This folder contains an example of a REST based API for managing Cars for a Car Sharing software product, based on a production system, that follows many of the principles of Domain Driven Design (DDD) and Clean Architecture/Onion Architecture/Hexagonal Architecture, demonstrates CQRS and has an eventing architecture, using event sourcing for persistence.

It is not a strict implementation of DDD, but something that has many of the ingredients and principles of DDD.

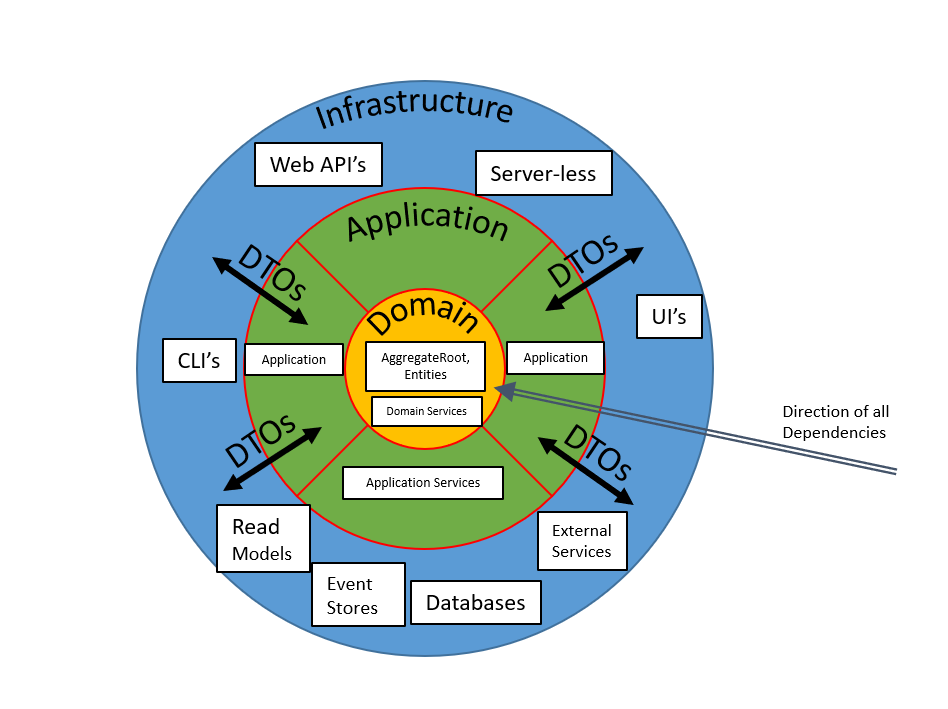

We describe the major boundaries of this RI as either: Infrastructure, Application or Domain.

We use these kinds of terms in this architecture:

- API (REST API),

- Service Operations,

- DTO (Data Transfer Objects),

- REST Resources,

- Application Layer (DDD Application Layer),

- [domain] Entities (DDD Entities), ValueObjects (DDD ValueObject), Aggregates, Domain Services and Repositories

- Commands and Queries, Storage and [data] Entities.

- Events, Read Models and Projections.

In terms of data flow, a typical REST API call results in an interaction like this:

- Messages come in over the wire on HTTP into Service Operations of the API. The API de-serializes the HTTP request into request DTO's that define an application Command or Query.

- The API Service Operations (grouped by REST resource type) then validate the inbound DTO Command, and delegate execution to an appropriate Application Layer. (In this pathway, request DTO's are deconstructed into primitive properties - to save on having another explicit mapping layer).

- The "Application Layer" takes the deconstructed DTO properties, and either instantiates and/or de-hydrates DomainEntities from repositories (via Command Storage), co-ordinates and instructs Entities to do things (Tell-Dont-Ask).

- The domain aggregates and entities make changes to their state by raising events.

- The "Application Layer" uses domain services if necessary, and then re-hydrates the changes of state [events] back to event persistence storage.

- The event persistence triggers the replay of the persisted events, and project the changes onto a read model that stores the latest state of the entity. (to be queried later)

- The Application Layer then converts the changed Entities into DTOs, and hands them back to the API.

