-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 72

New issue

Have a question about this project? Sign up for a free GitHub account to open an issue and contact its maintainers and the community.

By clicking “Sign up for GitHub”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy statement. We’ll occasionally send you account related emails.

Already on GitHub? Sign in to your account

SMS OTP Retriever / SMS verification / Sign up API #152

Comments

|

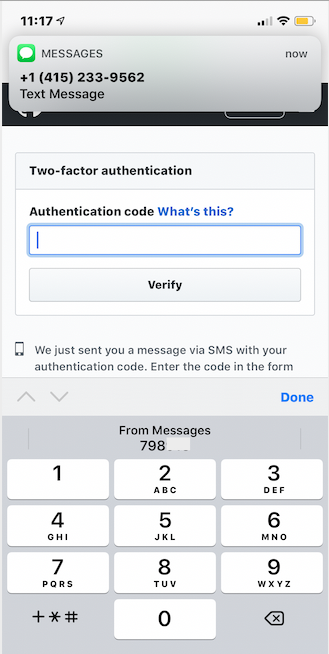

Safari on iOS solves for this without needing an API. If you have an input focused, and you get an SMS, the keyboard automatically finds the code in an SMS and you can just tap it to fill it in. I don't think what's being proposed is bad tho, and maybe would be nice to just have a "otp" autocomplete type for inputs in HTML... but I believe Safari is able to handle this without needing to make any changes to the platform, so I'm not convinced we need a new API for credential management (plus SMS is not very secure). |

|

Our proposal is/was |

|

Awesome! thanks for the pointer @hober. |

|

@marcoscaceres: It might be worth taking a look at the thread in whatwg/html#4586 for some of the rationale behind the more complex approach @samuelgoto, et al. have proposed. |

|

Thanks @mikewest. Will follow along :) |

|

I think whatwg/html#4586 (comment) makes two good points (which I repeat with some of my own interpretation added):

So then there's the question of whether it's better to do this feature 100% in markup (which requires a bit of user intervention to perform the autofill) or whether to make it an API that could be implemented with less user intervention. (The user intervention may, however, be useful as a consent mechanism, and might in fact be the clearest sort of consent mechanism.) |

|

Also cc @mnoorenberghe |

|

Apologies for the late reply, but I tried to break things down into multiple orthogonal dimensions here to help me clarify what I have as a mental model: For example:

It is not entirely clear to me why that might be the case. |

That was my interpretation of what I read in whatwg/html#4586 (comment) |

I tried to clarify this a bit more here, with pointers to the underlying OS APIs:

I don't believe this is the case. I do think that a declarative |

|

Oh, right -- so a declarative API would still be possible, assuming that the constraints on the format of the SMS message were still met. Also, thanks, whatwg/html#4586 (comment) is a useful separation. One other comment from @ekr was the question of whether it's desirable or undesirable that the SMS format be human readable. It seems like an alternative, with different tradeoffs (between phishing and edge-case usability) would be to have an SMS message format that's not human-readable. This (hopefully?) makes it harder to trick a person into pasting the code into a phishing site (or maybe not), but might make edge cases (bad connectivity / timeouts / etc.??) worse. In any case, I'd be interested in opinions from @annevk and @martinthomson as well -- and hopefully we can try to come to some sort of conclusion sooner rather than later. |

