| theme | transition | highlightTheme |

|---|---|---|

simple |

slide |

vs |

SSID: Internet Backup - C

Password: ShareWithIPFS

note: - So first off, welcome! - In today's workshop we're going to introduce you to a bunch of tools and techniques to facilitate building real-world apps and libraries on top of IPFS. - We're going to do this through the lens of real app development, starting with a simple game of peer-to-peer tag (which is kind of funny, because tag is pretty much p2p to start with, but we'll make it even more so). - We'll use Textile developer tools to do this, and we'll cover several concepts core to the Textile ecosystem, including structured data and schemas, decentralized database handling via threads, identity, contacts, and peers, and a bunch of social interactions such as likes, comments, and sharing.

--

...a set of tools and trust-less infrastructure for building censorship resistant and privacy preserving applications

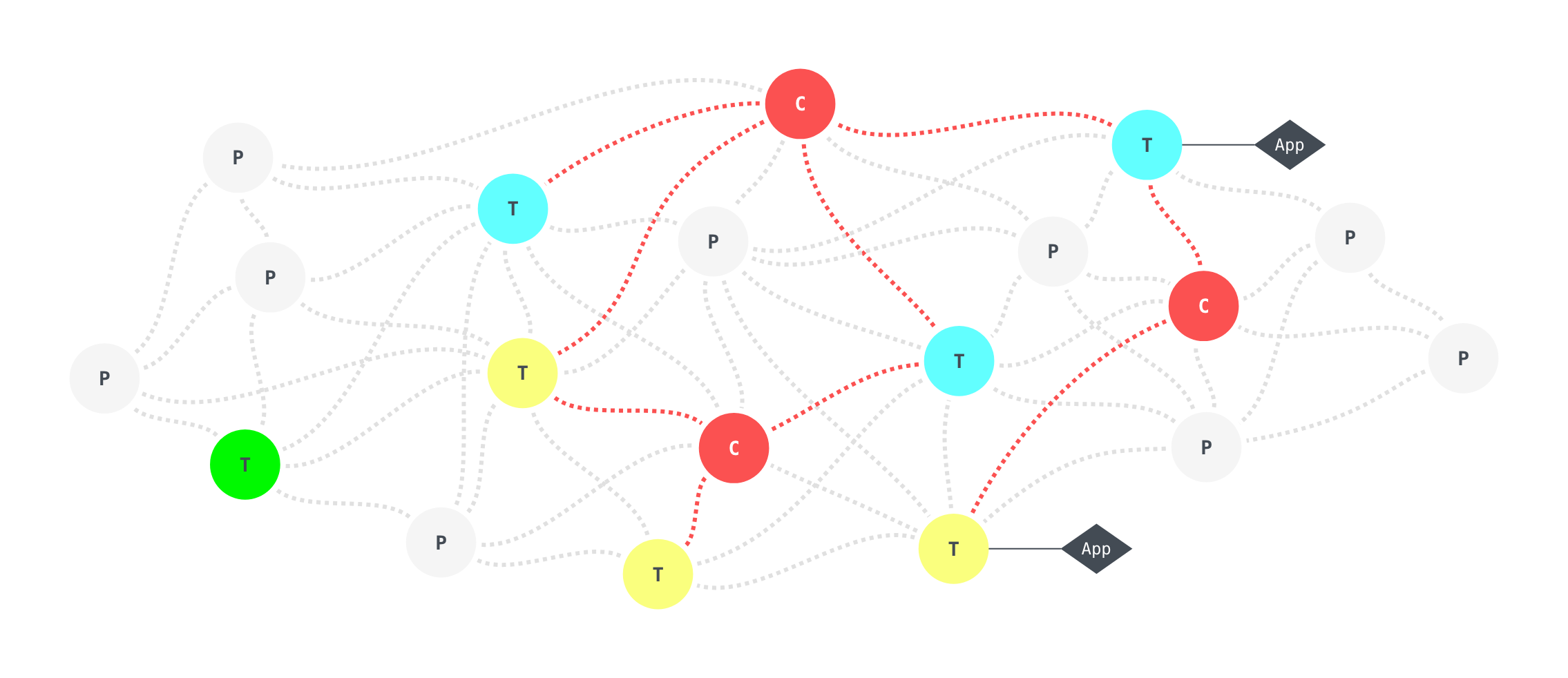

note: - I've already said Textile 3 times, so speaking of Textile... - Textile provides encrypted, recoverable, schema-based, and cross-application data storage built on IPFS and libp2p. - While interoperable with the whole IPFS peer-to-peer network, Textile-flavored peers represent an additional layer or sub-network of users, applications, and services. I've heard it referred to a layer 2 of sorts if you're into that kinda thing. - We've then built a bunch of developer tools on top of that network, which make building cross-platform dapps on IPFS much easier, so that's what we'll be playing with today.

--

Carson | Andrew | Benjamin

Sander | Aaron | Thomas

note: - Our team today includes about half of Textile, so if anything goes wrong during the session, remember that it's the other half's fault, not ours ;) I think the way we're going to do this, is that I'll go through the session with you all, and Andrew and Ben will be available to troubleshoot, answer questions, and correct me when I make mistakes... - I'm Carson Farmer, and I've been with Textile since the start, mostly building tools, writing about IPFS and Textile, developing training materials, and working on our Javascript offerings. I've also written a lot about building tools with IPFS. - And Andrew... - ANd Ben...

- Split into two parts, with break in the middle

- First half is conceptual/theoretical

- Second half is practical

note: - So the outline for today is pretty straight-forward. - We're going to split the session into two parts, with a break in the middle to let you stretch your legs, ask us questions, grab coffee, discretely leave without us noticing, whatever. - The first half is going to be pretty conceptual, and will involve demos, examples, and probably lots of questions. - The second half is going to be much more hands on, we'll get you to install some things, run some command-line tools, play some tag, etc. - We're going to assume some knowledge of IPFS and DWeb concepts in general. Some development experience, though not necessarily mobile or DApps. A working laptop with a modern development setup (Nodejs, React, or even iOS-Xcode would be great). And that's about it. You can sit back and listen, follow along, or even join a group of folks and work together. Whatever your style.

