WarpWallet is so 2014. Now, Jason Bourne is using Doubleslow and Steghide.

Shortcomings of WarpWallet:

- JavaScript in the browser is inefficient compared with Python

- It requires too little CPU/RAM resources (about 2 seconds when implemented in Python on i3-2100)

- No user interface to change the default settings

- No checksum protection of the salt

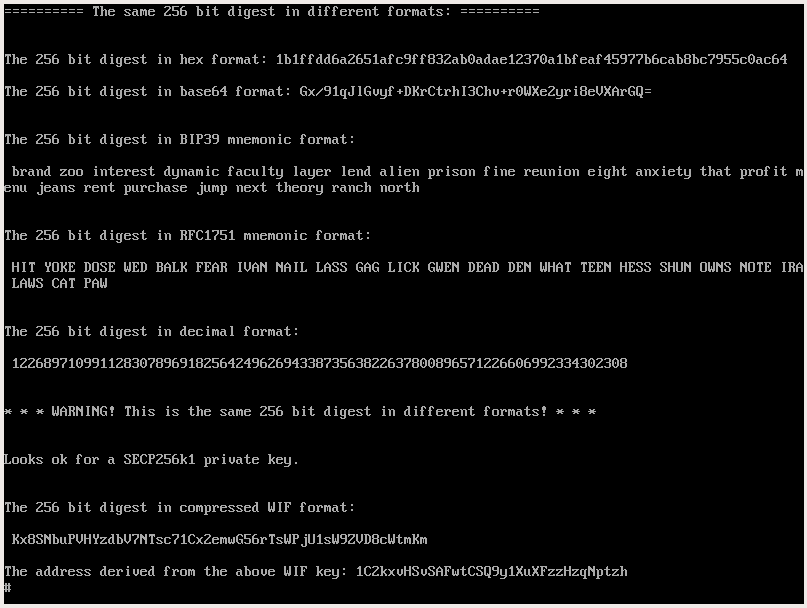

- The result is uncompressed Bitcoin address (it would be better to get BIP39 seed at the output instead, or at least compressed address)

The traditional SHA-256 brainwallet (implemented in Bitaddress) is even worse: it enables the user to avoid using salt, the key stretching is very weak.

- Prevent others from stealing your private keys

- Avoid accidental loss

- Be low-cost

- Be globally accessible

Using programs like Steghide is optional.

First Jason hides the key stretching parameters and multiple seeds (to be used in the future to derive different keys/seeds) with a program like Steghide in a randomly chosen image (img1.jpg).

He uploads that image along with other images to his cloud storage account and other online systems (email accounts) just to be sure that the data is stored safely and globally accessible.

The key stretching scripts can be stored separately (not inside img1.jpg) to minimize the changes to the image (the scripts can be publicly accessible and open source on Github, no need to hide them).

Instead of using Steghide (and remembering another passphrase - the one Steghide uses to encrypt the secrets inside the image) a simple checksum of the image can be used (converted to BIP39, RFC1751, or another format with mnemonic-sha256.py or another script from mnemonic-hashes collection).

One salt/seed can produce multiple wallets (when using different passphrases and key stretching settings).

Jason is using Doubleslow not only to generate BIP39 seeds and keys for cryptocurrencies but also passwords for his VeraCrypt containers. For example, the digest in WIF format can be used as a password for encrypting files (symmetric encryption). Some cryptographic applications may have a password length limit, so the digest in BIP39 format may be too long for them.

Jason uses obscurity only as an additional layer, not as a primary method of achieving security (security through obscurity is a bad practice when obscurity is used alone).

Jason uses secure randomness mixers (Doublerandom) to create a truly random seed/salt and passphrases. The randomness mixers are using entropy from dice, coins, random mouse movements, noise from a microphone or a noise generator, haveged.

The most important element of the system is the key stretching. It must be strong so Jason needs to remember a shorter passphrase (to achieve the same level of security). Jason does not want to risk losing his Bitcoin (or keys for his VeraCrypt container) in case another brain trauma occurs (it would be less likely to forget the shorter passphrase).

The key stretching with the "seed extension" (also known as "extension word" and "passphrase") in the BIP39 specification is very weak (PBKDF2 using 2048 iterations of HMAC-SHA512). This is why it's better to use Doubleslow for a better key stretching.

Jason is choosing a large number of iterations that take half an hour or even several hours on his slightly old computer he uses as an air-gapped computer dedicated to cryptographic stuff. The OS (Cryptopup) is booted from a DVD (or a CD) inserted in a read-only optical device to reduce the risk of hypothetical malware writing the secrets on the optical disk. For the same reason, the computer does not have non-volatile memory devices (hard drive, USB flash drive).

Also, Jason may use Shamir's secret-sharing scheme to give keys to his trusted people so in case he forgets the password he can ask them "Did I gave you some codes for keeping?" (in case he remember who they are).

Unfortunately, it's not possible for a computer to not have non-volatile memory at all (inside the CPU, on the "BIOS/UEFI" memory). But removing some of the devices is protecting at least against the non-sophisticated malware relying on an easily accessible memory (HDD, optical disks in a read-write optical device, USB flash drives).

Jason does not connect the air-gapped computer to other computers after he uses it for cryptographic stuff (in case there is hidden malware inside the BIOS/UEFI, the optical drive's firmware, the CPU).

Jason is keeping his computer in a Faraday cage to reduce the risk of hypothetical malware transmitting data via modulating the signal on the USB cables.