- The API layer then serializes the DTO over the wire, and handles the conversion of exceptions to HTTP status codes and status descriptions.

Important: This reference implementation is not part of the QueryAny library/package, just an example of integrating QueryAny in practice.

The RI has tried not to be too strongly opinionated about the layout and naming of files/folders/assemblies on disk, other than to assume that in a small to medium sized product you too would likely split your projects/components into multiple logical, testable layers for maintainability, reuse and future scalability (scale out), as your product grows.

Note: Some of the naming conventions here are debatable and perhaps not to your liking. That's cool too. We have named them in the way we have in this RI, primarily so that you can at a glance understand the intention of them. We would chose a different naming convention in a real product too.

The RI solution demonstrates strict discipline around decoupling and separation of concerns, both of which manage accidental complexity as things change and as the codebase grows. Which should be a primary concern of your codebase.

Design Choice: The RI does does not quite fully implement all GET API patterns that allow clients to have fine grained enough control the data returned on the wire (i.e. embedded resources, filtering etc). So, the inclusion of a GraphQL endpoint is a reasonable thing to need to add to it, or implement a more comprehensive filtering strategy in this API.

Design Choice: There are some pragmatic implementation patterns demonstrated within this RI. Remember that this RI has laid out just one way of doing things. There are many ways of doing the same kind of things, with various design trade offs, especially in the area of Entity/ValueObject mapping and Entity persistence. In the realm of building products, this RI demonstrates prioritization of maintainability over optimal performance. If you are looking for the best way to do things, then you haven't programmed long enough to learn that no such thing exists. Our advice to you is start with something small, and adapt it as you learn more, avoid over-engineering it at all costs. If in doubt, favor what you definitely know you have to work with now, rather than attempting to future proof it. KISS, DRY and YAGNI my friends.

Note: If you don't like what you see here. That's cool, just ignore it. But don't make the mistake of coupling your persistence or your Web API to your domain Entities. That's a fundamental amateur mistake in software engineering, that you are going to make without being very intentional about designing your way out of.

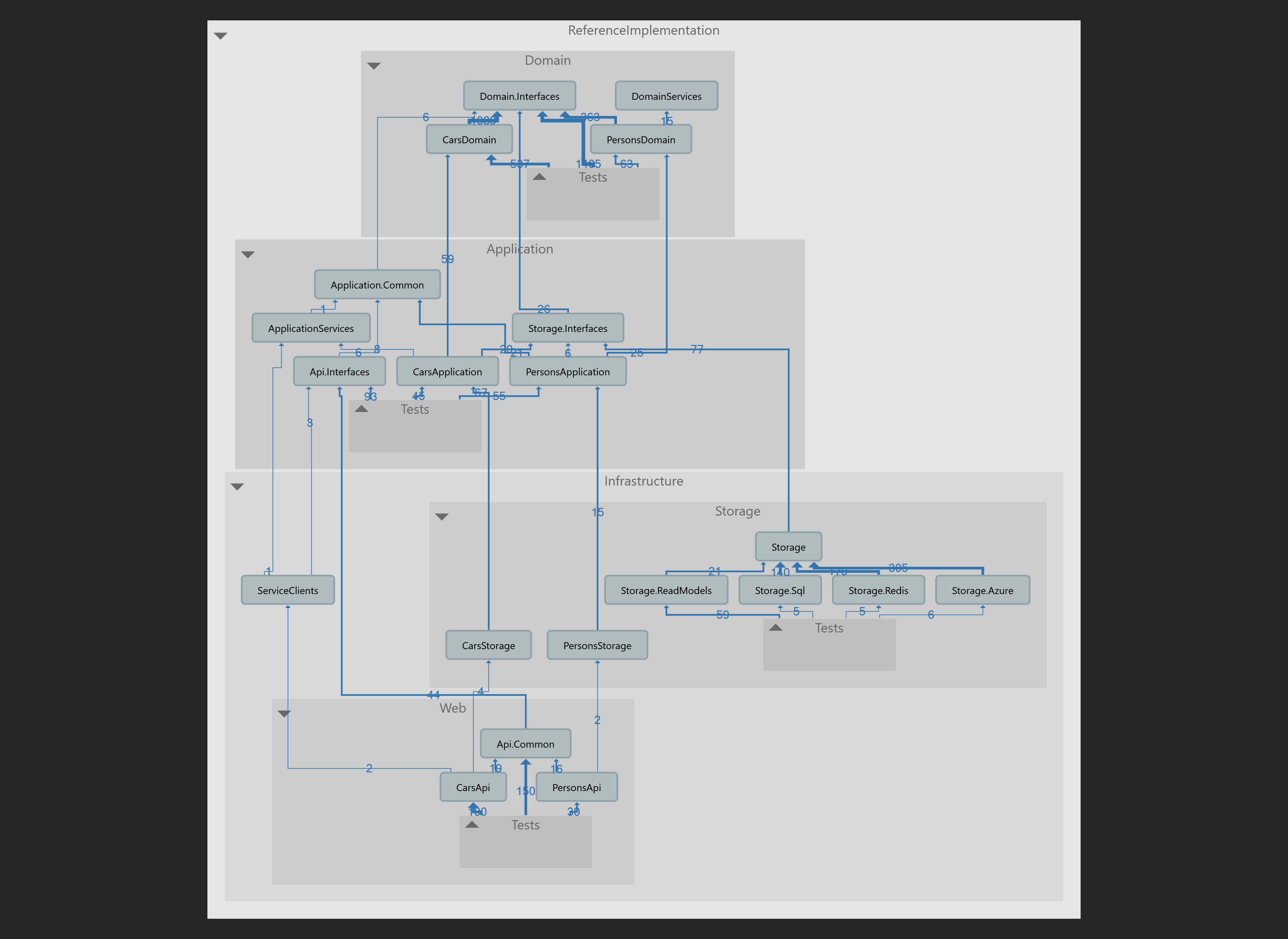

The RI solution is structured into three logical parts:

- Infrastructure - This contains all infrastructure and adapters to that infrastructure (eg. Web API adapters and Storage adapters to repositories)

- Application - this contains your definition of your various application. Applications usually define a set of users and a set of activities that those users can perform. It usually also defines the platform for that application (i.e. Web App, API, Desktop App, Mobile App etc). You may have many apps in your specific domain. Each application layer instantiates and coordinates the domain layer to do stuff. Think commands and queries of CQRS. In the case of building stateless services, this layer would also be responsible for dehydrating and rehydrating domain Entities to and from persistence.

- Domain - core domain classes, and application services unfettered by any concerns of infrastructure and any concerns of the application.

NOTE: There should be no dependency from: classes in Domain -> to classes in Application or from Application to Infrastructure. Ever! All dependencies point towards the domain, and none should point back from domain to application or infrastructure.

The domain layer contains Domain Entities, ValueObjects, Aggregates and Domain Services: Your smart, fully encapsulated, strict OO, 'domain classes' that have all your domain rules, logic, validation, etc encapsulated within them.

Its likely you will have a separate assembly for each domain. Its likely that each domain will contain one or more Aggregate Roots. Its advisable to keep your Aggregate Roots small: for good guidance on this approach see: Effective Aggregate Design - Part I

What the Entities lack is only when to do the things they do in response to the world around them, and who manages their lifecycle (and statelessness). That stimulus will come from the "Application Layer".

Essentially, the core domain logic layer, containing ValueObjects, Entities and Aggregate Roots, and all modelled use cases.

Note: In a real architecture, you would never actually name this layer (or the types within it) using the suffix "Domain" or "Entity". We use it here just as a guide post for you, so that you can tell what the layer contains.

Design Choice: In this case, we have included all the domain Entities for each bounded domain in a separate assembly for simplicity.

Design Choice: The domain Entities in this implementation are relatively simple in terms of functionality and rules (close to anemic due to limited scope of the sample). They also do not display much in the way of traditional OO hierarchical aggregation which is not common and not generally scalable. Usually Aggregate Roots (DDD parlance) like a 'Car' and 'Person' would provide all operations that operate on any aggregated Entities/ValueObjects.

Design Choice: Domain Entities in this RI have been specifically designed to be persistent "aware" for practicality. We use the terms Hydrate/Dehydrate to associate them to persistence support, and we define

Dictionary<string, object>(a.k.a property bags) to remove the need to specify DTO classes for mapping. Which side-steps an additional explicit mapping layer in your code.

Design Choice: There are many ways to handle/decouple persistence between your Entities and repositories, this is one pattern, you may desire another. You definitely don't want your Entities to do their own persistence (like the ActiveRecord pattern does). Persistence is not a concern of your domain. Do could define a mapping layer to DTO's between Entities and repositories (as ORM's do), but having the knowledge of what internal data an Entity needs to be serialized (de-hydrated) and de-serialized (re-hydrated) is knowledge in-practice that an Entity/ValueObject could legitimately have. YMMV, this pattern is absolutely flexible, scalable and simple to maintain.

We anticipate that there will be one of these assemblies for every domain in the product.

Contains shared definitions for use by domain classes, intended to be shared across all domains.

Also intended to be shared to service client libraries (if any).

We anticipate that there will be one of these assemblies for all domains in the product.

If this sample got any larger we might have an assembly for shared code, like primitives etc.

Contains all unit level tests for all components in the architecture, separated by component.

We anticipate that there would probably be a separate test project per assembly to test.

This layer contains the Transaction Scripts/Application Layer/Domain Services: classes that co-ordinate/orchestrate/manage/script your Aggregate Root Entities.

The 'Application Layer' (in DDD parlance) or 'Interactor' (in Clean Architecture parlance) is used to coordinate the various domain Entities and domain services that make up this particular application. Since this later exposes stateless "services", it orchestrates the domain Entities, manages the persistence of them, and all interactions with infrastructure layers (ie. The Web, Persistence, External Services).

These classes contain commands and queries (as in CQRS).

Commands essentially follow the same pattern:

- Retrieve domain Entities from persistence

- Instruct the Entities what they should do now (Tell-Dont-Ask)

- Persist the mutated Entity state again. This layer represents your specific application.

Note: Between your 'transaction scripts/application layer/domain services' and the Infrastructure layer there will always be a mapping (logical or physical) to and from DTO (Data Transfer Objects) or POCO objects. These are bare OO objects with no behaviour in them, that do not use encapsulation (ideally not inheritance), that are the only types that traverse the boundary between Domain<->Infrastructure. The assembly that defines them should contain NO implementation.

Contains the application layer consisting of services that instruct the domain Entities to do things, using the Ask-Dont-Tell pattern.

We anticipate that there will be one of these assemblies for each service you have in your domain.

Contains shared definitions for use by consuming APIs, intended to be shared across all APIs.

We anticipate that there will be one of these assemblies for all APIs in the product.

Contains clients to access external services (relative to each domain). This is the mechanism for cross-domain communication. Usually implemented over HTTP in a distributed system or in-process in a monolithic system.

Contains shared definitions for access to persistence/storage.

Intended to define the interface for implementers of specific storage databases, and repositories.

Contains all unit level tests for all components in the architecture, separated by component.

We anticipate that there would probably be a separate test project per assembly to test.

Contains all Ports & Adapters, all infrastructure classes and anything to do with interacting with the outside world (from the domain's perspective).

This is the web API host. In this case its ASP.NET Core running the ServiceStack framework on Windows. It could be whatever web host you like.

Design Choice: We chose ServiceStack as the foundational web service framework for a few main reasons. (1) it makes defining and configuring services so much easier than Microsoft's WebApi (specifically in areas of extensibility), (2) it includes an

auto-mapperessential for easily maintaining abstractions between service operations, domain Entities and infrastructure layers, and (3) it has excellent reflection support for persisting .Net types that would otherwise be very difficult to persist, causing far more difficulty when it comes to pragmatic persistence.

It defines the HTTP REST endpoints (service operations) and their contracts.

It handles the conversion between HTTP requests <-> Domain Logic. Including: wire-formats, exception mapping, routes, request validation etc.

It contains the ServiceHost class (specific to ServiceStack) which loads all service endpoints, and uses dependency injection for all runtime dependencies.

A host like this one may contain the service operations of one, or more REST resources of any given API. The division of the API into deployment packages will need to remain flexible so that whole APIs can be factored out into separate hosts when the product needs to scale and be optimized.

These are domain specific libraries with repository implementations used in both production code, and during [integration] testing.

Typically, an implementation will have an in-memory class used in integration testing (to increase test speed), and one for (say a database) for use in a production environment - often injected in the ServiceHost of the CarsApi project.

Concrete implementations of IRepository for various storage technologies, and their associated storage abstractions for different persistence patterns. i.e. ICommandStorage<TEntity>, etc

We anticipate that there would probably be a separate project (and nuget package) for each implementation of the

IRepositoryinterface in your architecture. eg. one for SqlServer, one for Redis, one for CosmosDB, etc..

This contains the base classes and interfaces for relaying event changes to read models.

Contains all integration tests for testing the API.

Design Choice: Here we demonstrate testing API's by pre-populating data through the API only. (In practice (not demonstrated here) you may need to have additional API's to load/delete resources for some domains, that would definitely not be shipped in your production distribution) Normally, we would populate the state of the domain through the API itself, and erase all data for each test through the repository we are using in testing. This removes the dependency to know how application data is actually persisted in any repository, since, given the fact that QueryAny is abstracting that knowledge from you in the first place! (since data could be spread across multiple repositories and accessed via various technologies).

Contains integration tests for verifying various repository implementations, against their real repository technology.

These tests have been templatized so that new implementations have a test suite to verify them.

Note: These tests can be slow depending on the repository implementation.

Design Choice: We deliberately chose to use local installations of these repositories rather than cloud based instances. So at this point, you should be able to run all these tests offline.

Contains all unit level tests for all components in the architecture, separated by component.

We anticipate that there would probably be a separate test project per assembly to test.

In this RI we have a number of intentional designs for practical purposes, that reduce the overhead on developers for keeping strictly to pure OO or DDD design principles. These design decisions aim to make the code easy to work with while at the same time maintain high levels of maintainability and decoupling.

This section calls out some of the design principles used behind this reference implementation.

Many of these principles are informed by Domain Driven Design. Many are informed by writing clean testable code that changes frequently.

The application you are choosing to build right now is a different thing than the domain you are choosing to model in software. This subtle distinction makes a large difference to how you design the over architecture. Whilst it is true that you are building both the domain and the application at the same time, it is not true that they are the same thing. For example: You may decide that there are a certain set of users that are going to use this application in a certain way, say a mobile application with limited functionality. Then you are are building a WebApp for another set of users to use a certain way, finally, you build a centralized API that serves both mobile app and web app. In fact you have built 3 applications, but at the heart of it is one logical domain, ideally in one central place to avoid duplication.

For this reason, it is useful to maintain a separation between your domain and the application which is hosting it. We call this an "Application Layer", and it has responsibilities outside the domain for things like persisting stateless interactions, handing commands (like REST API commands), and responding to events in the domain by passing messages through adapters to the outside world.

The Application Layer sits between the Infrastructure layer and the Domain layer. It brokers all interactions to the domain layer through DTO objects. Never exposing domain Entities or their data or their inputs, outside the domain. The domain should never have any dependency on any Application or any Infrastructural component - ever!

In terms of persistence, the Application Layer decides whether to present a stateful or stateless interface to the domain. The domain is not concerned with this. If your application is a web application there are scaling considerations that make stateless a good choice. If you are a desktop application, then its likely a stateful application may be best performing. The choice is entirely up to the application.

It is very useful in terms of availability and load at scale to separate application layers into commands and queries. These benefits are achieved by using CQRS (command query responsibility segregation)

Commands are used to the change the state of domain entities.

Queries are issued to read the state of the domain in its current state.

It is very common with CQRS implementations that the persistence mechanism for the write-side (state change) is different than that of the read-side (querying).

For example: an entity's change of state maybe kept in a transactional log or in an event store, while on the read-side the current state of the domain would be stored in a query-able repository like a relational database.

To help decouple domains (bounded contexts) from each other, and from coupling them together into larger transactional boundaries (violating that boundary), it is useful to use events and notifications between them, rather then direct communication (i.e. a service call).

There are many design tradeoffs in how this is actually implemented.

- In terms of the software to support this decoupling, there is undoubtedly more mapping code and infrastructural code to manage the interactions, than you would have in a synchronous system.

- In terms of whether the coupling is synchronous or asynchronous. The tradeoff- favors availability over consistency when the system is distributed and the mechanism is asynchronous.

In this RI solution, events are persisted to a EventingStorage<TEntity> as an events stream. Events are then relayed to read models to playback the events stream into projections for each of the events to build up a current state.

There are many benefits, including the ability to rebuild the state of any entity from scratch. To create multiple projections better suited the read-side, than the write side. This helps minimize the dependencies inherent in write-side data models long term.

ValueObjects represent most of the data primitives in a domain. Rather than using language primitives (e.g. string, int, decimal, etc.) ValueObjects better describe the data in terms of what it is used for, and encapsulate the behavior and manipulation of the data far better when it comes to manipulating the domain.

They have the property that two instances with the same internal value are in fact equal. (As opposed to Entities, which despite their value, are equal if their Id is equal).

Like Entities, they contain data, and behavior.

Like Entities, they must not exist in the domain in an invalid state at any time.

Unlike Entities, they do not have a unique identifier.

Unlike Entities, they are immutable. That means, once they have been created, they cannot be changed. New instances of them must be created instead, especially if commands change their state.

In practice:

- ValueObjects are often instantiated with their value in their constructor, where those values will be validated to ensure that they don't allow the ValueObject to invalidate the owning Entity.

- ValueObjects will never allow their "value" to be changed, so must not have any public properties or methods to change their internal state.

- ValueObjects will derive from

ValueObjectBase<TValueObject>and they will implement the inherited methods that provide equality and persistence support. - Commands that change the state of a ValueObject must return a new instance of the ValueObject. Since they are immutable.

- You should not expect a caller to know how to change the state of an ValueObject. You should provide a method that validates the value, and any constraints, that would mutate it. So, no public setters.

- ValueObjects support persistence of their internal state through the

IPersistableValueObjectinterface, which is used by persistence layers. A ValueObject never persists itself. Only Application Layers do that. - ValueObjects derive from

ValueObjectBase<TValueObject>, they can have any constructor, they must implement Dehydration/Rehydration, and must have a static, public, parameter-less method calledRehydratethat returns aValueObjectFactory<ValueObjectBase<TValueObject>>used for instantiation by persistence layers.

Example of Rehydrate Method:

public static ValueObjectFactory<Manufacturer> Rehydrate()

{

return (value, container) =>

{

var parts = RehydrateToList(value);

return new Manufacturer(parts[0].ToInt(0), parts[1], parts[2]);

};

}

Note: Entities are not all that common in a domain, most domain concepts are either represented as ValueObjects or as Aggregates.

Entities have the property that two instances of the same type of Entity are equal if their Id is equal. (Irrespective of whether their internal values are equal or not).

Like ValueObjects, they contain data and behavior.

Like ValueObjects, they must not exist in the domain in an invalid state at any time.

Unlike ValueObjects, they have a unique identifier (unique for that type across the whole domain).

Unlike ValueObjects, they are mutable. That means, once they have been created, their internal state can be changed.

In practice:

- Entities are often instantiated with no values in their constructor, and if so, those values will be validated at construction time.

- Entities will permit their state to be changed. You should not expect a caller to know how to change the state of an Entity directly. You should provide a

voidmethod that validates the value, and any constraints, that mutates the Entity itself. So, no public setters. - Commands that change the state of a Entities do not return any value, since they are mutable commands.