--

- Welcome & Demo

- Anatomy of a game/dapp

- Break & questions

- Hands on fun/command-line

- Wrap-up & hackery

note: - The session will follow this general structure mostly. With a fun demo to start (which some of you might have already been exposed to) - Then we'll explore the anatomy of our IPFS tag dapp, cover some Textile and IPFS-related concepts, then we'll break - After the break, we'll jump into the hands-on component - Here's where you'll actually start to see how things like structured data, threads, p2p communication, etc is used to enhance the user experience. - I'd like to leave plenty of time at the end to hack around and break things, and maybe demo some Javascript code for those who are interested. So let's see where we get. - By the end of the session, if we're done our job, and you've done yours, we'll have a) dissected a working dapp b) explored its underlying infrastructure, and c) maybe even written a few lines of code. - We'll also touch on mobile app development a little bit, but ultimately 1hr is only enough time to give you a taste of building dapps with Textile and IPFS.

note:

- Ok, demo time... Andrew, take it away...

What does it take to build a Game of Tag on IPFS using decentralized data, content addressing, and encrypted communication?

note: - What does it take to build a Game of Tag on IPFS using decentralized data, content addressing, and encrypted communication?

--

- A group of individuals,

- Agreeing on a set of rules,

- With a shared record or state, and

- A way to communicate & verify game play

note: - So, a game of tag is really no more than a group of individuals, who have all agreed on a set of rules for the game, with a shared record or state, and a way to communicate & verify game play as the game progresses. - Its quite a simple example, but it maps really nicely onto p2p interactions, so let's break it down a bit.

--

- Identifying individuals done via data wallets & accounts

- Rules defined using schemas

- Shared record & communication done via threads

- Game environment provided via client libraries

- Today we’ll play with cmdline

note: - How might we do IPFS Tag using Textile? Well here are a few core concepts that we'll cover today to help make our IPFS game of Tag: - Identifying individuals is done via data wallets & accounts, - Rules are defined using something we call schemas (which are a lot like the schemas you're thinking of) - A shared record or game state, and communication of said state will be handled using Textile's threads, which are essentially decentralized database tables, - And we will interface with the game environment via our command-line client library, although we'll show examples of our mobile, and javascript clients as well.

--

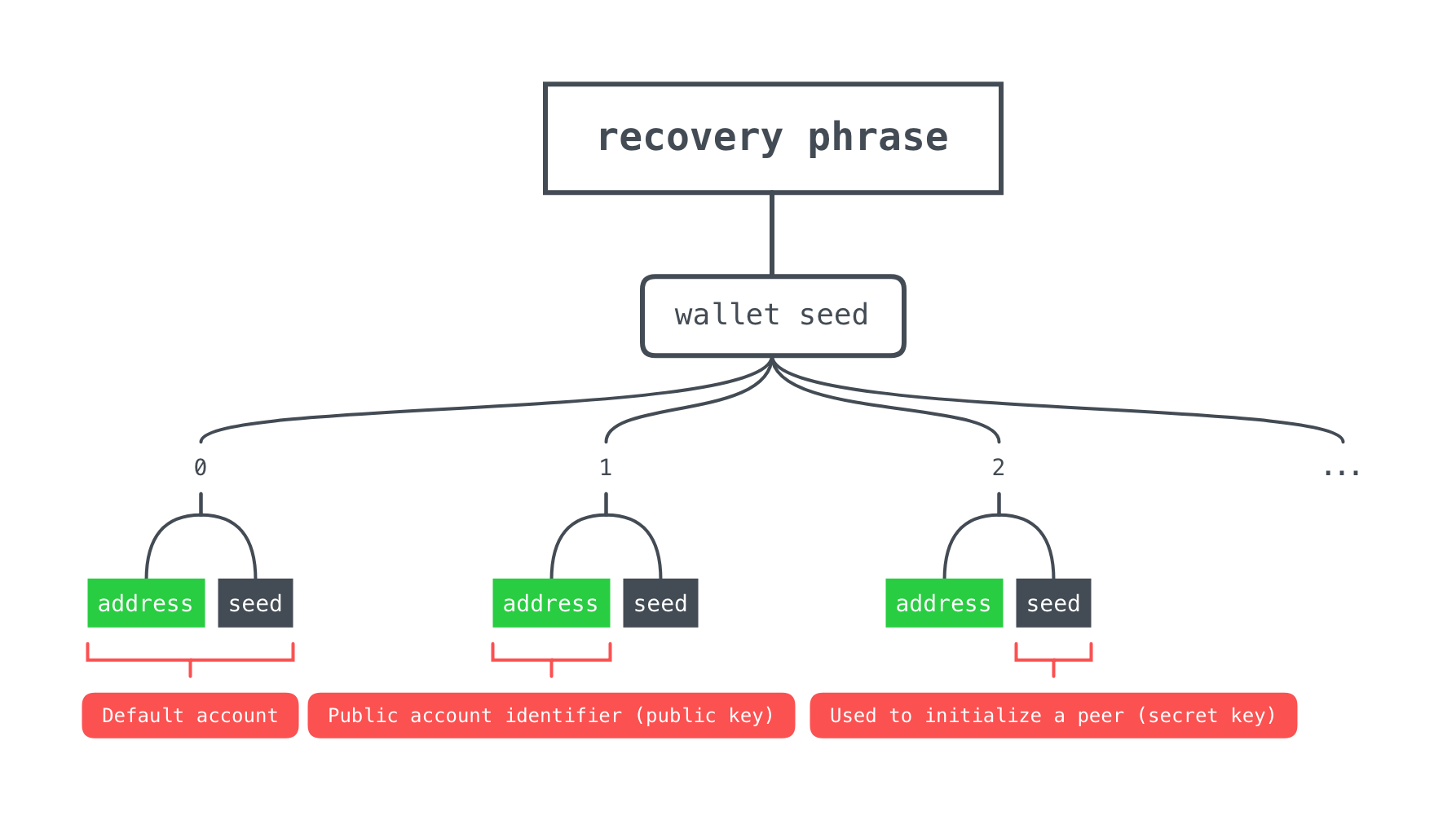

note: - Textile uses a hierarchical deterministic (HD) wallet to derive account keys from a set of unique words, called a mnemonic phrase. - Every account seed "inside" the wallet can be derived from this mnemonic phrase. Meaning that the wallet effectively is the mnemonic phrase. Any given wallet may create an arbitrary number of accounts. For example, a single wallet can be used to provision multiple Textile Photos "accounts", each with a completely different persona. This provides a powerful partitioning framework. - Textile account seeds (private keys) always start with an "S" for "secret" and account addresses (public keys) always start with a "P" for "public". - The actual implementation is a BIP32 Hierarchical Deterministic Wallet based on Stellar's implementation of SLIP-0010. - Account seeds and their public addresses are generated via the wallet pass-phrase. Textile uses ed25519 keys, which is public-key signature system with several attractive features like fast key generation, signing, and verification. These properties become important on less powerful devices like phones. - Account seeds are used to provision new Textile peers. For example, a mobile peer, a desktop peer (like we'll be doing today), etc. Individual peers are tied to a single IPFS instance. - Peers that are backed by the same account are called account peers. Account peers will automatically stay in sync. They are able to instruct one another to create and delete threads. Additionally, they will continuously search the network for each other's encrypted thread snapshots (metadata and the latest update hash, usually stored by cafes). - Accounts can also have profiles, like any standard web 2.0 account. These profiles are self-sovereign, and can include an avatar, display name, and soon even externally verified credentials.

--

- Decentralized database layer that supports...

- Replication (who’s it?)

- p2p updates (tag you’re it!)

- Conflict resolution (no, you’re it!)

- Queries (wait, who's it?)

- Access controls (can I play too?)

- Offline edits, and more...

note: - Textile's 'Threads' are the backbone of Textile's encrypted, recoverable, schema-based, and cross-application data storage. - Think of a thread as a decentralized database of encrypted files and messages, shared between specific participants. - For our purposes, Threads provide replication (who's it?), p2p updates (tag you're it), conflict resolution (no you're it), queries (wait, who's it?), access controls (hey folks, can i play too), offline edits, and more...

--

note: - At the core of every thread is a secret. Only peers that possess the secret can decrypt thread content or follow linkages. - Unlike a blockchain, threads are not based around the idea of consensus. Instead, they follow an agent-centric approach similar to holochain. Each peer has authority over thread access-control and storage. - Because threads are simply a hash-chain of update messages, or blocks, they can represent any type of dataset. Some blocks point to off-chain data stored on IPFS. For example, a set of photos, a PDF, or even a tag event. - Application developers are able to add structure to threads and make them interoperable with other applications by using schemas (more on this in a bit). - Threads are auto-magically synced with other account peers. For example, you may have one peer on your phone, and another on your laptop, both with access to the same account seed (which we talked about earlier). - Threads can also be shared with other non-account peers (other users). - In each case, each peer maintains a copy of its threads. A p2p messaging protocol keeps all the copies in sync. - The special hash-chain or graph structure of a thread allows them to be easily shared with other peers and backed-up to cafes. Given one message, you can find all the others.

--

note: - Control over thread access and sharing is handled by a combination of the type and sharing settings. - An immutable member address "whitelist" gives the initiator fine-grained control. An empty whitelist is taken to be "everyone", which is the default. - Threads also support general access control in the form of 'private', 'read-only', 'public', and 'open' threads. - Similarly, inviting new members to a thread can be controlled via sharing control, with options for 'not sharable', 'invite only', or 'shared'. - We're actually in the process of revamping our access control settings to feel more like web 2.0 style settings - Fun fact, part of the design for our new access controls came from collaborating with the Permaweb.io folks.

--

- Thread

- Backed by its own Keypair

- Array of immutable blocks

- Block

- Metadata + Content

- Types

- Joins, Leaves, Data, Messages, etc.

- Locally indexed

- Exposed via API + SDKs

note: - So I mentioned a chain of events or blocks earlier. - Blocks are the raw components of a thread. Think of them as an append-only log of thread updates where each one is hash-linked to its parent(s), forming a tree. - New / recovering peers can sync history by merely traversing the hash tree. - In practice, blocks are small (encrypted) protocol buffers, linked together by their IPFS CID (content id or hash). There are several block types: including blocks for files, messages, thread invites, liking, leaving a thread, etc. - The orchestration of thread state between peers can be thought of as syncing a graph of blocks and files, which involves sending outbound updates and reading inbound updates. In practice, this is handled by a custom libp2p service.

--

note: - Any data added to a thread ends up as a file. Most of the time, a schema is used to define one or more types of data in a thread such that other users and applications can understand it. - Thread data is built into an IPLD merkle DAG structure (similar to a merkle tree) and stored separately from update blocks on IPFS. A FILES block points to the top-level hash of a file's DAG node. The actual structure of files DAG nodes are determined by, and validated against, a schema, which is where our game gets it's rules...

--

- Two main functions

- Define a Thread's data DAG structure

- Define the order of mills (transforms) needed to produce this structure

note: - A thread can have only one schema. A thread schema has two main functions: - Define a Thread's data DAG structure - Define the order of mills (transforms) needed to produce this structure from the input - To illustrate these functions, take a look at the builtin media schema.

--

// Schema definition (for media in Textile Photos)

{

"name": "media",

"pin": true,

"links": {

"large": {

"use": ":file",

"mill": "/image/resize",

"opts": {

"width": "800",

"quality": "80"

}

},

"small": {

"use": ":file",

"mill": "/image/resize",

"opts": {

"width": "320",

"quality": "80"

}

},

"thumb": {

"use": "large",

"pin": true,

"mill": "/image/resize",

"opts": {

"width": "100",

"quality": "80"

}

}

}

}note: - Each link (large, small, thumb) produces a resized and encrypted image by leveraging the image/resize mill. - Notice that the thumb link uses the large as input. This means that large will need to milled (that's what we call a transform function) before thumb. - Once you understand how schemas and mills work, you can design complex workflows and structures for your applications.

--

Decentralized compute

- Three distinct purposes

- Validate

- Transform

- Index

note: - The meta and content node pairs in a files DAG (which we'll see in a moment) are generated by file mills. - Mills serve three distinct purposes: - Validate the input against accepted media types. The JSON mill will also validate the input against a JSON Schema. - Transform the input data, e.g., encode, resample, encrypt, etc. - Index a metadata object (JSON) describing the transformed output. This allows thread content to be efficiently queried and provides a mechanism for de-duplicating encrypted data.

--

note: - In addition to the transformed bytes, a mill will produce a file metadata object for every input. - File metadata objects are what most applications will interact with. They are the objects listed by the Files and Feed APIs. These objects are also used internally for various functions. For example, because good encryption is not deterministic, an input's checksum is used to de-duplicate encrypted data. - So, adding data to a thread results in a DAG defined by a schema. But how exactly is the data stored so as to be programmatically accessible to thread consumers? Let's take a closer look at the DAG produced by the builtin media schema... - Note that a files target is by default a directory of indexes (0, 1, etc.). This means that you can add an entire folder of images (or whatever your data is) with a single update. - Also, each link (large, small, etc.) will always have the special meta and content sub-links, which correspond to the (usually encrypted) file metadata and content.

--

{

"links": {

"large": {

"mill": "/image/resize",

"checksum": "EqkWwbMQoSosYnu85XHpdTsM3NDKTRPk5j4RQjN6c4FZ",

"source": "D4QdxGCAFnGwCHAQxrros1V6zEf78N4ugK3GwZyT5dTJ",

"opts": "21uBAuSeQUdw5aDu5CYPxEfeiLVeuvku1T26nWtJC84C",

"hash": "QmcvoHe333KRf3tfNKrtrM7aMUVnrB4b1JyzhSFybepvqQ",

"key": "6cCnusZVHwp6udnKv3eYhurHK6ArJyFxCYRWTUFG8ZuMwSDwVbis9FUX3GRs",

"media": "image/jpeg",

"name": "clyde.jpg",

"size": "84222",

"added": "2019-03-17T01:20:17.061749Z",

"meta": {

"height": 600,

"width": 800

},

"targets": [

"QmPngweFQ9VUhjtyy8nfJRZ8us9UFbS6Y2trwmAswfJ2yk"

]

},

"small": {

"mill": "/image/resize",

"checksum": "7Gu5s6sZkwU8UQWwJNnJSrVY75ZkQG4bpQSwQPwkk8aX",

"source": "D4QdxGCAFnGwCHAQxrros1V6zEf78N4ugK3GwZyT5dTJ",

"opts": "CassDcqf192MnceweJKGJvhZfrV9kB3GJRbvNPWm6raa",

"hash": "QmZuD522rQiFE2GdbNXvzcQ3Ci6aLvvJtWz52a97iEDy9G",

"key": "29ce4pg64Lj78GuTauQDxeqpfdNCF7fNsJauS552wfpkEjegq8kQgwiNAzJQZ",

"media": "image/jpeg",

"name": "clyde.jpg",

"size": "18145",

"added": "2019-03-17T01:20:14.739531Z",

"meta": {

"height": 240,

"width": 320

},

"targets": [

"QmPngweFQ9VUhjtyy8nfJRZ8us9UFbS6Y2trwmAswfJ2yk"

]

},

"thumb": {

"mill": "/image/resize",

"checksum": "GzB1CWKkKQ5sWS8qQXDoBZxsfFgsgZwD9Z51qX5d7LGW",

"source": "EqkWwbMQoSosYnu85XHpdTsM3NDKTRPk5j4RQjN6c4FZ",

"opts": "7aGVJ7nGgmHdqv8oiEKZ2ZbrNBv1zVP3ADSuT2sW3MwT",

"hash": "QmUuXPhrtLJUzfuoJu7BkfiB2mGfKwq4ExTTF8gVUvAh2U",

"key": "KfW8nTEZqh1NbAcmB51DMaooe34ujucx2DMqBwiz4xs9sDVhNDYNPratgtbf",

"media": "image/jpeg",

"name": "clyde.jpg",

"size": "2979",

"added": "2019-03-17T01:20:17.133863Z",

"meta": {

"height": 75,

"width": 100

},

"targets": [

"QmPngweFQ9VUhjtyy8nfJRZ8us9UFbS6Y2trwmAswfJ2yk"

]

}

}

}note: - This is a JSON representation of file indexes from a single image corresponding to say, file 0 from the previous slide. - If a client app requests data about a file target, this is what they'll get.

--

- Schemas

- Threads

- Blocks

- Data

- Blocks

- Threads

note: - Schemas are used to create and validate the structure of thread files, defining their type and purpose for consumers (users and applications). For example, a photos application may create photo-based threads, a health application my create threads with medical records, a tag game may create a thread for tag events, etc. - By treating schemas as first-class citizens, other applications are also able to understand and make use of these threads. We're going to see an example of this a little bit later, where two different apps will leverage the same underlying thread data. - In practice, schemas have three distinct roles: - Provide instructions for how to transform or "mill" an input, e.g., given a photo, create three different sizes and discard the raw input (this is the media schema). - Define whether or not the resulting DAG nodes should be stored (pinned) on account peers. - Validate thread files from other participants, applying the same storage rules as in (2). - The structure of a schema maps closely to the DAG nodes it creates. Highly complex nodes can be specified with dependencies between each link. A peer will automatically sort this 'graph' of dependencies (using topological sorting) into a series of "steps". Each step is handled by a mill.

--

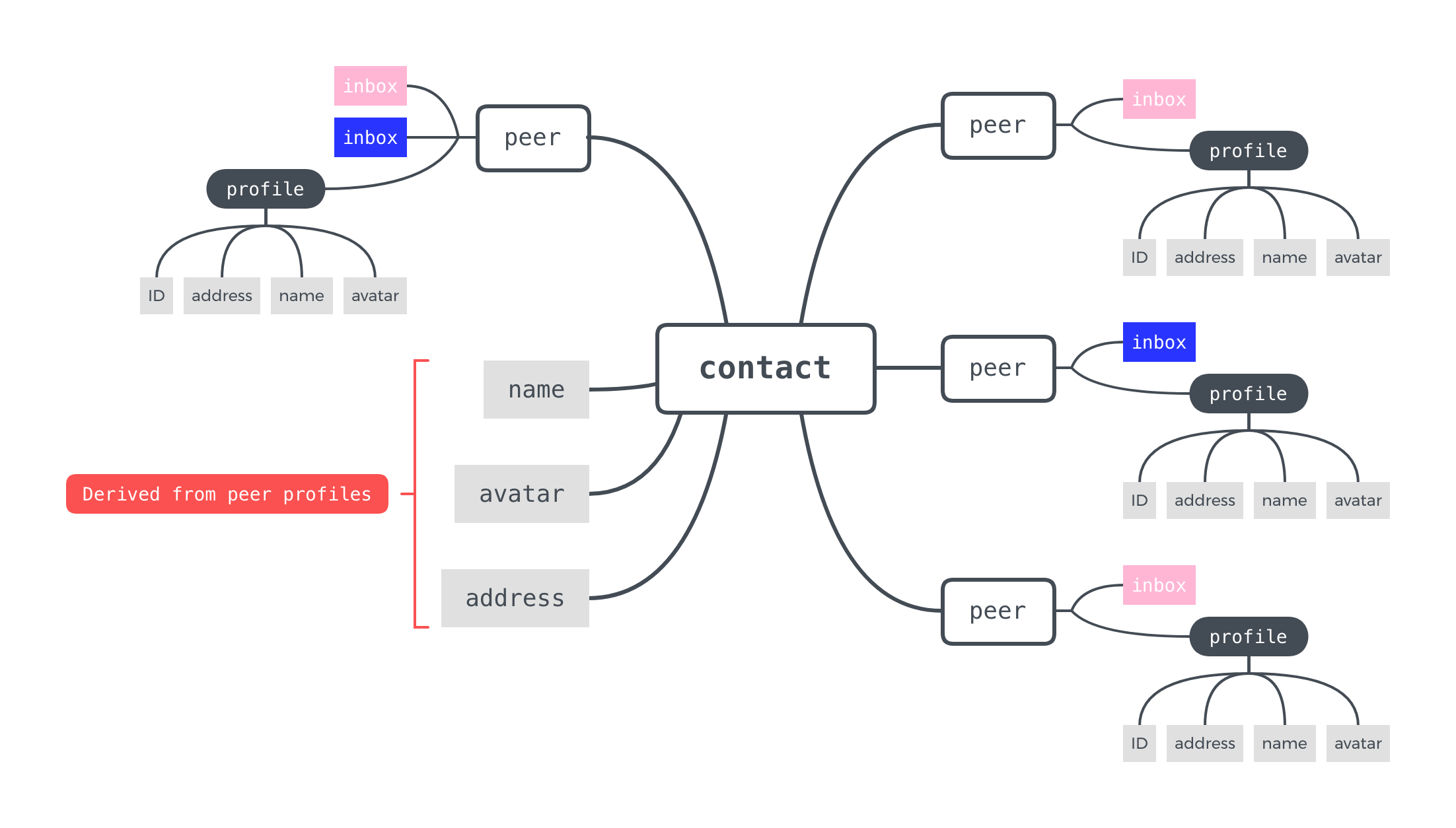

note: - Textile is based around the idea of sharing information between peers. Since this is the case, we need a way to identify and distinguish between different peers or accounts. - As you've already seen, we have the concept of a wallet and account address, which is exactly how we also distinguish between contacts. Textile has taken a pretty agnostic approach to decentralized identity so far, because there are so many folks working in this space. - To date, we haven't focused too much on unique ids, or provable real-world identities, but it is easy to link external identities (say a Keybase ID, or some DiD framework such as such as IDM) to a Textile wallet or account - On that note, over to Ben... - In that vein, a contact can be thought of as a set of ephemeral agents (peers) owned by a single account. That account can have whatever avatar, display name, real-world association that you want. - Each of these peers shares a special private account thread, which tracks account peers, profile information, and known contacts. When indexed, this thread provides: - A "self" contact, much like iOS or other contact systems, which is advertised to the network and indexed for search by registered cafes. - A contact "address book" for interacting with other users. - As shown in the diagram here, a contact will display profile information (name and avatar) from the most recently updated peer. This is pretty powerful, because it means changes made on your mobile device will be automatically reflected on your desktop or in other user's thread information. The network will update changes you make automatically, in an offline-first way. - So for our game of tag, we'll use contact information to invite new users to our game, or join existing games ourselves.

--

- Groups of ~3-4 by OS, or cats vs dogs, or ...

- What you'll (definitely) need

- A terminal/bash/whatever

go-textilecli tools

- What you'll (maybe) want

- IPFS Tag mobile app

- Node.js +

npmtooling

--

- Download and extract the latest release for your OS and architecture (or use

wgetetc...) - macOS and Linux

- Extract the tarball (manually or via...)

👩💻 tar xvfz go-textile_0.5.0_{os}-amd64.tar.gz- Move

textileanyplace in yourPATH(or via...)

👨💻 ./install

- Windows

- Extract the zip file and move

textile.exeanyplace in yourPATH

- Extract the zip file and move

--

- https://github.com/textileio/ipfs-camp-2019

- Clone the repo

👩💻 git clone https://github.com/textileio/ipfs-camp-2019

👨💻 cd ipfs-camp-2019

- Get ready to play around...

--

👩💻 textile wallet create--------------------------------------------------------

| xxxx xxxx xxx xxx xxxx xxxx xxx xxx xxx xxxx xxx xxx |

--------------------------------------------------------

WARNING! Store these words above in a safe place!

WARNING! If you lose your words, you will lose access to data in all derived accounts!

WARNING! Anyone who has access to these words can access your wallet accounts!

Use: `wallet accounts` command to inspect more accounts.

--- ACCOUNT 0 ---

Pxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Sxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxnote:

- All desktop and server peers run as a daemon, which contains an embedded IPFS node. Much like the IPFS daemon, the program (textile) ships with a command-line client.

- Assuming you now have textile available on your system, you can run your own peer. But first, we need to create a new wallet.

- As previously mentioned, Textile uses a hierarchical deterministic (HD) wallet to derive account keys from a set of unique words, called a mnemonic phrase.

- You can initialize one of these wallets with the command-line client (this will not persist anything to your filesystem).

- The output contains information about the wallet's first account, or the keys at index 0. Account seeds (private keys) always starts with an "S" for "secret" and account addresses (public keys) always start with a "P" for "public".

- Most users will only be interested in the first account keys, but you can access deeper indexes with the accounts sub-command. You can try textile wallet accounts --help for details on that.

--

👨💻 textile init SxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxInitialized account with address Pxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx👩💻 textile daemongo-textile version: vx.x.x

Repo version: xx

Repo path: /path/to/.textile/repo

API address: 127.0.0.1:40600

Gateway address: 127.0.0.1:5050

System version: amd64/{darwin,linux,windows}

Golang version: go1.12.x

PeerID: 12D3Kxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Account: Pxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxnote:

- Next, use an account seed from your wallet to initialize a new account peer. Here, we just grab the account seed from the first account above

- There are a dozen or so additional options that are available when initializing, you can find them all via textile init --help.

- Anyone familiar with IPFS will recognize the similarities with these steps. Much like ipfs init, textile init creates an IPFS node repository on disk.

- Now that you have initialized as either an account peer or a cafe peer, you can finally start the daemon.

- Again, see textile daemon --help for more options.

- Now your Textile peer is online and ready to start interacting with data on IPFS.

--

👩💻 textile cafe add 12D3KooWGN8VAsPHsHeJtoTbbzsGjs2LTmQZ6wFKvuPich1TYmYY --token=uggU4NcVGFSPchULpa2zG2NRjw2bFzaiJo3BYAgaFyzCUPRLuAgToE3HXPyo{

"access": "xxx",

"cafe": {

"address": "Pxxx",

"api": "v1",

"node": "0.5.3",

"peer": "12D3Kxxx",

"protocol": "/textile/cafe/1.0.0",

"url": "https://us-west-dev.textile.cafe"

},

"exp": "2019-07-26T10:25:19.333555816Z",

"id": "12D3Kxxx",

"refresh": "xxx",

"rexp": "2019-08-23T10:25:19.333555816Z",

"subject": "12D3Kxxx",

"type": "JWT"

}--

👨💻 textile profile get{

"id": "12D3KooWCMVLfMV8uzYpFN38qn2eMs48tAuHdVZdj3aF6nex6zay",

"address": "P8wW5FYs2ANDan2DV8D45XWKtFFYNTMY8RgLCRcQHjyPZe5j",

"created": "2019-04-19T21:44:46.310082Z",

"updated": "2019-04-19T21:44:46.310082Z"

}

👩💻 textile profile set name "Carson"ok

👨💻 textile profile set avatar "path/to/an/image"ok

note:

- Now, with Textile ready, take a look at your peer profile.

- You'll see your id, which is your embedded IPFS node's peer ID, and your address which is your wallet account's address (public key), which can be shared with other account peers or users.

- In addition to these computer readable names, you can set a display name for your peer. Interacting with other users is a lot easier with display names. However, they are not unique on the network.

- Similarly, you can assign your peer a publicly visible avatar image.

- Go ahead and do both of these things now, pick an image you don't mind being public, and a name that will help your peers know who you are when playing tag.

--

👩💻 textile account get{

"address": "Pxxx",

"name": "Carson",

"avatar": "Qmhash",

"peers": [

{

"id": "12D3Kxxx",

"address": "Pxxx",

"name": "Carson",

"avatar": "Qmhash",

"created": "2019-04-19T21:44:46.310082Z",

"updated": "2019-04-20T00:31:34.699845Z"

}

]

}

note:

- Generally speaking, you can think of peers as ephemeral agents owned by your account. You may lose your device and/or need to access your account on a new one.

- All peers have a special private account thread. In addition to avatars, this thread keeps track of your account peers.

- You can take a look at your account any time, and as new peers are added, they'll be reflected here.

- Just one peer so far. This object is actually a contact. We'll come back to contacts later.

- You can also do other things with your account, such as view your account seed, sync your account with the network, etc. See textile account --help for details.

{

"name": "blob",

"pin": true,

"mill": "/blob"

}

note:

- Ok, time to get serious. Let's create a basic thread to start exploring how we'd connect peers within a game of tag.

- A thread can track data if it was created with a schema. The most basic schema is the built-in pass-through, or 'blob' schema, which looks like this.

- If you recall from before the break, thread schemas are DAG schemas that contain steps to create each node. "blob" defines a single top-level DAG node without any links. We'll get to more complex schemas in a moment. The pin key instructs the peer to locally pin the entire DAG node when it's created from the input. And the mill entry defines the function used to process (or "mill") the data on arrival. /blob is a pass-through, meaning that the data comes out untouched.

--

👨💻 textile threads add "Name" --blob --key="ipfs.camp.tag" {

"block_count": 1,

"head": "Qmhash",

"head_block": {

"author": "12D3Kxxx",

"date": "2019-06-14T21:55:44.358843Z",

"id": "Qmhash",

"parents": [],

"thread": "12D3Kxxx",

"type": "JOIN",

"user": {

"address": "Pxxxx",

"name": "carson"

}

},

"id": "12D3Kxxxx",

"initiator": "Pxxxx",

"key": "ipfs.camp.tag",

"name": "Name",

"peer_count": 1,

"schema": "Qmhash",

"schema_node": {

"mill": "/blob",

"name": "blob",

"pin": true

},

"sk": "xxx",

"state": "LOADED",

"whitelist": []

}

note:

- We can create a thread with this schema using the --blob flag. This is about as basic as we can get, a pass-through schema with all the default access controls.

- There are also other built-in schemas that you can use in your own applications, and lots of options to control who can access the data. See textile threads --help for details.

- If you run that command, your output should show some metadata about the thread you just created, with a reference to the "HEAD" (latest) update block. At this point, this is also the only block, which indicates that your peer joined the thread.

--

👩💻 echo "mmm, bytes..." | textile files add <thread-id>{

"block": "Qmhash",

"target": "Qmhash",

"date": "2019-06-14T21:58:14.375745Z",

"user": {

"address": "Pxxx",

"name": "carson"

},

"files": [

{

"file": {

"mill": "/blob",

"checksum": "xxx",

"source": "xxx",

"opts": "xxx",

"hash": "Qmhash",

"key": "xxx",

"media": "text/plain; charset=utf-8",

"name": "stdin",

"size": "14",

"added": "2019-06-14T21:58:13.931503Z",

"meta": {

},

"targets": [

"Qmhash"

]

}

}

],

"comments": [

],

"likes": [

],

"threads": [

"12D3Kxxx"

]

}

note: - Let's add some data to our thread. Be sure to use your own thread ID. We'll start with some basic text data, added as a raw 'blob' of data. - Any data added to a thread ends up as a 'file', regardless of whether or not the source data was an actual file. For example, here we're echoing a string into a thread, which results in a new "file" object containing that string. - What we get back is a new thread 'block', with information about the block itself, who created it, creation date/time, etc. - The 'files' array contains a list of file metadata objects. In this case, a list of one. - File metadata objects are what most applications will interact with. They are the objects listed by the Files and Feed APIs, which we'll talk about in a bit. These objects are also used internally for various functions. For example, because good encryption is not deterministic, an input's checksum is used to de-duplicate encrypted data.

--

👨💻 textile files keys <target-hash>

{

"files": {

"/0/": "xxx"

}

}

note: - Speaking of encryption, unless a schema step specifies "plaintext": true (which we didn't have in our blob schema), the value of meta and content are both encrypted with the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) using their very own symmetric key. We can view the keys for each node in the DAG using the keys command.

--

note: - At this point, it should be clear that adding data to a thread results in a DAG defined by a schema. But how exactly is the data stored so as to be programmatically accessible to thread consumers? Let's take a closer look at the DAG produced by our built-in blob schema... - Note that a files target is by default a directory of indexes (0, 1, etc.). This mean that you can add an entire 'folder' of data (images, tag events, whatever) with a single update. - Also, every schema step will always have the special meta and content sub-links, which correspond to the (usually encrypted) file metadata and content. - In this case, we only have a single 'step', but our built-in media schema (which is what we use in Textile Photos) has a much more complicated structure

--

{

"name": "cmd-line-tag",

"mill": "/json",

"plaintext": true,

"json_schema": {

"title": "CMD Line Tag Mechanics",

"description": "Possible events in cmd line tag.",

"type": "object",

"required": [ "event" ],

"properties": {

"event": {

"type": "string",

"description": "event type identifier"

},

"target": {

"type": "string",

"description": "peer-id of that the event modifies"

},

"extra": {

"type": "string",

"description": "extra information"

}

}

}

}note:

- Ok, so like the real game of tag, our game needs rules, otherwise, its really just a bunch of people running around tapping each other... which is weird.

- So let's go through one more thread use case that demonstrates how to create a custom DAG schema. We'll make use of a custom JSON schema for tracking JSON documents. In this case, our documents will be used to encode 'tag' events.

- To start, make a file called tag.json, with the following content (or use the existing one in the repo you clone earlier).

- Notice the special 'json_schema' key. This is where you can specify the custom JSON-based schema that your thread updates must satisfy. The really cool thing here is that Textile threads support json-schema.org schemas out of the box. So you can specify pretty complicated workflows and required properties, ensuring your app behaves exactly the way you're expecting it to. Validation in done client side, so there's no required intermediate server at any point along the way.

- In this case, we have one required property, event, just to show you some features of json-schema.org. I highly recommend you check it out for more details.

--

👩💻 textile threads add "Tag" --schema-file=/path/to/tag.json --type="open" --sharing="invite_only"{

"block_count": 1,

"id": "12D3Kxxx",

"initiator": "Pxxx",

"key": "xxx",

"name": "Tag",

"peer_count": 1,

"schema": "Qmhash",

"schema_node": {

"json_schema": {

"description": "Possible events in cmd line tag.",

"properties": {

"event": {

"description": "event type identifier",

"type": "string"

},

"extra": {

"description": "extra information",

"type": "string"

},

"target": {

"description": "peer-id of that the event modifies",

"type": "string"

}

},

"required": [

"event"

],

"title": "CMD Line Tag Mechanics",

"type": "object"

},

"mill": "/json",

"name": "cmd-line-tag",

"plaintext": true

},

"sharing": "INVITE_ONLY",

"sk": "xxx",

"state": "LOADED",

"type": "OPEN",

"whitelist": []

}

note: - So to utilize our custom schema, we'll simply create a new thread, this time specifying the custom json document we just created.

--

👨💻 echo '{ "event": "tag", "target": "<address>" }' | textile files add <thread-id>{

"block": "Qmhash",

"target": "Qmhash",

"date": "2019-06-18T17:51:33.424170Z",

"user": {

"address": "Pxxx",

"name": "carson"

},

"files": [

{

"file": {

"mill": "/json",

"checksum": "xxx",

"source": "xxx",

"opts": "xxx",

"hash": "Qmhash",

"media": "application/json",

"size": "75",

"added": "2019-06-18T17:51:33.033629Z",

"meta": {

},

"targets": [

"Qmxxx"

]

}

}

],

"comments": [

],

"likes": [

],

"threads": [

"12D3Kxxx"

]

}

note:

- Now, to actually use our new thread, we simply add some json data... in this case, we'll just echo the JSON data as a string. The Textile cli tool is smart enough to figure that out and add it as a JSON 'file'

- Your peer will validate the input against the thread's schema. The input will also be validated against its embedded JSON schema (schemas within schemas!).

- Upon success, you'll get back a nicely formatted block update.

- You can try adding an update without the event key, which is invalid. This should result in a error (you should see something like - (root): event is required). This is handy, because it means your app peers won't corrupt a thread with invalid data, ever.

--

- Create a peerpad to share thread information

- Use me:

P4YL7j6fGAwA8WUo9vLGEaDDoKUFrcWEZjDYbRXHtfjMzysc

- Invite them directly

👩💻 textile invite create <thread-id> --address=<neighbor-peer-id>

ok

--

- or create external invite

👨💻 textile invites create <thread-id>{ "id": "Qmhash", "inviter": "Pxxx", "key": "xxx" }

note: - Tag is going to be pretty boring if we don't have some friends to play with... Textile has several ways to handle this. - The most useful, is to create an invite to your game thread, and invite other Textile peers. Those other peers can then ‘accept or add’ the invite to join your game, or of course, they could create their own game and corresponding invite. - So let's share our thread with another user. It was created with type, "open", meaning that other members will be able to read thread updates, and add new updates. In other words, our threads will be writable by all members. - Let's try something here, turn to the nearest person or group of people following along, and exchange peer ids. You can email, text, share a piece of paper, use textile photos, or use peerpad, which is an ipfs-based p2p collaboration tool. - Next, let's create a direct p2p invite to invite that peer to our thread. Alternatively, you could create an external thread invite, which would include the thread key by leaving off the address . - This is slightly less secure, in that you need to send along a key, but can be done reasonably safely by using a secure channel such as e2e encrypted chat, encrypted email, or even qr codes a physical proximity. Obviously if you don't care about privacy (for example, its an open thread, then could just post the thread id and key somewhere for everyone to access)

--

👩💻 textile messages add <thread-id> "game on"{

"block": "Qmhash",

"body": "Game on",

"comments": [],

"date": "2019-06-14T21:37:37.053367Z",

"likes": [],

"user": {

"address": "Pxxx",

"name": "carson"

}

}

note: - Our game setting is almost complete, just a few more steps and we'll have a fully working command-line game of tag. - First though, a big part of tag is actually verbal communication. "Na na, you can't catch me!" and other taunts are part of the game. Our p2p tag game is no different. - With Textile, any thread can take a plain text message. We can use these within the game to communicate with each other. - You can even use it after this session to communicate with folks at the conference! - Be sure to replace the thread parameter with the ID of the thread you generated in the last step.

- List thread blocks (

textile thread blocks) - List contacts (

textile contacts list) - (more) messages (

textile messages --help) - (more) data (

textile files --help) - View a feed (

textile feed) - Observe real-time updates (

textile observe) - Get help (

textile <sub command> --help)

note: - And there we have it, our game is basically ready to go. So let's play around with some tag. Here are a few things you can try as you explore the threads you've created. There are lots of useful APIs to explore, all of which are available in all the various sdks and apis that textile offers. - For example, you can produce a 'feed' of events with the feed api, or observe real-time updates to a thread or all threads via the observe api. This makes things like real-time chat or a game of tag easy to monitor and play around with.

Join

👨💻 textile invites accept <invite-id> --key=<invite-key>

Check

👨💻 sh am-i-it.sh <thread-id>

Play

👩💻 sh tag-peer.sh <thread-id> <address>

note: - To facilitate a group game, Andrew has created a set of pre-built command line tools specific to our IPFS tag game. - If you cloned the repo from earlier, you should already have a series of bash scripts that you can use to more easily play tag. - So for fun, why don't we all join a single game of tag, and get going. - You can also grab the mobile version, and join the game we've already started by finding someone already in the game, and having them invite you via the QR code on their game screen. - Tag is a lot more fun as the game gets bigger, so please do join the game!

- If you want to try out the mobile app

- If you want to hack on the mobile app

- If you want to hack on a tag leader-board

cd demo-leaderboard& follow directions

- If you want to play from cli

cd cli& follow directions