|

I like @annevk's comment on the bug, but no matter how true that is, it isn't really a position we can stand on, because SMS OTP is very common and maybe a tiny bit better than not having it. If the goal is to improve usability, this is a fine idea. The model that iOS appears to use is one based on inference. The form field indicates an interest in a OTP. The keyboard (which might reasonably be given access to SMS) is responsible for retrieving codes, not the application itself. Until a code is picked, I hope that the application/site doesn't get any info. The weakness here is that it relies on inference to a high degree. OTP SMS are not regularly formatted in any way because they are designed for humans. And humans being involved is a big part of the fallback story. Yes, we could insist on a new media type for SMS messages that were intended to be routed directly to sites. That could include an origin and a tag, plus maybe even some crypto to ensure that only the origin who wanted the message could get it (whoa!). But that would not be as good as WebAuthn, and it wouldn't even reach everyone. The nice thing with SMS is that I can use the codes on my desktop browser too, even if it doesn't do that SMS forwarding thing that some systems support. Anything we do to make the messages unreadable to humans is going to make those setups worse. So I would say that the inference is basically acceptable. We might improve the situation by providing additional constraints, like the OTP message having to include the name of the server, but it doesn't seem like a good idea to let sites pick a template. I don't think that access to the SMS is entirely necessary, but you could provide a much more limited access if this were the only use case you had in mind. Mike's suggestion to hash or sign the message is an interesting one, but it isn't necessary. You can have the site provide a hash of the message before it asks for it. That proves that it already knows what it was going to send. It's the other type of one-time password. That way, you don't have to worry about polluting messages with gibberish. Think |

|

I don't really have much to add to this since it's not clear to me that we will implement OTP support using SMS and so I haven't looked into the feasibility of implementing such a thing. If we were to help the user with OTP I suspect we would start with more secure solutions first (e.g. TOTP) and by the time that ships SMS OTP usage may be low enough that we won't worry about SMS. |

I suspect y'all have seen https://security.googleblog.com/2019/05/new-research-how-effective-is-basic.html, but the TL;DR is that SMS is, in fact, more than a tiny bit better than nothing. |

|

> TL;DR is that SMS is, in fact, more than a tiny bit better than nothing I read the post. It has six occurences of the phrase "recovery phone number" (not "second factor phone number" which would have been better), and yet no mention of all the published counter-evidence to date of SMS account recovery making things worse for (especially targeted) users. E.g.

Also omitted: the fact that when users turn on SMS 2FA, services in general (e.g. Twitter, Instagram, Paypal, even Apple ID) also enable SMS account recovery, thus making their users more vulnerable to targeted attacks. I have personally known friends (with short / firstname usernames on various services) who have been targeted and had accounts stolen. I think it’s irresponsible to be recommending (or reducing the barriers to) SMS user-flows that default users into SMS account recovery, and especially irresponsible to be pretending it doesn’t exist as a problem by not mentioning it (in particular SIM swaps) despite even the New York Times documenting it almost two years ago, and NIST deprecating it almost three years ago. In addition the "% of users affected" or "% of attacks stopped" metrics are not really good measures here. Steering users to adopt SMS account recovery is the equivalent of planting thousands+ of seeds, for which attackers only have to wait until a few of those accounts grow enough value to be ripe for targeted harvesting. (Originally published at: https://tantek.com/2019/149/t1/) |

That's correct. For third-party iOS apps, only keyboardd (a privileged system process) knows the code until the user activates the keyboard button. The application then receives input event(s) for the code, but can't (modulo timing?) distinguish between the user typing it out themself and using this feature. We're uninterested in pursuing variations on this feature that would expose SMS data to websites.

This is basically how we ended up where we ended up, too. And FWIW, our inference is highly accurate, though I can't quote you any numbers. |

|

@tantek: I see the tradeoffs differently. At scale, we know that just relying on a password is not enough. I think you'd be interested in the detail presented in the papers underlying that blog post, which I think do a good job justifying that assertion: https://ai.google/research/pubs/pub48119 and https://ai.google/research/pubs/pub48117. Still, threat models differ, and you're entirely correct that SIM swapping is a risk that a subset of users will face. We need to offer them better alternatives to SMS. Two points here, though: first, enabling non-SMS 2FA practically requires a recovery flow (which doesn't have to be a phone, to be sure, but the recovery rates with phones for most users is substantially better than, for example, relying on users to print out a list of backup codes). Second, robust 2FA mechanisms like WebAuthn are gaining support, but it's a stretch to expect users to purchase hardware. Some users absolutely should, but we should support those who can't/won't/don't to the extent that we can. @hober: It's not clear to me what you're disapproving of with regard to "expos[ing] SMS data to websites." I think that each of the approaches discussed here assumes that the user is involved in delivering the code to the page (either by poking at a keyboard accessory, or by poking at some other approval UI). With regard to "our inference is highly accurate": are y'all applying any heuristics to decide when to render a given SMS code? e.g. collecting a list of Service A's usual phone numbers, and rendering codes from those numbers only when showing |

