A popular example of JavaScript engine is Chrome's V8 engine.

However, there are others such as Rhino for Mozilla, JavaScriptCore for Safari, Chakra for IE and even JerryScript for the Internet of Things.

The V8 engine translates JS code into more efficient machine code at execution time implementing a JIT (just-in-time) compiler.

It has several threads internally:

- The main thread fetches the code, compiles it and executes it.

- There is also a separate thread for compiling so that the main thread can keep executing with this one is optimizing code.

- A Profiler thread that will tell the runtime on which methods we spend a lot of time so they can be optimized.

- A few threads to handle Garbage Collector sweeps.

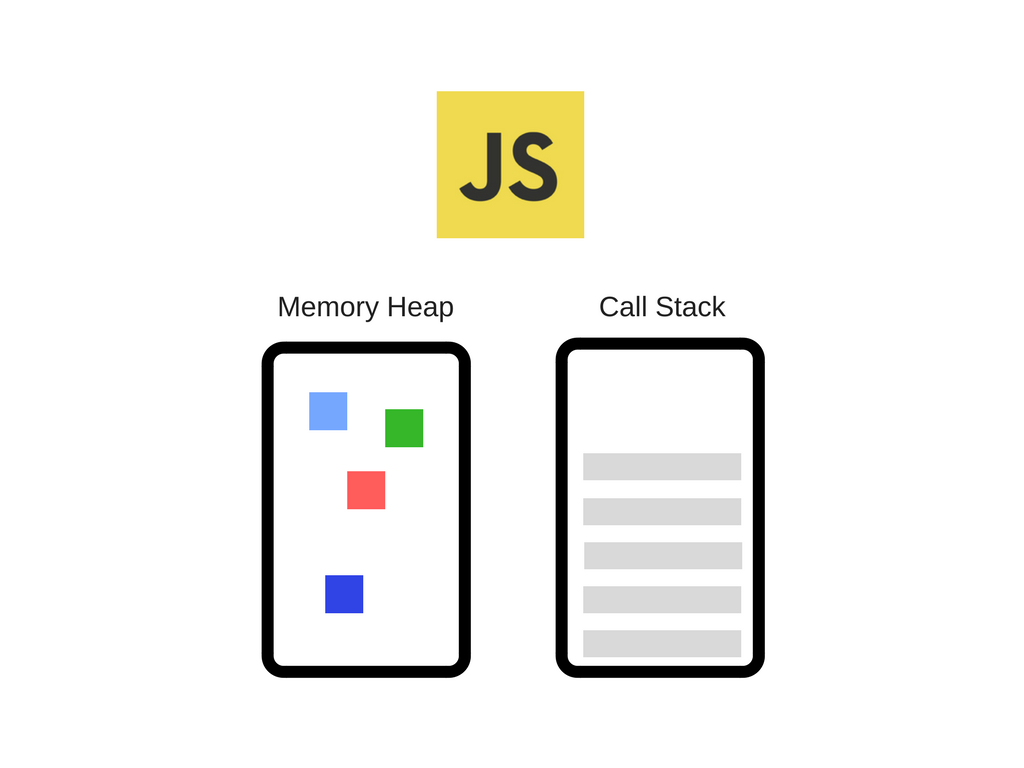

This engine is made of 2 main components:

