The Semantic DB is an experimental language that borrows the idea of kets, superpositions and operators from quantum mechanics and makes something of a programming language out of it. In its current form it is not a general purpose programming language, but may have relevance in the domain of the semantic web. Our sw files make great little packages of knowledge that are easy to pass around the internet.

The central idea of our language, which we call mumble-lang, is to reduce everything down to kets and operators. Don't be afraid though, no knowledge of quantum mechanics is required to understand mumble! Ket's may initially look strange, but they are really just float, string pairs combined with a few mathematical properties. The advantage of kets is their ability to represent nodes, sets, lists, vectors, superpositions, sequences all with the same notation.

A string, or object, or node in a graph such as "Fred" is simply the ket |Fred>. Likewise, "Sam Roberts" is the ket |Sam Roberts>. Indeed, the so called ket label can be any string that does not contain the | < > characters. But a ket is slightly more general than a string label, it also has an associated coefficient. For example the tuple (3, "apple") in our notation is the ket 3|apple>, which in the context of a shopping list corresponds to 3 apples, naturally enough. While the tuple (0.2, "hungry"), has the corresponding ket 0.2|hungry>, which can be interpreted as 20% hungry, or "a little bit hungry". That is all a ket is, a notation to represent a float, string pair, that looks a little bit like quantum mechanics.

They get more interesting when we build "superpositions" of them, where a superposition is a linear combination of kets. That is, our kets add in a natural way. It is not immediately clear what addition means for tuples of float, string pairs, using kets it is more obvious. For example (3, "apple") + (2, "apple") is not as intuitive as 3|apple> + 2|apple> equals 5|apple>. And (1, "Sam") + (1, "Mary") + (1, "Matt") + (1, "Sarah") is not as concise as |Sam> + |Mary> + |Matt> + |Sarah>.

The power of our superpositions is that they can flexibly represent a variety of things such as:

- "a 50/50 chance of yes or no" as

0.5|yes> + 0.5|no> - "33% chance of 'a', 16% chance of 'b', 48% chance of 'c' and 3% chance of 'd'" as

0.33|a> + 0.16|b> + 0.48|c> + 0.03|d> - The list ["Sam", "Mary", "Matt", "Sarah"] as

|Sam> + |Mary> + |Matt> + |Sarah>. - The set {a,b,c,d,e} as

|a> + |b> + |c> + |d> + |e>. - The vector [0.2, 0.5, 1.7, 9, 3.5] as

0.2|x: 1> + 0.5|x: 2> + 1.7|x: 3> + 9|x: 4> + 3.5|x: 5> - A shopping list such as

3|apple> + |steak> + 5|orange> + |coffee> + |bread> + |milk> + 2|cheese> - A simple equation 3x^2 + 5x + 7 as

3|x*x> + 5|x> + 7| > - "a little bit hungry, very tired, and somewhat upset" as

0.2|hungry> + 0.9|tired> + 0.5|upset> - Or something more abstract such as the superposition:

|a> + 0.5|b> + 2.2|c> + |d>

Briefly we will mention sequences. They are a time ordered sequence of superpositions. For example, "sp1 . sp2 . sp3" represents the time evolution of superpositon sp1, followed by superposition sp2, followed by superposition sp3. For example, the spelling of the name "Fred" or |Fred> is |F> . |r> . |e> . |d>. The first few digits of Pi are |3> . |.> . |1> . |4> . |1> . |5>. And so on. We can represent many things using only superpositions, but sometimes we need a notion of time, or order, and that is when we use sequences. Again though, the fundamental element in a sequence is the ket.

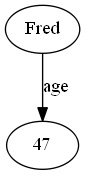

The next component in mumble is the operator. The simplest type of operator is linear, and maps one ket to another ket. If we consider a graph with nodes and directed labelled links between those nodes, then in our notation nodes are kets, and directed links are operators. For example if we have the node |Fred> and the node |47> in a graph, with a directed arrow labelled "age" linking them, then we call "age" an operator. We define an operator using the notation:

age |Fred> => |47>

If that didn't make sense, visually this is:

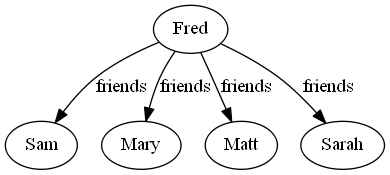

Further, the right hand side can also be a superposition, in this case a list of Fred's friends:

friends |Fred> => |Sam> + |Mary> + |Matt> + |Sarah>

Which visually is this:

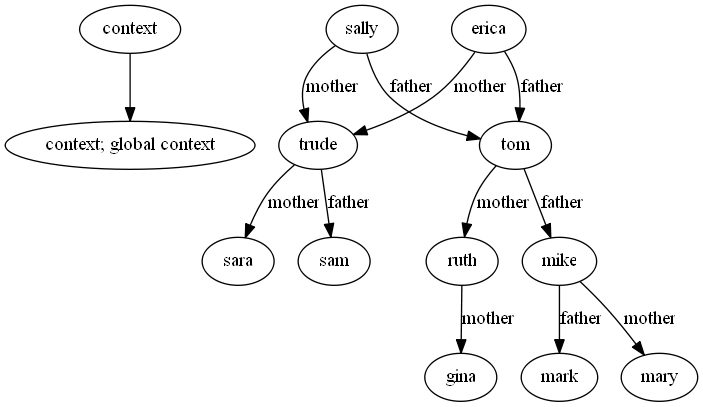

Indeed, this notation is sufficient to represent a simple graph. Consider this knowledge, or collection of "learn rules":

|context> => |context: global context>

mother |sally> => |trude>

father |sally> => |tom>

mother |erica> => |trude>

father |erica> => |tom>

mother |trude> => |sarah>

father |trude> => |sam>

mother |tom> => |ruth>

father |tom> => |mike>

mother |ruth> => |gina>

mother |mike> => |mary>

father |mike> => |mark>

Which directly maps to this graph:

Now we have a little bit of knowledge, what can we do with it? Well, we have a console where we can type in or load .sw files, and then enter queries:

$ ./sdb-console.py

Welcome to version 2.0 of the Semantic DB!

Last updated 8 December, 2018

To load remote sw files, run:

web-files http://semantic-db.org/sw/

To see usage docs, visit:

http://semantic-db.org/docs/usage/

sa:

Let's type in the above learn rules:

sa: mother |sally> => |trude>

sa: father |sally> => |tom>

sa: mother |erica> => |trude>

sa: father |erica> => |tom>

sa: mother |trude> => |sarah>

sa: father |trude> => |sam>

sa: mother |tom> => |ruth>

sa: father |tom> => |mike>

sa: mother |ruth> => |gina>

sa: mother |mike> => |mary>

sa: father |mike> => |mark>

Now "dump" the current context as a check to see what we currently know:

sa: dump

----------------------------------------

|context> => |context: global context>

mother |sally> => |trude>

father |sally> => |tom>

mother |erica> => |trude>

father |erica> => |tom>

mother |trude> => |sarah>

father |trude> => |sam>

mother |tom> => |ruth>

father |tom> => |mike>

mother |ruth> => |gina>

mother |mike> => |mary>

father |mike> => |mark>

----------------------------------------

Now ask who is the father of Erica, and then the mother of Ruth?

sa: father |erica>

|tom>

sa: mother |ruth>

|gina>

Or who is the mother of Sally's father:

sa: mother father |sally>

|ruth>

Or this knowledge all at once in a neatly formatted table:

sa: the-list-of |people> => |sally> + |erica> + |trude> + |tom> + |ruth> + |mike>

sa: table[person, mother, father] the-list-of |people>

+--------+--------+--------+

| person | mother | father |

+--------+--------+--------+

| sally | trude | tom |

| erica | trude | tom |

| trude | sarah | sam |

| tom | ruth | mike |

| ruth | gina | |

| mike | mary | mark |

+--------+--------+--------+

Now we have a couple of comments to make on this. First is the idea of context. It often happens that knowledge changes depending on context, so we needed some way to handle that. And hence the special context learn rule:

|context> => |context: some context>

This defines the context for the learn rules that follow it. And all rules in one context are fully independent of learn rules in all other contexts. Anyway, just a neat way to partition knowledge into domains.

Next comment is that, if you missed it, operators can be composed into operator sequences. An operator sequence is simply a sequence of operators separated by a space. For example we just gave the example of the mother of Sally's father is:

mother father |sally>

Another example might be the question "Who are the friends of the friends of Fred?", in the console would simply be:

sa: friends friends |Fred>

Or "What are the ages of the friends of Fred?", in the console would be:

sa: age friends |Fred>

Or "What are the work-places of the friends of Fred?", in the console would be:

sa: work-place friends |Fred>

Or "What is North, North, North-West of the current location?", in the console would be:

sa: NW N N current |location>

At this point I should expand on my comment above that operators defined by a learn rule are linear (note though that not all operators in mumble are linear). This means that under the cover they are essentially matrices. Indeed, we have the matrix operator that demonstrates this connection. If we consider the above mother/father relations, we can ask the console to display the corresponding matrices:

sa: matrix[mother]

[ gina ] = [ 0 0 1 0 0 0 ] [ erica ]

[ mary ] [ 0 1 0 0 0 0 ] [ mike ]

[ ruth ] [ 0 0 0 0 1 0 ] [ ruth ]

[ sarah ] [ 0 0 0 0 0 1 ] [ sally ]

[ trude ] [ 1 0 0 1 0 0 ] [ tom ]

[ trude ]

sa: matrix[father]

[ mark ] = [ 0 1 0 0 0 ] [ erica ]

[ mike ] [ 0 0 0 1 0 ] [ mike ]

[ sam ] [ 0 0 0 0 1 ] [ sally ]

[ tom ] [ 1 0 1 0 0 ] [ tom ]

[ trude ]

While still in the console, let's demonstrate loading a .sw file. Consider our sw file of plurals. First reset the console back to an empty state:

sa: reset

Warning! This will erase all unsaved work! Are you sure? (y/n): y

Gone ...

Set the sw directory:

sa: cd sw-examples

Now load our knowledge of plurals:

sa: load plural.sw

loading sw file: sw-examples/plural.sw

Now we can ask some questions. "What is the plural of radius?":

sa: plural |radius>

|radii>

"What is the plural of apple?":

sa: plural |apple>

|apples>

"What is the plural of dog?":

sa: plural |dog>

|dogs>

"What is the inverse-plural of mice?":

sa: inverse-plural |mice>

|mouse>

And so on.

The next idea I want to demonstrate is the inherit operator. The idea is that you can define an object to inherit properties from a parent object.

Let's work through a simple example. Consider our favourite cat Trudy, who is so old she lost her teeth, but otherwise is a standard cat. Let's define our context as "Trudy the cat":

sa: |context> => |context: Trudy the cat>

Let's say Trudy is a type of cat:

sa: inherit |trudy> => |cat>

Let's say a cat is a type of feline:

sa: inherit |cat> => |feline>

Further, a feline is a mammal, and a mammal is an animal:

sa: inherit |feline> => |mammal>

sa: inherit |mammal> => |animal>

Now learn some facts about animals, such as they have fur, teeth, 2 eyes and 4 legs:

sa: has-fur |animal> => |yes>

sa: has-teeth |animal> => |yes>

sa: has-2-eyes |animal> => |yes>

sa: has-4-legs |animal> => |yes>

Now learn that feline's have pointy ears:

sa: has-pointy-ears |feline> => |yes>

Finally, learn that Trudy has no teeth:

sa: has-teeth |trudy> => |no>

Now we have entered this, let's dump our current context and see what we now know:

sa: dump

----------------------------------------

|context> => |context: Trudy the cat>

previous |context> => |context: sw console>

inherit |trudy> => |cat>

has-teeth |trudy> => |no>

inherit |cat> => |feline>

inherit |feline> => |mammal>

has-pointy-ears |feline> => |yes>

inherit |mammal> => |animal>

has-fur |animal> => |yes>

has-teeth |animal> => |yes>

has-2-eyes |animal> => |yes>

has-4-legs |animal> => |yes>

----------------------------------------

Now we use the inherit operator to ask a bunch of questions:

Does Trudy have teeth?

Has pointy ears?

Has fur?

Has 2 eyes?

Has 4 legs?

sa: inherit[has-teeth] |trudy>

|no>

sa: inherit[has-pointy-ears] |trudy>

|yes>

sa: inherit[has-fur] |trudy>

|yes>

sa: inherit[has-2-eyes] |trudy>

|yes>

sa: inherit[has-4-legs] |trudy>

|yes>

Which returns the expected answers.

The next component of our project is we have a similarity measure that works with arbitrary superpositions, and is trivally extended to sequences. This measure has the very nice property of returning 1 for identical superpositions, 0 for completely disjoint superpositions, and values in between otherwise. A for example, we can find the similarity of Fred and Sam's friends. Given this knowledge:

sa: friends |Fred> => |Mary> + |Max> + |Rob> + |Eric> + |Liz>

sa: friends |Sam> => |Liz> + |Rob> + |Emma> + |Jane> + |Bella> + |Bill>

We can now ask:

sa: simm( friends |Fred>, friends |Sam> )

0.333|simm>

That is, 33.3% similarity. The power of our simm is that it works with any superposition or sequence.

In this section we put our similarity measure to use, by way of our similar-input[] operator. First, let's generate some data so we can do a worked example, by using the frequencies of female and male names from a US census. Then we use the make-friends.sw file to generate 10 people with 8 random friends each. Here is one result from running:

$ ./sdb-console.py -i sw-examples/female-male-names.sw sw-examples/make-friends.sw

sa: dump rel-kets[friends]

friends |camila> => |kaleigh> + |margarito> + |marietta> + |king> + |fredericka> + |gail> + |carson> + |mertie>

friends |lamar> => |marshall> + |edison> + |marietta> + |leland> + |craig> + |anya> + |danae> + |jaqueline>

friends |latia> => |gail> + |bethann> + |lanette> + |erline> + |keith> + |colette> + |marshall> + |robyn>

friends |craig> => |carmen> + |catina> + |jaime> + |lizzette> + |manual> + |esteban> + |erline> + |lamar>

friends |rudolph> => |barbra> + |luana> + |son> + |solomon> + |luther> + |preston> + |hollis> + |fred>

friends |solomon> => |tasia> + |keith> + |edison> + |kaleigh> + |cristopher> + |marlon> + |preston> + |deloras>

friends |leslie> => |kaleigh> + |chad> + |marshall> + |angle> + |forest> + |edison> + |lita> + |ivelisse>

friends |marietta> => |terrell> + |jaime> + |margarito> + |consuelo> + |jeremy> + |darin> + |fredericka> + |edison>

friends |mertie> => |dee> + |erline> + |chad> + |jordan> + |eddie> + |nigel> + |lupe> + |alex>

friends |luther> => |dorthy> + |vashti> + |king> + |zada> + |fredericka> + |rudolph> + |asa> + |rigoberto>

Now we have this data we can ask who has similar friends to, let's say, Camila? Simply enough:

sa: similar-input[friends] friends |camila>

|camila> + 0.25|marietta> + 0.25|luther> + 0.125|lamar> + 0.125|latia> + 0.125|solomon> + 0.125|leslie>

Or who has similar friends to Craig?

sa: similar-input[friends] friends |craig>

|craig> + 0.125|latia> + 0.125|marietta> + 0.125|mertie>

Or of course in a nice table:

sa: table[person, coeff] 100 similar-input[friends] friends |camila>

+----------+-------+

| person | coeff |

+----------+-------+

| camila | 100 |

| marietta | 25 |

| luther | 25 |

| lamar | 12.5 |

| latia | 12.5 |

| solomon | 12.5 |

| leslie | 12.5 |

+----------+-------+

The general form of our similar-input[] operator is:

similar-input[op] sp

What this does is, it finds all objects that have op defined (in the above case the friends operator), and then compares their right hand side superposition to the input superposition sp (in the above case the input superposition is friends |camila>). Because superpositions are so versatile in representing objects, and because simm works with arbitrary superpositions, or sequences, we in turn can measure similarities of a large variety of objects. All we need is a mapping from an object to a superposition. We could perhaps find similar shopping baskets, similar disease symptoms, similar actors based on what movies they have been, or similar movies based on what actors star in them, and so on.

Here for example are the top 15 actors that have been in movies with Tom Cruise:

+------------------+---------+

| actor | coeff |

+------------------+---------+

| Tom Cruise | 100.000 |

| Nicole Kidman | 11.940 |

| William Mapother | 8.065 |

| Steven Spielberg | 8.065 |

| Ving Rhames | 6.579 |

| Brad Pitt | 6.061 |

| John Travolta | 5.634 |

| Ron (I) Dean | 4.839 |

| Dale Dye | 4.839 |

| Cuba Gooding Jr. | 4.839 |

| Michael G. Kehoe | 4.839 |

| Simon Pegg | 4.839 |

| Sydney Pollack | 4.839 |

| Jeremy Renner | 4.839 |

| George C. Scott | 4.839 |

+------------------+---------+

And here are the top 15 movies that are similar to "Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979)":

+---------------------------------+---------+

| movie | coeff |

+---------------------------------+---------+

| The Motion Picture (1979) | 100.000 |

| The Voyage Home (1986) | 15.625 |

| The Search for Spock (1984) | 15.625 |

| The Undiscovered Country (1991) | 15.625 |

| The Final Frontier (1989) | 10.938 |

| The Wrath of Khan (1982) | 10.938 |

| Road Trek 2011 (2012) | 10.938 |

| Star Trek Adventure (1991) | 10.938 |

| To Be Takei (2014) | 7.812 |

| Generations (1994) | 5.797 |

| Trekkies (1997) | 5.670 |

| Trek Nation (2010) | 4.688 |

| The Other Movie (1981) | 4.688 |

| The Captains (2011) | 4.688 |

| Backyard Blockbusters (2012) | 4.545 |

+---------------------------------+---------+

If-then machines are simple models of neurons that make use of our similarity measure, and our similar-input operator. The core idea is that each if-then machine has a series of patterns, encoded as superpositions, and if any one of them is matched then it "triggers", and outputs a superposition. But because we are using our similarity measure, it is not binary yes/no match, we have degrees of match. That is, our if-then machines are "fuzzy". Indeed, we can dial up or down the fuzzyness by adding in the drop-below[t] operator. If we want 75% match or better we would use drop-below[0.75]. If we want more traditional logic, with 98% match or better, then we would use drop-below[0.98].

The general structure for an if-then machine is:

pattern |node: 1: 1> => sp1

pattern |node: 1: 2> => sp2

pattern |node: 1: 3> => sp3

...

pattern |node: 1: n> => spn

then |node: 1: *> => result-sp

If any of the superpositions {sp1, sp2, sp3, ..., spn} are matched, then the output will be result-sp.

For example, we can encode:

if (A and B and C) then D

if (A or B or C) then E

using two if-then machines:

pattern |node: 1: 1> => |A> + |B> + |C>

then |node: 1: *> => |D>

pattern |node: 2: 1> => |A>

pattern |node: 2: 2> => |B>

pattern |node: 2: 3> => |C>

then |node: 2: *> => |E>

And our corresponding fuzzy if-then operator:

fuzzy-if-then |*> #=> then similar-input[pattern] words-to-list |_self>

And our corresponding strict if-then operator:

strict-if-then |*> #=> drop-below[0.98] then similar-input[pattern] words-to-list |_self>

Which we can display in a table:

sa: table[input, fuzzy-if-then, strict-if-then] (|A> + |B> + |C> + |A and B> + |A and C> + |B and C> + |A, B and C>)

+------------+---------------+----------------+

| input | fuzzy-if-then | strict-if-then |

+------------+---------------+----------------+

| A | E, 0.33 D | E |

| B | E, 0.33 D | E |

| C | E, 0.33 D | E |

| A and B | 0.67 D, E | E |

| A and C | 0.67 D, E | E |

| B and C | 0.67 D, E | E |

| A, B and C | D, E | D, E |

+------------+---------------+----------------+

Note, this is just a toy example for demonstration purposes. With not much work, we can extend it to multiple "layers" of if-then machines. Here is a 2-layer example:

if ((A and B) or (C and D and E) or F) then J

Implemented using these if-then machines:

pattern |node: 1: 1> => |A> + |B>

then |node: 1: *> => |J1>

pattern |node: 2: 1> => |C> + |D> + |E>

then |node: 2: *> => |J2>

pattern |node: 3: 1> => |F>

then |node: 3: *> => |J3>

pattern |node: 4: 1> => |J1>

pattern |node: 4: 2> => |J2>

pattern |node: 4: 3> => |J3>

then |node: 4: *> => |J>

And these operators:

fuzzy-if-then |*> #=> then similar-input[pattern] words-to-list |_self>

fuzzy-if-then-2 |*> #=> (then similar-input[pattern])^2 words-to-list |_self>

strict-if-then |*> #=> drop-below[0.98] then similar-input[pattern] words-to-list |_self>

strict-if-then-2 |*> #=> (drop-below[0.98] then similar-input[pattern])^2 words-to-list |_self>

Producing this table:

sa: table[input, fuzzy-if-then, fuzzy-if-then-2, strict-if-then, strict-if-then-2] (|A> + |B> + |C> + |D> + |E> + |F> + |A and B> + |C and D> + |C and E> + |D and E> + |C, D and E>)

+------------+---------------+-----------------+----------------+------------------+

| input | fuzzy-if-then | fuzzy-if-then-2 | strict-if-then | strict-if-then-2 |

+------------+---------------+-----------------+----------------+------------------+

| A | 0.50 J1 | 0.50 J | | |

| B | 0.50 J1 | 0.50 J | | |

| C | 0.33 J2 | 0.33 J | | |

| D | 0.33 J2 | 0.33 J | | |

| E | 0.33 J2 | 0.33 J | | |

| F | J3 | J | J3 | J |

| A and B | J1 | J | J1 | J |

| C and D | 0.67 J2 | 0.67 J | | |

| C and E | 0.67 J2 | 0.67 J | | |

| D and E | 0.67 J2 | 0.67 J | | |

| C, D and E | J2 | J | J2 | J |

+------------+---------------+-----------------+----------------+------------------+

Anyway, that is just a taste of what is possible with if-then machines.

There is much, much more to mumble, but this will serve as an introduction. The goal of mumble is to be a concise language that contributes towards creating a Giant Global Graph, with nodes passing around, and processing sw files, in a distributed semantic computation. Or more speculatively, a mathematical notation for describing (simple) neural circuits, where the ket label is a label for a neuron or synapse, the coefficient corresponds to the activity of that neuron or synapse over some small time window, superpositions represent the currently active neurons/synapses, and operators change the state of the neural circuit.

- A collection of rules that define plurals and their inverse.

- A collection of rules that define a family tree.

- A collection of rules that can conclude family structures using that family tree.

- Our usage info for the similar-input operator.

- Our usage info for the find-topic operator.

- Our usage info for the predict operator.

- Our worked example for the if-then machine, a simple model of a neuron.

- Our worked example 'active logic' using if-then machines.

- Our worked example 'walking ant'.

- Our current collection of documentation for operators, sw examples, and worked examples.

- they have

|>, the empty ket, or the don't know ket, as the identity element, so that|> + sp == sp + |> == sp, for any superposition sp. - they add.

eg:(3|a> + 0.2|b> + |c>) + (|a> + 0.5|b> + 2.2|c> + |d>) == 4|a> + 0.7|b> + 3.2|c> + |d> - ket's commute, ie the addition is Abelian.

So|a> + |b> + |c> == |b> + |c> + |a> - they can be multiplied by a scalar.

eg:7 (3|a> + 0.2|b> + |c>) == 21|a> + 1.4|b> + 7|c> - you can add a ket with coefficient 0 without changing the "meaning" of a superposition.

eg:meaning(sp1) == meaning(sp1 + 0 sp2)

eg:meaning(3|a> + 2|b> + |c> + 0|x> + 0|y> + 0|z>) == meaning(3|a> + 2|b> + |c>) - we can take the union of them.

eg:union(|a> + 2|b> + 3|c>, 3|a> + 2|b>, |c>) == 3|a> + 2|b> + 3|c> - we can find the intersection.

eg:intersection(|a> + 2|b> + 3|c>, 3|a> + 2|b>, |c>) == |a> + 2|b> + |c>

where union is term by term max of coefficients, and intersection is term by term min of coefficients. - we can find the similarity of them. 1 for identical, 0 for completely different, values in between otherwise.

eg:simm(8|a> + 2.2|b>, 8|a> + 2.2|b>) == |simm>

eg:simm(|b>, |a> + |b> + |c>) == 0.3333|simm>

eg:simm(|a> + |b> + |c>, |x> + |y> + |z>) == 0|simm>