The computer is kept in a room without windows because the hypothetical malware can modulate the light emitted by the HDD LEDs. Or HDD LEDs are disconnected.

The PC speaker is disconnected to reduce the risk of hypothetical malware transmitting secrets via ultrasound.

Jason is using a virtual keyboard when typing passwords to reduce the risk of a hardware keylogger embedded on his keyboard or a keylogger in the BIOS/UEFI.

It's possible to feed the output from Doubleslow to another stage of Doubleslow with the same (or other) key stretching settings and another passphrase. For the next Doubleslow stage Jason may use a mnemonic checksum as a passphrase (generated with a script from the mnemonic-hashes collection from another file - img2.jpg).

But adding more obscurity increases the risk to forget how to repeat the whole procedure.

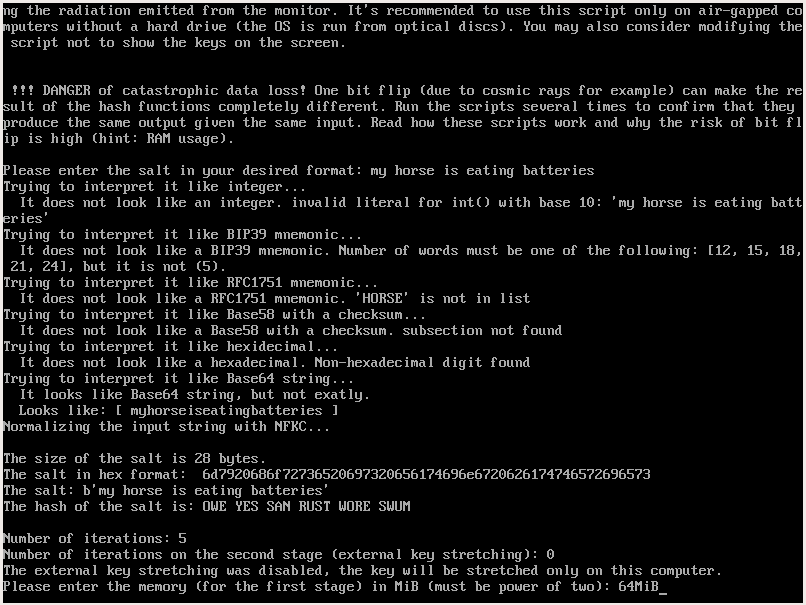

The salt for the Doubleslow can be in different formats, not only formats protected with a checksum:

- RFC1751 mnemonic

- BIP39 mnemonic

- Decimal (big decimal integer)

- Base58 with a checksum

- Hexadecimal

- Base64

- Unicode string (normalized with NFKC by the script)

First, the script tries to parse the salt in the checksum protected formats or as a decimal integer. If no success Doubleslow tries the other formats with priority to parse it as the smallest salt. If the string can be parsed as hexadecimal and base64 the hexadecimal have a priority because the resulting salt is the smallest). If no other format matches Doubleslow is parsing the salt as a Unicode string and then normalizes it with NFKC.

Doubleslow computes the mnemonic hash of the salt, so it's safer to remember it (at least the first two of the words) or write it down, especially when you decide to use a salt in a format not protected with a checksum (arbitrary Unicode string, a decimal integer, base64, hexadecimal). If you notice the checksum does not match - this means you did not enter the salt correctly.

You may use a checksum for the password. However, it is not implemented in Doubleslow because it's a security risk: the attacker can use the checksum to brute-force your password easily (the user may be tempted to write the checksum somewhere - what could go wrong?). It's safe to write (store in your backup) a checksum of your salt, but not the checksum of your password.

Alternatively, you may remember the first two words from the output of Doubleslow. If the words you remember are different, this means you wrote the passphrase wrong, or something other happened (cosmic rays caused bit flip, wrong salt, wrong settings).

For better security, Doubleslow should be modified not to print the derived key (or seed) on the screen. Instead, it would be better to import the seed directly to a wallet like Electrum (by creating a wallet file). Or shield the monitor against surveillance (optical and radio).

Instead of using a USB flash drive, Jason is using only the keyboard and the monitor. To reduce the risk of human i/o errors he is using RFC1751 encoding/decoding.

It's risky to insert USB devices to the air-gapped computer because the hypothetical malware can abuse these devices (by writing data on the hidden areas of the memory - in the areas accessible only by the firmware, in the "unused" space by the filesystem).

For the same reason, it's risky to use floppy disks and to have an optical drive capable of writing. The malware on the online computer can cooperate and upload the secrets to the attacker.

Jason uses an old fashioned camera to photograph the screen in order to make a fast backup of RFC1751 encoded data. He does not use a smartphone (and QR codes) because the hypothetical malware can modulate the light from the monitor in a subtle way nondetectable by humans. And the hypothetical malware inside the smartphone can receive the hidden data and transmit it to the mothership.

- Dangers of using a brainwallet.

- Doubleslow - strong key stretching.

- Doublerandom - randomness mixers.

- Steghide - hiding secrets inside images, audio and video.

- mnemonic-hashes - hashes in different formats: BIP39 mnemonic, RFC1751 mnemonic, hexadecimal, Base64, Base62, Base58Check.

- shamir - a single page tool for splitting secrets into parts or recreating secrets from existing parts.

- Cryptopup - live Linux distribution with crypto tools that fits on a CD (it's only 531MiB).

- Simple White Noise Generator Circuit - this circuit is more clever than other circuits (1, 2) because it's less affected by the noise from the power supply line.