- Memory Heap - where memory allocation happens

- Call stack - where stack frames are as the code executes

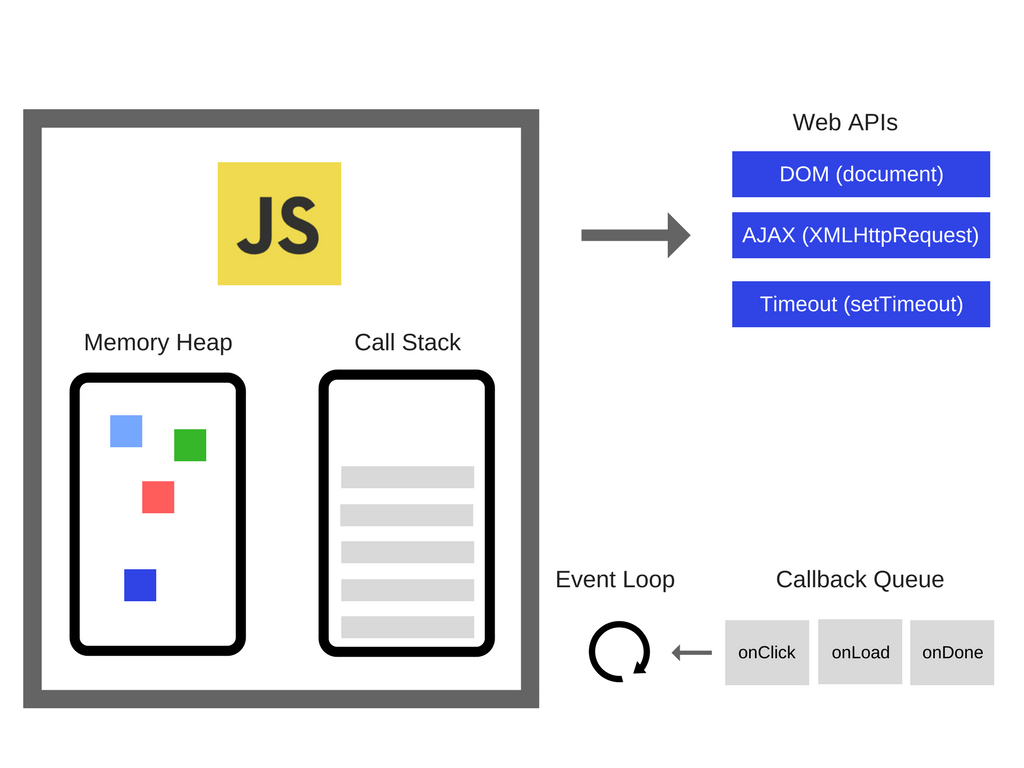

There are also very popular APIs that we use on a day-to-day basis in the browser that are not provided by the engine.

So, we have the engine, the web APIS, the event loop and the callback queue.

JavaScript has a single call stack as it is a single-threaded programming language, meaning, it can only do one thing at a time.

The call stack is a data structure that records where we are in the program. If we step into a function, we put it on top of the stack, if we return from a function, we pop off the top of the stack.

function multiply(x,y){

return x * y;

}

function printSquare(x){

var a = multiply(x,x);

console.log(a);

}

printSquare(4);So the steps in the engine will be the following:

Each entry in the call stack is called a stack frame.

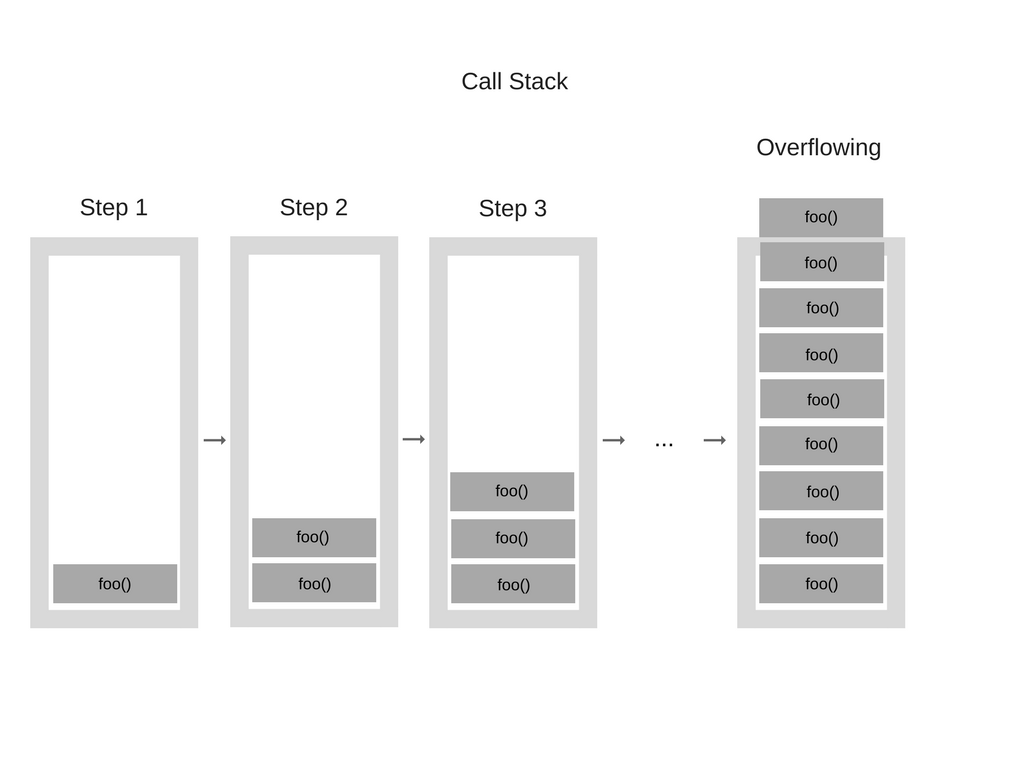

Blowing the stack happens when you reach the maximum Call Stack size. It can happen easily if you're using recursion.

function sayHello(){

sayHello();

}

sayHello();When the engine starts, it will call sayHello, and this function is recursive and starts calling itself without any termination condition, so the call stack looks something like this:

When the number of function calls exceeds the actual size of the call stack, the browser decides to take action by throwing an error like Maximum call stack size exceeded.

The issue is if you have function calls that take a big amount of time to be processed. The browser can't do anything else and it will block the UI or even potentially will stop being responsive after a certain amount of time.

To be able to execute heavy code without blocking the US, we do asynchronous callbacks.

Inlining is the process of replacing a call site with the body of the called function so the optimizations are more meaningful.

Hidden class

JS is a dynamic language which means properties can be easily added or removed after instantiation.

Most JS interpreter use a dictionary-like structure to store the location of object property values in memory. This structures makes retrieving these properties in JS more expensive than in non-dynamic languages.

Since using dictionaries to find the location of properties in memory is inneficient, V8 uses hidden classes. They work similarly to how languages like Java implement storing in memory.

function Point(x,y){

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

var p1 = new Point(1,2);When we call new Point, V8 will create a hidden class called C0 which starts empty.

But when this.x = x is executed, V8 will create a 2nd hidden class called C1 that is based on C0.

C1 describes the location in memory where x can be found. In this case, x is stored at offset 0.

V8 will also update C0 with a class transition to say that if x is added to a point object, the hidden class should switch from C0 to C1.

This step is repeated for this.y = y, a new hidden class called C2 is created and a class transition is added to C1.

An important note is that hidden class transitions are dependent on the order in which properties are added to an object.

function Point(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

var p1 = new Point(1, 2);

p1.a = 5;

p1.b = 6;

var p2 = new Point(3, 4);

p2.b = 7;

p2.a = 8;You could think that for both p1 and p2, the same hidden class and transitions should be used, however, for p1, the first property added is a whereas for p2 it's b.

As a result, p1 and p2 will have different hidden classes. It is then better to initialize dynamic properties in the same order so that hidden classes can be reused.

Inline caching relies on the observation that repeated calls to the same method tend to occur on the same type of object.

V8 keeps a cache of the type of objects that were passed a parameters in recent method calls and uses that to make predictions about the future. If V8 is confident it knows the type of object that will be passed to a method it will bypass the process of figuring out how to access the object's properties and use the stored information from previous lookups to the object's hidden class.

When a method is called on an object, V8 performs a lookup to the hidden class to determine the offset for accessing a specific property. After 2 successful calls of the same method to the same hidden class, V8 omits the hidden class lookup and just adds the offset of the property to the object pointer itself.

Inline caching is also why it's important that objects of the same type share the same hidden class. When instantiating objects, make sure to instantiate its properties in the same order so they can share the same hidden class.

-

Order of object properties: instantiate object properties in the same order so they can share hidden class and code can be optimized.

-

Dynamic properties: Adding properties after instantiation will force a hidden class update. Assign all object properties in the constructor instead to optimise.

-

Methods: Code that executes the same method repeatedly will run faster.

-

Arrays instead of hashes as hashes are more expensive to access.

Memory life cycle is pretty simple:

Allocate Memory --> Use memory --> Release memory

-

Allocate memory: the OS is allocating memory so your program can use it. In languages like C, it is an explicit operation the developer has to handle.

-

Use memory: When your program makes use of the allocated memory.

-

Release memory: release the memory you don't need so it can become available again. Again, in languages like C, this operation has to be explicit.

On hardware level, computer memory is made of a large number of flip-flops that contain transistors able to store 1 bit. Each flip flop is addressable by a unique identifier so we can read and write to them. It is like a giant array of bits.

8 bits are called a byte.

A lot of things are stored in memory:

- Variables and other data used by the program.

- The code, including the OS's code.

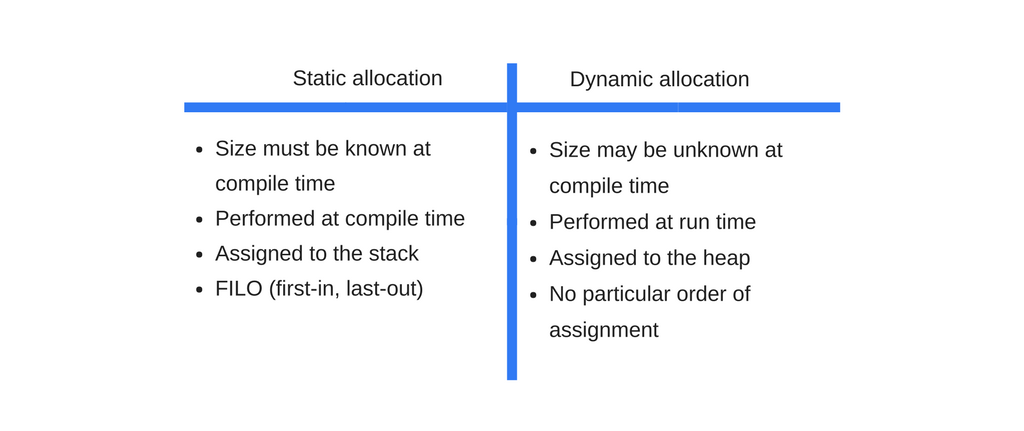

When our code is compiled, the compiler can examine primitive data types and calculate how much memory they will need. The required amount is then allocate to the program in the call stack space.

int n; // 4 bytes

int x[4]; // array of 4 elements, each 4 bytes

double m; // 8 bytes

So we can calculate 4 + 4 * 4 + 8 = 28 bytes.

With dynamic allocation, we don't know at compile time how much memory a variable will need. Therefore, it cannot allocate room for that variable on the stack. Instead, the program needs to ask the OS for the right amount of space at run-time, the memory is assigned from the heap space.

The garbage collector is a piece of software which job is to track memory allocation and find when a piece of memory is no longer needed and will automatically free it. However, this process is an approximation since knowing if a piece of memory is needed is undecidable.

The main concept garbage collection relies on is reference.

An object is a reference to another object if the former has access to the latter.

An object is considered garbage-collectible if there are 0 reference pointing to it.

var x = {

y: {

z: 1

}

}

var a = x; // a has a reference to x.

x = 0; //now the object inside of x has a single reference in a.

var b = a.y; // b has a reference to the object inside of a.

a = 'hello'; // the object inside of x has now 0 reference to it but there is still a reference to y so it cannot be freed.

b = null; // there are now 0 reference to the object y so it can be garbage collected.In the example below, two objects are created and reference each other, hence creating a cycle. After the function f is called, the 2 objects will be out of scope so they could be garbage collected. However, the reference-counting algorithm considers that, as each object references the other one, they cannot be garbage-collected.

function f(){

var a = {}

var a2 = {}

a.b = a2

a2.b = a

return;

}

f()3 steps:

-

Roots: global variables that get referenced in the code. Ex: "window".

-

Algorithms inspect all roots and their children and marks them as active. Anything a root cannot reach is marked as garbage.

-

Garbage collector frees all memory pieces that are not marked as active and returns the memory to the OS.

With the mark and sweep algorithm, cycles are not a problem anymore. After the function call, the 2 objects would be unreachable from the global object so they would be found unreachable by the garbage collector and would then be freed.

Note based on this series of blog posts: https://blog.sessionstack.com/how-javascript-works-memory-management-how-to-handle-4-common-memory-leaks-3f28b94cfbec