- Entities will derive from

EntityBaseand they will implement the inherited methods that provide identification and persistence support. - Entities support persistence of their internal state through the

IPersisableEntityinterface, which is used by persistence layers. An Entity never persists itself. Only Application Layers do that. - Entity identifiers are created by a

IIdentifierFactorywhich generates the ID for the Entity. This is expected to be generated when the Entity is first created. - Entities derive from

EntityBasethey can have any constructor, they must implement Dehydration/Rehydration, and must have a static, public, parameter-less method calledRehydratethat returns aEntityFactory<EntityBase>used for instantiation by persistence layers.

Example of Rehydrate Method:

public static EntityFactory<CarEntity> Rehydrate()

{

return (hydratingProperties, container) => new CarEntity(container.Resolve<IRecorder>(),

new HydrationIdentifierFactory(hydratingProperties));

}

These are Entities which embed child Entities and ValueObjects. They form a transactional and protective boundary around all those children. Such that the Entities and ValueObjects within them are maintained together and they not accessible or referenceable outside the Aggregate.

An Aggregate is any Entity that has child Entities or child ValueObjects.

The top most parent Aggregate is referred to as the Aggregate Root. Each domain will have at least one.

Any action that you need to perform on child Aggregate, Entity or ValueObject must be performed on the Aggregate Root itself. Which means that you cannot access or instruct a child Entity or ValueObject to do anything directly. All operations of anything in the Aggregate must be method calls on the Aggregate Root.

If an Aggregate is removed from the system, so are all of its children Entities.

An aggregate is persisted as a whole at the same time. The aggregate is responsible for enforcing its invariants at all times, so that it and all its children are in a valid state at all times.

In practice:

- Keep Aggregates small, and as best as you can avoid one-to-many child relationships. Try to reference other Entities within the Aggregate by ID, instead of referencing the Entity directly.

- Aggregates are very similar to Entities, so are implemented in a similar way, except that Entities must be able to notify the root of any of their own state changes.

- Aggregates will be required to validate the state of all of its children Entities or ValueObjects at all times.

- Aggregate Roots do not expose the child Entities to the outside world. Expose new methods on the Aggregate Root to execute methods on child Entities/ValueObjects.

- Persist an Aggregate and all their child Entities and ValueObjects at the same time (using separate repositories if necessary).

- Avoid changing other Aggregates from changing any Aggregate directly. Instead, decouple by use events (and eventual consistency) so that other Aggregates in the domain can respond to change events rather than coupling the aggregates together. (This may just mean having a simple synchronous event handling mechanism inside the domain).

- Use domain services to do things that child Entities and ValueObjects don't/can't do normally.

Stateless services that perform services to Entities that would not naturally fit inside of an Entity.

Due to the fact that we are using generic abstractions like ICommandStorage<TEntity> and IQueryStorage<TEntity> to remove coupling from the codebase, and because this strategy entails compromising repository technology specific optimizations; we accept the fact that no repository technology will be used optimally in this reference implementation. They will be used generically.

No abstraction can possibly be optimal for every single repository technology, since all repository technologies aim to satisfy different performance design goals. However, most of these optimizations are not important to you in the early stages of product development.

We accept that fact, and we accept that these lost optimizations are likely not to be important for 80% of the use cases for repositories for persistence for a software product in its early stages.

We also accept that at the time in the software products life when these optimizations may become important, you can simply optimize that usage by engineering in a more optimal implementation for that part of the product. This has the effect of increasing complexity (making that more optimal part of the codebase harder to change in the future).

For those reasons, the following sub-optimizations on specific repository implementations is acceptable:

- A

1000result limit on all queries, in:InProcessInMemRepository,RedisInMemRepository,AzureTableStorageRepository,AzureCosmosSqlApiRepository,SqlServerRepository. - Entities (into memory) from each container, in:

InProcessInMemRepository,RedisInMemRepository. - In memory (Where clause) filtering, in:

InProcessInMemRepository,RedisInMemRepository. - Multiple fetches of individual joined Entities, in:

AzureTableStorageRepository,AzureCosmosSqlApiRepository. - In memory joining of joined Entities, in:

InProcessInMemRepository,RedisInMemRepository,AzureTableStorageRepository,AzureCosmosSqlApiRepository. - In memory ordering, limiting, offsetting, in:

InProcessInMemRepository,RedisInMemRepository,AzureTableStorageRepository.

Ideally, there would be a mapping between domain Entities and DTO's whenever Entities traverse over any boundary. Such as from Infrastructure to Application, and from Application to Domain, and visa-versa.

For example 1: When HTTP requests in a REST API invoke domain Entities to perform work, the data passed into Entities would be in the form of DTO's coming over the wire as JSON. That requires mapping DTO -> Entity and visa versa.

For example 2: When domain Entities are persisted to storage, the Entity would be mapped to a DTO and then passed to a physical repository for persisting to that store. That requires mapping Entity -> DTO and visa versa.

- All these mappings (Entity <-> DTO and visa-versa) require knowledge of those mappings codified somewhere in the code.

- Typically, in the case of inbound invocation (eg. HTTP requests/responses), this mapping is codified outside the Entity in a service operation type.

- Typically, in the case of an outbound invocation (eg. Persistence), this mapping is codified inside the Entity itself or in the Application Layer.

- The mapping code may be complex (depending on the Entity's complexity), and this code may also be hard to maintain correctly. It is often tedious to maintain, difficult to type check and difficult to make cohesive.

For these reasons and some others, we have taken a design shortcut in persistence mapping by making the Entities opt into supporting persistency in a generic way.

Each domain Entity is required to:

- Define a name of a logical collection (i.e. the name of a table, for use by database repository) (See: EntityNameAttribute)

- Define a set of properties (object dictionary) that represents the internal state of the Entity (See: Dehydrate).

- Define a function that can restore the internal state of the Entity from a set of properties (See: Rehydrate).

- Define an Entity factory function that can be called to construct a new instance of the Entity (See: EntityFactory).

With this Entity policy in effect, domain Entities can maintain their full OO behaviors and encapsulation whilst participating in persistence schemes, like the one implemented in this RI. Which is typically very hard to design for most developers.

Note: Again, this is one strategy, there are many.

In this reference implementation we utilize a custom event store in any of the IRepository implementations.

This is possible if we just use 2 simple tables. One for the event streams and one for the checkpoints.

When Events are saved they are currently saved to a table called: EntityName_Events

- They are saved using the repo tech that is configured in

IEventStreamStorage. - They are saved to a container called: "{ContainerName}_Events"

where "{ContainerName}" is defined by

TAggregateRootof theIEventStreamStorageinstance

Each saved EventEntity is given:

- the EntityType type name of the Entity

- the EventType type name of the raised Event

- the Id is unique to the event

- the streamName is {EntityName}_{Id}

- where EntityName is defined by TAggregateRoot

- where Id is the id of the entity

Note: this StreamName is unique for every instance of the event

We store this table in the event store, in a table called: "EntityName_Events"

| Id | LastPersistedAtUtc | StreamName | Version | EntityType | EventType | Data | Metadata |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ev_1234... | DateTime | EntityName_en_1234.... | 1 | EntityType | EventType | {eventasjson} | {"Fqn":"EventType, FQN"} |

- First: Getting Started for details on what you need installed on your machine.

- Build the solution.

- Run all tests in the solution.

Note: if the integration tests for one of the repositories fail, its likely due to the fact that you don't have that technology installed on your local machine, or that you are not running your IDE as Administrator, and therefore cant start/stop those local services. Refer to step 1 above.

- First: Getting Started for details on what you need installed on your machine.

- You will need to start the Azure CosmosDB emulator on your machine (from the Start Menu).

- Ensure that you have manually created a new CosmosDB database called:

Production. - Start the

CarsApiandPersonsApiprojects locally with F5. (A browser should open to API documentation site for both sites).

To manually test everything is working, or debug the code:

- Navigate to: GET https://localhost:5001/cars/available (you should get an empty array of cars in response)

- Using a tool like PostMan or other REST client, create a new car by calling:

POST /carswith a JSON body like this:{"Year": 2020,"Make": "Honda","Model": "Civic"}