You’re glossing over the fact that there is a world of difference between various possible approval UIs. |

Agreed. To be concrete, here is one of the latest formulations (% specific strings to be picked): https://github.com/samuelgoto/sms-receiver/blob/master/README.md#opt-in-ux Can you help me understand which/whether you see substantial privacy properties between that and the autocomplete permission model? For completeness, here is what we had in mind in terms of autocomplete UX: https://github.com/samuelgoto/sms-receiver/blob/master/README.md#autofill-ux

|

|

Based on w3ctag/design-reviews#391 this has changed substantially and is now WebOTP API. |

|

I think we should probably take distinct positions on:

It might make sense to do all of that in this one issue rather than trying to split the discussion across issues. I'd still like to know what Android API can be used to read the SMS messages for this without requesting permission to read all of the user's SMS messages. (I'm concerned about this from the perspective of implementing this in a user-installed browser rather than a system-default browser.) Neither of the APIs described in https://developers.google.com/identity/sms-retriever/choose-an-api seem like they would both work with the currently-described specs (which don't seem to include the necessary app hash for Android's SMS Retriever API) and provide as seamless an experience as browsers that do have permission to read all SMS messages (since Android's SMS User Consent API requires the user pick the particular SMS before sharing it with the app). (I'd note the WebOTP explainer mentions the use of app hashes, but the WebOTP spec doesn't, and neither do either of the other proposals.) (It's also possible there's not as big a difference between pre-installed browsers and user-installed browsers as I think here, in terms of permissions. But there still might be in terms of compatibility, e.g., if sites just start sending Chrome's app hash in all the messages -- or is that something that changes frequently?) Then there are a few other tradeoffs discussed above:

I think WebOTP has stronger anti-phishing but weaker user consent, and |

Ah, totally my fault there, I need to do a better job at keeping the spec up to date. In the meantime, here is the latest formulation we find strikes the right balance so far: WDYT?

We are using the SMS User Consent API, which Android intermediates and asks for the user's permission for the next SMS that looks like one that contains an OTP (heuristics detailed in the documentation).

I don't think there is any distinction being made here between pre-installed browsers and user-installed browsers. Is there a specific one that you believe exists?

Can you expand on this a bit more? I'm failing to see the differences here from a permission perspective: both approaches require user permission before sharing the OTP with the origin. I think there is a distinction in terms of triggering (in that WebOTP allows an origin to trigger an infobar without user action, whereas the autocomplete approach requires the user to focus on the input to augment the keyboard accessory), but not amount of user consent. |

|

Having seen that this is now being shipped in Chrome, it's probably too late for our opinion to have any real impact. However, we should probably close this out more aggressively:

However, there is a bunch of nuance here that is worth drawing out. The reliance on user consent in WebOTP is - as I previously explained - unnecessary and burdensome. An API that did not require active consent would be superior. The origin-bound one-time codes attempts to address this, and is somewhat better for it, but the cost to usability of the SMS message makes it a poor choice and it isn't clear that this creates a strong enough signal for the operating system to release message contents. In terms of ensuring that we align with user intent, the autocomplete option is great, but the usability story is still suboptimal. I think that WebOTP is close, but if the platform supported a means of bypassing the consent dialog by including a hash of the message (maybe salted by the platform in some way, but that increases complexity), then I would happily say that this is |

