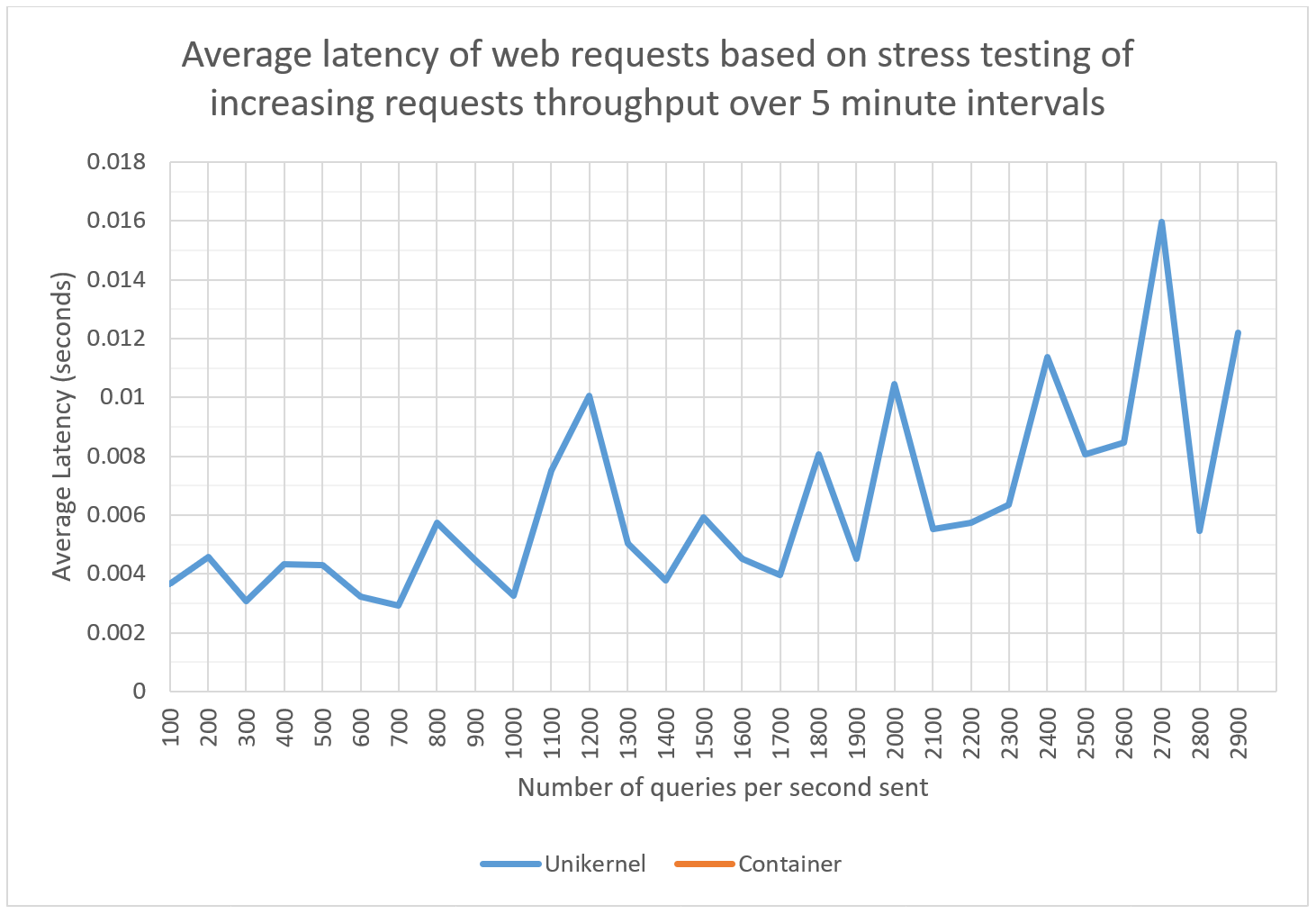

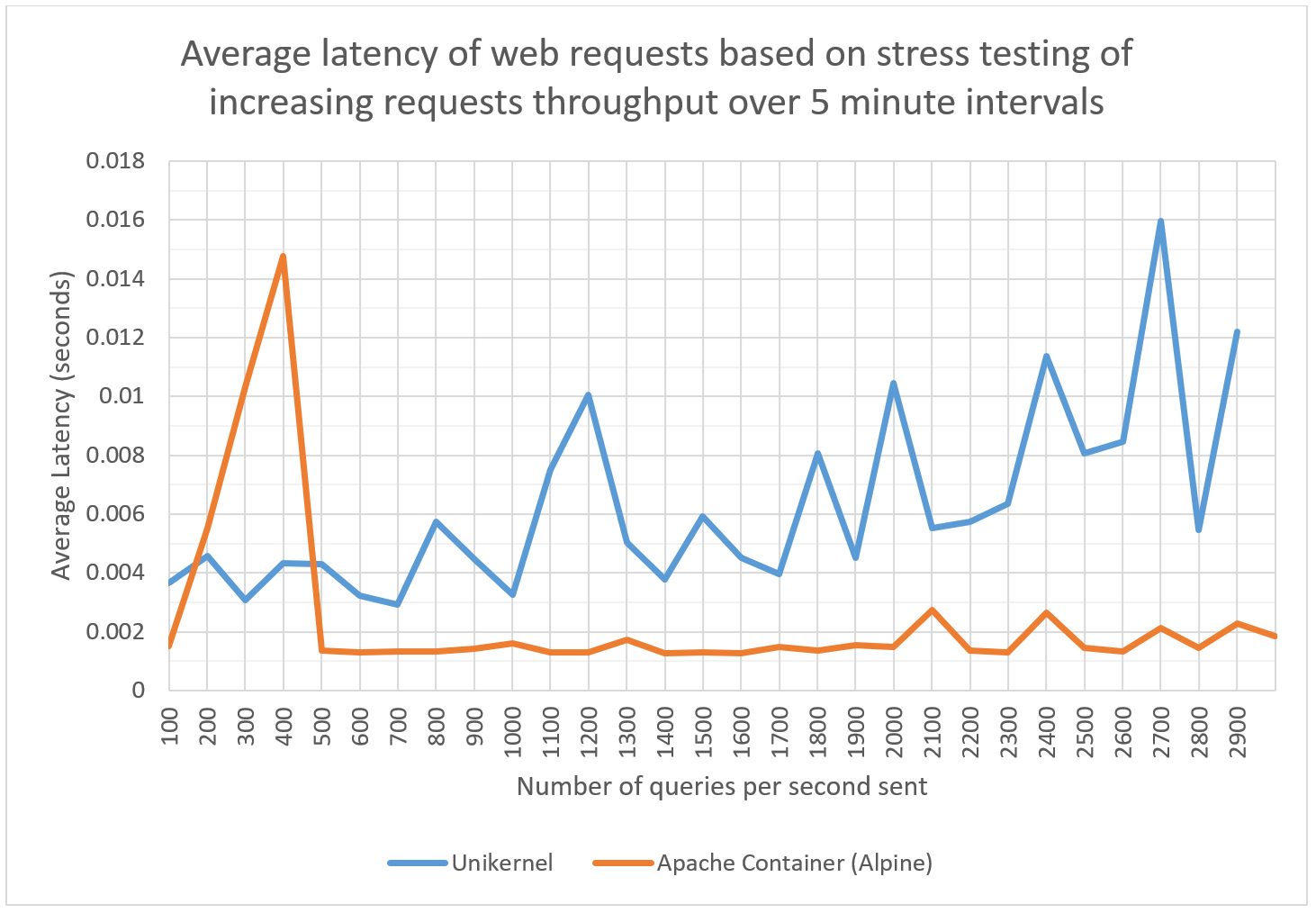

For the web server test, a similar stress testing was conducted. The methodology is once again to increase the number of requests per second. Starting at 100 requests per second over a 5-minute period, the number of requests is incremented by steps of 100 until the web service stops responding.

As presented above, the average response time does not appear consistent across the different number of query throughputs. Furthermore, around the 2900 queries per second mark, a similar issue to the DNS server was noted, where the web server refused to process requests at a higher throughput.

Concerning the container, unfortunately no data was retrieved due to the service refusing to respond to the benchmarking tool’s requests. This could be explained by a difference in code: the IncludeOS implementation is much more complex than the container counterpart, due to the vast number of custom libraries aimed at web server management. In contrast, the container required a much more simplistic approach using standard TCP sockets. This same simplistic code could not be ported to IncludeOS because of the lack of simple TCP socket implementation in the IncludeOS libraries.

To counter this issue, and to obtain some data to compare the unikernels to, an Apache container was used. Still based around a lightweight Alpine base, this image is out of the benchmark scope and somewhat biases the benchmark.

Despite the larger image size and the more complex code, the unikernel present a higher and less stable response time as opposed to the container. One exception remains from the 100 to 400 queries per second, where the response time from the Apache server increases linearly. Speculation for this behavior points to caching mechanisms, however the matter was not investigated further.

For the boot time scenario, 10 unikernels/containers are launched as the initial run. Over a period of 20 minutes, random instances are shut down, then started up again. A timer records the time between when the startup command has been given and when the instance is reachable through its IP address. By the end of the 20-minute period, an additional 10 instances are launched, and the test is repeated. The incrementation takes place up to 140 instances running simultaneously.

The following graph represents the average boot time measured for unikernel virtual machines and containers.

As indicated by the figure above, containers present a much faster boot time as opposed to unikernels which take almost 10 times longer to boot on average.

Unfortunately, due to unforeseen challenges in the benchmarking process, the performance and resilience tests did not provide sufficient data to derive anything conclusive based on numbers.

However, based on a small data sample present in the DNS server application, within 600 DNS requests per second, the container does present a clear performance advantage over the unikernels. A potential explanation for these results, and the inability for the unikernel to go beyond 900 queries per second, could be an issue within the IncludeOS UDP implementation .

Regarding the web server performance, the unikernel presents a lack of consistency across the different request frequencies. Furthermore, despite being out of the benchmark scope, the Apache container still outperforms the more simplistic and lighter unikernel service.

The boot time benchmark however shows a clear indication that, unlike promoted, unikernels do not present a clear advantage in boot time over containers. A potential explanation is the lack of optimization for our hypervisor environment based on KVM/QEMU. However, this would be relatively inconsistent with IncludeOS’s choice of default hypervisor being QEMU and chosen for its performance potential.

To allow anyone who wishes to reproduce this project, a series of scripts have been written. Note that the scripts have been written and tested on an Ubuntu 16.04 system. Executing those scripts on another Linux based operating system may require some modifications.

While the initial desire of the project was to provide a Vagrant file for fully contained reproducibility, constraints within the project’s time frame have hindered their creation.

The scripts are divided into two main objectives:

- Deployment scripts: used for deploying the proof of concept environment as well as the container counterparts;

- Benchmarking scripts: used to reproduce the benchmarks executed for this project.

The deployment scripts are divided into three parts: a pre-deployment, a unikernel deployment and a container deployment script.

The pre-deployment script installs all the required packages to deploy either the unikernel or the container deployment. The script clones the IncludeOS repository and installs the project, as well as installing the KVM utilities (QEMU being installed as part of IncludeOS) and the Docker engine.

The unikernels deployment script deploys the unikernel proof of concept environment developed for this project. The script builds the unikernel images from the source code, prepares the virtual networks then launches the unikernel instances.

This script does not deploy a client to test the deployment, to do so, a client virtual machine must be started and connected to the external network. The client IP configuration must be the Firewall external IP address as client’s default gateway (192.168.100.254 by default), and the DNS server’s IP address must be set as the client’s name server (10.0.0.100 by default).

The containers deployment script does not deploy the same proof of concept environment due to the constraints mentioned previously. However, the script builds and deploys the container images for the web and DNS server, exposing the ports 80 and 53 on the interface with internet connectivity by default.

The benchmarking scripts are varied, as there are scripts to launch the services to benchmark and scripts to launch the benchmark proper in addition to other miscellaneous scripts.

Prior to using any of the benchmarking scripts, it is imperative to use the pre-deployment script in order to install the pre-requisites and packages required to build the services to benchmark.

The benchmark tools installation script installs the tools used to perform the benchmarks, namely the wrk2 and dnsperf tools.

The bench_unikernel and bench_container scripts are bash scripts that launch the indicated service for benchmarking. Depending on the technology, the script will build either the unikernel or the container and deploy it to QEMU or Docker respectively. Note that for Docker containers, the ports are exposed via the Docker API, for unikernels however, the ports are redirected to the internal network through iptables rules (not automatically removed after virtual machine shutdown or deletion).

The bench_unikernel_cleanup removes the iptables rules created when launching a unikernel service for benchmark.

The python scripts launch the indicated benchmarks and are written for Python version 3. The DNS and web benchmark scripts require the destination IP address to be passed as argument, while the startup benchmark script requires the initial number of instances to start with. The results of the benchmarks are inserted into CSV files in the same directory as the scripts.

The DNS and web scripts are not programmed to stop and require manual intervention. The startup script on the other hand will stop after having reached 140 simultaneous instances.

Note that as a precaution for the benchmark, the startup script will shut down all Docker containers and QEMU virtual machines (will have undesired effects on non-development environments).

Lastly, the cleanup_all script cleans all the benchmark environment by removing the manual iptables entries and stopping and deleting all Docker container instances and QEMU virtual machines. This script should be reserved for a dedicated testing environment, due to the risk of losing existing virtual machines or containers.

The scripts have been mostly written to serve their specific purpose in a specific environment and have not been written with heterogeneity in mind. As such, there is room for improvement.

The best improvement would be to move from a scripted solution to a series of Vagrant files that would deploy an environment with the required tools to reproduce the project.

Another improvement would be to render the script more generic as opposed to Ubuntu-centric, due to the presence of sudo commands. This would however require launching some of the scripts as root, which, aside from being dangerous, could cause unexpected behaviors.

The Python benchmarking scripts could also be improved by using a more complete set of arguments to define the benchmark parameters with more granularity, as well as to detect when the DNS and web server are no longer responsive.

Unikernels are a new technology, but the principles on which they are based date from the early days of the operating system era. Those same principles have been re-used and adapted to new technologies available today to enhance their possibilities. The objective of this project was to explore the technology of unikernels and their possibilities in real-world applications.

Through the implementation of unikernels in an industry-proven topology, this project demonstrated that unikernels have potential to surpass containers on their size-on-disk footprint. With images not larger than 4MB, and resource utilization reduced to a strict minimum of a single core with 128MB of memory, unikernels have proved to be extremely lightweight for hosting an application with its own minimalistic operating system, whether it be a web server, DNS server, a router or a firewall.

However, despite achieving such objectives, unikernels also have their fair share of shortcomings. Notwithstanding some difficulties in the benchmarking process, unikernels seem to present little advantage over containers in terms of performance. While this could be explained by the technology’s newness, which has yet to fully breakthrough, it does prove that the technology still requires some improvement before being industry ready.

Another explanation could be linked to the IncludeOS project itself. Developing applications for unikernels certainly requires a different approach and special considerations, as opposed to developing applications for monolithic operating systems. This is even more true when the framework uses custom libraries lacking in-depth documentation.

Therefore, the belief is that while unikernels are an important innovation in the field of micro-services, the technology has not yet matured enough, nor has it been explored far enough by some projects. This is particularly well represented in the DNS benchmark performed, where the unikernel UDP implementation presented an important anomaly.

While IncludeOS presents a promising future, the lack of in-depth documentation mixed with the discrepancies in their custom API libraries will delay a more widespread adoption by the community.

Other unikernel projects may see the light of day, perhaps with more promising features, such as orchestration tool, or integration with existing orchestration tools. Such an integration would help spreading unikernels in existing infrastructures. However, the number of unikernel projects that spawn but are no longer maintained by either the original developers or the community greatly hinders the ability for unikernels to further evolve.

- Annoucing Release of GUK (Project Guest VM Microkernel). (2009, June 2). Retrieved February 2018, from Xen Project Blog: https://blog.xenproject.org/2009/06/02/annoucing-release-of-guk-project-guest-vm-microkernel/

- Ballesteros, F. (2014). The Clive Operating System.

- Ballesteros, F. (n.d.). Clive. Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/fjballest/clive

- Bratterud, A., Happe, A., & Duncan, B. (2017). Enhancing Cloud Security and Privacy: The Unikernel Solution. Eighth International Conference on Cloud Computing, GRIDs, and Virtualization. Athens, Greece. Retrieved February 12, 2018

- Bratterud, A., Walla, A.-A., Haugerud, H., Engelstad, P., & Begnum, K. (2015). IncludeOS: A minimal, resource efficient unikernel for cloud services. Cloud Computing Technology and Science (CloudCom), 2015 IEEE 7th International Conference (pp. 250-257). IEEE. Retrieved February 12, 2018

- Clive. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from Laboratorio de Sistemas: http://lsub.org/ls/clive.html

- Deploy Network Function Virtualization with IncludeOS Mothership. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from IncludeOS: http://www.includeos.com/mothership/index.html

- Drawbridge. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from Microsoft Research: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/project/drawbridge/

- Erlang on Xen. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from Erlang on Xen: http://erlangonxen.org/

- Galois Inc. (2016, December 4). Home - GaloisInc/HaLVM Wiki. Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/GaloisInc/HaLVM/wiki

- Galois Inc. (n.d.). The Haskell Lightweight Virtual Machine (HaLVM). Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/GaloisInc/HaLVM

- HiOA Dept. of Computer Science. (n.d.). IncludeOS. Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/hioa-cs/IncludeOS

- Hunt, G., Olinsky, R., & Howell, J. (2011, October 17). Drawbridge: A new form of virtualization for application sandboxing. (C. Torre, Interviewer) Retrieved February 2018, from https://channel9.msdn.com//shows//going+Deep//drawbridge-An-Experimental-Library-Operating-System

- IncludeOS. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from IncludeOS: http://www.includeos.org/

- Jordan, M. (n.d.). GUK. Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/Leonidas-from-XIV/guestvm-guk

- Kantee, A. (2016). The Design and Implementation of the Anykernel and Rump Kernels. Retrieved February 2018, from http://www.fixup.fi/misc/rumpkernel-book/

- Kohler, E. (n.d.). The Click Modular Router. Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/kohler/click

- Levine, I. (2016, May 6). UniK: Build and Run Unikernels with Ease. Retrieved February 2018, from solo.io: https://www.solo.io/single-post/2017/05/14/UniK-Build-and-Run-Unikernels-with-Ease

- ling: Erlang on Xen. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/cloudozer/ling

- Madhavapeddy, A., & Scott, D. (2013). Unikernels: Rise of the virtual library operating system. ACM Queue, 11(11), 30. Retrieved February 12, 2018

- Madhavapeddy, A., Mortier, R., Rotsos, C., Scott, D., Singh, B., Gazagnaire, T., . . . Crowcroft, J. (2013). Unikernels: Library Operating Systems for the Cloud. Retrieved February 6, 2018

- Martins, J., Ahmed, M., Raiciu, C., Olteanu, V., Honda, M., Bifulco, R., & Huici, F. (2014). ClickOS and the Art of Network Function Virtualization. Proceedings of the 11th USENIX Conference on Networked Systems Design and Implementation, (pp. 459-473). Retrieved February 2018

- Microkernels. (2015). In A. Tanenbaum, & H. Bos, Modern Operating Systems Fourth Edition (4th ed., pp. 65-68). Pearson Education, Inc.

- Mini-OS. (2018, February 7). Retrieved February 19, 2018, from Xen Project Wiki: https://wiki.xenproject.org/wiki/Mini-OS

- mirage. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/mirage/mirage

- MirageOS. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from MirageOS: https://mirage.io/

- MirageOS on RTOS/MCU, from MirageOS: https://mirage.io/blog/2018-esp32-booting

- MirageOS on KVM/QEMU, from MirageOS: https://mirage.io/blog/introducing-solo5

- osv. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/cloudius-systems/osv

- OSv - the operating system designed for the cloud. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from OSv: http://osv.io/

- Overview. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from ClickOS - Systems and Machine Learning: http://cnp.neclab.eu/projects/clickos/

- Pavlicek, R. (2017). Unikernels: Beyond Containers to the Next Generation of Cloud. O’Reilly Media.

- perbu. (2017, October 15). Introducing Liveupdate. Retrieved February 2018, from includeOS: http://www.includeos.org/blog/2017/liveupdate.html

- Popuri, S. (2018, February 7). Mini-OS-DevNotes. Retrieved February 19, 2018, from Xen Project Wiki: https://wiki.xenproject.org/wiki/Mini-OS-DevNotes

- Porter, D., Boyd-Wickizer, S., Howell, J., Olinsky, R., & Hunt, G. (2011, March). Rethinking the Library OS from the Top Down. ACM SIGPLAN Notices, 46(3), pp. 291-304. Retrieved February 2018

- Rump Kernels. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from Rump Kernels: http://rumpkernel.org/

- runtime.js - JavaScript Library Operating System for the Cloud. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from runtime.js: http://runtimejs.org/

- runtimejs/runtime. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/runtimejs/runtime

- solo-io/unik: The Unikernel Compilation and Deployment Platform. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/solo-io/unik

- Stella, J. (2016). Immutable Infrastructures. O,Reilly Media, Inc. Retrieved February 2018

- The Rumprun unikernel and toolchain for various platforms. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/rumpkernel/rumprun

- Unikernels - Rethinking Cloud Infrastructure. (n.d.). Retrieved February 6, 2018, from Unikernel: http://unikernel.org/

- Unikernels. (2016, October 15). Retrieved February 12, 2018, from Xen Project: https://wiki.xenproject.org/wiki/Unikernels

- Wick, A. (2016, April 29). HaLVM v3: The Vision, The Plan. Retrieved February 2018, from http://uhsure.com/halvm3.html

- Wick, A. (n.d.). HaLVM. Retrieved February 2018, from galois: https://galois.com/project/halvm/

- Wiki for rump kernels. (n.d.). Retrieved February 2018, from GitHub: https://github.com/rumpkernel/wiki

- Ali Raza, Parul Sohal, James Cadden, Jonathan Appavoo, Ulrich Drepper, Richard Jones, Orran Krieger, Renato Mancuso, and Larry Woodman. 2019. Unikernels: The Next Stage of Linux’s Dominance. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems (HotOS ’19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 7–13. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3317550.3321445

- https://github.com/seeker89/unikernels