There isn't anything about the (a) API defined in WebOTP nor (b) the underlying APIs available at the Android level that prevents a browser from bypassing the consent dialog if it chooses to. Specifically, that's where we started from. The SMS is directed to a specific origin via a convention: Which is enough signal for a browser to know whether that SMS should be handed to an origin or not. Chrome moved away from a non-consent UX model to have a consent dialog because there is a belief that that's unveiling information that should be protected under the user's consent (namely, the confirmation that the user owns a specific phone number). That is, the implementation of WebOTP we have so far is under a user consent (and we designed the API such that we could relax that constraint under conditions that the browser feels comfortable with, e.g. maybe past an installation step?), but other browsers should feel free to make other assessments regarding the user's privacy and consent, and there isn't anything about neither the API choices we made nor the underlying OS APIs that prevents you from taking a distance instance.

Does that provide extra clarity? |

|

I'm afraid that doesn't help much. With the structure of the API as proposed, the only real protection the browser offers against reading of arbitrary SMS messages is consent. And consent is terrible. Most of the time this will work as advertised, but then there times when you get a message from a friend while you are waiting for the site to send the OTP. But you are trained to click through, so you do and now some random website receives entirely the wrong message. The API could be a different shape that doesn't require consent AND doesn't impose constraints on the shape of the message. But it would require the API to be a different shape. |

|

then there times when you get a message from a friend while you are

waiting for the site to send the OTP

I don't know how that's possible.

I'm assuming you read the Android API behavior (which doesn't hand out any

SMS from your contacts list) AND the SMS formatting convention (which is

designed to be something unlikely for humans to construct)?

…On Thu, Jun 18, 2020, 8:53 PM Martin Thomson ***@***.***> wrote:

I'm afraid that doesn't help much.

With the structure of the API as proposed, the only real protection the

browser offers against reading of arbitrary SMS messages is consent. And

consent is terrible. Most of the time this will work as advertised, but

then there times when you get a message from a friend while you are waiting

for the site to send the OTP. But you are trained to click through, so you

do and now some random website receives entirely the wrong message.

The API could be a different shape that doesn't require consent AND

doesn't impose constraints on the shape of the message. But it would

require the API to be a different shape.

—

You are receiving this because you were mentioned.

Reply to this email directly, view it on GitHub

<#152 (comment)>,

or unsubscribe

<https://github.com/notifications/unsubscribe-auth/AAFJL2TTYTG2NCR5TXJOUCLRXLONPANCNFSM4HIIIRAQ>

.

|

Without taking a position on this specification, it's definitely not Martin's job to read the Android API docs. Our expectation is that these specifications be reasonably self-contained so that a reader can understand the security issues without having to read a bunch of other documents. The kind of OS-specific document you suggest is specifically out of scope here because the objective here is interoperable specifications. |

|

You don't need to read the Android API documentations. The SMS format

convention alone deals with the observation raised (it presupposes that it

is unlikely that a human would construct it accidentally).

Nevertheless, a summary of the underlying Android APIs is also available at

the explainer and the security / privacy sections (on the phone, will get

you a link handy momentarily).

…On Fri, Jun 19, 2020, 4:54 AM ekr ***@***.***> wrote:

I'm assuming you read the Android API behavior (which doesn't hand out any

SMS from your contacts list) AND the SMS formatting convention (which is

designed to be something unlikely for humans to construct)?

Without taking a position on this specification, it's definitely not

Martin's job to read the Android API docs. Our expectation is that these

specifications be reasonably self-contained so that a reader can understand

the security issues without having to read a bunch of other documents. The

kind of OS-specific document you suggest is specifically out of scope here

because the objective here is interoperable specifications.

—

You are receiving this because you were mentioned.

Reply to this email directly, view it on GitHub

<#152 (comment)>,

or unsubscribe

<https://github.com/notifications/unsubscribe-auth/AAFJL2UNYON2LV5DSA7S3GDRXNGXJANCNFSM4HIIIRAQ>

.

|

Ok, back on a computer, so here it goes:

The point I'm trying to make is that regarding [1] and [2] there isn't anything in neither the API shape nor the underlying OS capabilities that made us opt into consent: it was the considerations around tracking described in the spec and the explainer above. [1]

[2]

|

|

My contention was that the shape of the API made it impossible to achieve the consent-free usage described in my earlier comment. That requires more than the API provides. If we were to provide this API, concerns about leaking private information would likely force us to use a consent dialog much like you have decided to do. I did not realize that messages from senders in contacts would not get passed through, which has some interesting effects, but that doesn't really change my analysis. Indeed, it suggests that if I happen to have the SMS sender in my address book, the API would not work, which isn't ideal. That might be addressed by having the page indicate where the SMS is supposed to come from, which might also make the risk of accidentally leaking private messages far less, but I expect that this would be operationally infeasible, especially relative to the added risk of abuse that comes with that sort of targeting. |

(Apologies for the drive-by here) Having the page specify the expected sender seems reasonable as an extra layer atop the origin-binding, but I don't know that it changes the calculus much. If we assume that 1) the UA is effective in filtering SMS messages to only those meeting the defined format, and 2) that same-origin works, then adding |

|

Still trying to understand your analysis here ... trying to put together some related observations, so apologies if these are coming from various sources ...

From what I gather from that thread, the important bits are here:

Which seems to boil down to:

But then later you make an observation:

Which I'm reading as "because of the privacy involved, we would have to have a consent dialog regardless, so this isn't tied to a different API formulation, but to privacy" which is where we arrived at too. Do I understand this correctly? Or are you suggesting that

That's by design. We expect SMSes to come from servers sending you one time passwords, not your friends. Can you expand on "which isn't ideal"?

Isn't the page itself calling the API enough indication that it is about to send an SMS to itself? |

I think the right analogy to be made here is the expected

If you open two tabs, with two different origins and they send two SMSes at the same time, how does the user agent know which SMS to send to which origin? |

I'm not EKR, but as a matter of practice, I choose to name (that is, add address book entries for) the source numbers that are used by various institutions to send SMS notifications, including short codes. (It's pretty meager protection, but I use this predominantly as a flag that allows me to scrutinize messages more closely if they come from a short code I haven't seen before.) As a user, I would be surprised if this defeated an otherwise functioning API; and, save for my involvement in this conversation, I would probably never figure out why something that works for most everyone else fails for me. |

Quite likely, yes. It would also obviate any need for origin-bound one-time codes, as the proof would not depend on special formatting. That is just one potential spelling of an API though. I'm not especially opinionated on whether this is spelt with form controls or something imperative like (FWIW, I do what Adam does too.)

I believe that JC was correct in identifying the sender. Yes, it is true that a malicious SMS sender can spoof their number (we'll have to wait and see how the robocalling edicts play out there), but the goal here is to distinguish between honest senders. Assuming that this is a site that is attempting to verify ownership of a number - leaving aside whether proof of receipt actually means something - then identifying their own sending number will avoid accidentally capturing messages sent by others. A site might claim that they own a different number (maybe a number of a friend, because some sites have that information), but then they really only gain something if a) the real owner of that number sends a message in the time afforded them, and b) the browser/OS passes that message to the site. Of course, requiring that a hash is provided largely stops this, though you might want to impose minimum entropy restrictions so that you don't capture messages that are easy to predict like "sure" or "ok" (for whatever value those have). Rate limiting the API might also be worth doing: if the goal is to demonstrate ownership of a phone number, sites don't need to do this more than once (maybe with a tiny allowance for the site losing state). However, as I said, specifying a sender doesn't seem likely to be operationally feasible. Most sites will have to outsource SMS sending capabilities, and those arrangements might make it difficult to know what number will be used. It's already something of an imposition to ask that they know the format of the message, but that seems at least tractable. |

|

Noticed last update is 2 years and 7 months ago, are there any updates on this? Thank you. |

Request for Mozilla Position on an Emerging Web Specification

This is something that Google folks are working on that it would be good if we had an opinion on.

The text was updated successfully, but these errors were encountered: